By Rachel Feintzeig

As suicide rates have climbed in recent years, so have instances

of employees ending their lives at the workplace.

It happened at a Bank of America Corp. call center in New Mexico

in November last year, a Ford Motor Co. plant outside Detroit in

October, and at Apple Inc.'s Cupertino, Calif., headquarters in

April 2016.

Nationwide, the numbers are small but striking. According to the

Bureau of Labor Statistics, suicides at workplaces totaled 291 in

2016, the most recent year of data and the highest number since the

government began tallying such events 25 years ago. U.S. suicides

overall totaled nearly 45,000 in that year, a 35% increase compared

with 10 years earlier, according to the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention's National Center for Health Statistics.

Sudden and traumatic for colleagues, the incidents can prompt

ripples of anger and guilt across an organization, potentially

damaging productivity.

Corporate managers are increasingly preparing for the

possibility. Employers are bringing in counselors to teach managers

to spot some of the potential warning signs: Someone planning

suicide might exhibit a sharp decline in personal hygiene or a

major change in personality. He or she might say things like, "The

world would be better off without me, " according to Larry Barton,

who advises Fortune 500 companies on workplace violence and crisis

management.

After a suicide, companies usually tap an employee-assistance

program to help traumatized colleagues, including those who may

have witnessed the event.

Experts and leaders say they aren't sure what is prompting the

uptick in workplace suicide. "If I knew, I'd be able to prevent

it," said Leon Lott, the sheriff for South Carolina's Richland

County, who lost one of his deputies to suicide in July.

"There's no such thing as a remedy," Mr. Barton said. He

received 47 calls related to suicide attempts at work in 2017, up

from 23 in 2016. "It's part of our work life," he said.

One possible factor in the uptick in the overall suicide rate is

that more suicides might be recorded as such now, compared with

earlier data that was often influenced by social pressure to deny

or cover up suicide as a cause of death.

At PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP in the UK, colleagues and

passersby witnessed as a 23-year-old accounting employee, Joshua

Jones, jumped from the firm's offices in a London building one

evening in August 2015. The company brought in counselors for two

weeks in an effort to calm employees, some of whom had been

bursting into tears during the workday, said Sarah Churchman, a PwC

human resources executive. Others stayed away from work for

days.

"Some people couldn't come into the office because they couldn't

get it out of their minds," Ms. Churchman said.

In the wake of the death, PwC helped employees share stories

about anxiety and depression with one another and created a mobile

app with information on mental-health resources.

The company is aiming this year to train some 5,000 managers in

signs that a co-worker is at risk and how to approach them about

getting help.

Mr. Barton said clients used to push back on including the topic

of suicide in employee training. A common response, he said, was,

"Do we really have to talk about this?" Now, many clients request

the training.

Mr. Barton said distressed employees who don't care much about

their jobs might choose to commit suicide at work because they

won't have to worry about loved ones finding the body. On the other

hand, workers consumed with their work also might end their lives

while on the job, perhaps in an attempt to send a message.

In November 2016, an Amazon employee jumped from a building on

the company's Seattle campus. He claimed he had been put on a

performance-improvement plan and sent an email to CEO Jeff Bezos

and colleagues criticizing the company. He survived the fall.

Colleagues were upset by the incident and talked about it in

hushed tones, said Adam Park, an Amazon software engineer who was

working at the building next to the one where the attempt took

place.

Employees received a note about mental-health issues and

counseling services, Mr. Park said. The event was a reminder that

Amazon is a high-stress place to work, he said. "It made me double

down on my resolve to do well at my job so I wouldn't end up in a

situation like that," he said, referring to performance-improvement

plans.

A spokesman for Amazon declined to comment on the incident.

Bank of America closed its Rio Rancho, N.M., call center for a

week in November, after an employee shot and killed himself in a

break room, Lori Henkel, a human-resources executive who leads

life-event services, said.

Employees had evacuated the building during a standoff with law

enforcement officials, who were trying to prevent the suicide,

according to a Bank of America spokesman. Afterward, workers waited

in the parking lot while security personnel guided managers through

the building to retrieve personal belongings, shielding them from

the aftermath. Bank executives traveled to New Mexico and met with

managers, workers and counselors at a local hotel.

Employees requested that the company repurpose the space where

the incident occurred. "Right now it's just an extra room in the

front of the call center," Ms. Henkel said.

Jobs where people have access to a means of ending life can

heighten the risk, experts say. Sheriff Lott's deputy, Derek Fish,

shot himself with his service weapon in a patrol car while parked

at one of the department's regional headquarters.

The Richland County Sheriff's Department this month started

suicide-prevention training for employees. The department has a

counselor on staff and mandatory post-traumatic stress syndrome

training.

Sheriff Lott -- who has experienced four employee suicides since

taking his job some two decades ago -- said he feels like a failure

every time. This time, he said, he made sure to talk about the

tragedy publicly. "The worst thing you can do is ignore it," he

said.

Write to Rachel Feintzeig at rachel.feintzeig@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 17, 2018 11:33 ET (16:33 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

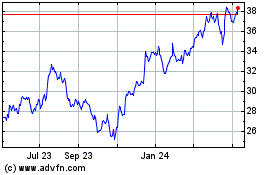

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

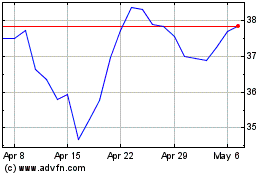

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024