By Michael C. Bender

Former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson and national economic

adviser Gary Cohn are just the latest corporate chieftains to

stumble in the transition from the autonomous confines of the

corner suite to the political pressure cooker in Washington.

It is easy to see why a cabinet post or White House position --

the frequent landing spot in Washington for senior executives --

appeals to those who have spent a career climbing to the top of the

corporate ladder.

Top executives, like politicians, must consider a myriad of

constituencies -- shareholders, workers, unions, board members,

customers -- and the best ones accommodate them all.

But the comparisons can be misleading and the success stories

are outstripped by those who have struggled, according to business

lobbyists and political strategists.

In just the past week, both Mr. Cohn, the former president of

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. , and Mr. Tillerson, who headed Exxon

Mobil Corp., ended their service in the White House in part because

they disagreed with actions taken by their new boss: President

Donald Trump.

Mr. Cohn objected to the White House decision to impose tariffs;

Mr. Tillerson differed with the president on the Iran nuclear deal

and other matters.

"The truth is they are very different environments," Mike

Feldman, a former adviser to then-Vice President Al Gore who now

provides corporate consulting, said about the transition from

business to politics.

Those who did make a broadly favorable impression, such as

former Treasury Secretary Robert Rubin, said they arrived in

Washington aware of what they don't know, not what they do

know.

After President Bill Clinton invited the co-chairman of Goldman

Sachs to join the administration in 1993, Mr. Rubin carried a

yellow legal pad, which he still has, around the nation's capital

seeking advice from veteran politicians.

"Some people who go from the corporate structure operate on the

assumption that they've had success in business and can do the same

in government," Mr. Rubin said. "But Washington is just a different

world."

One common pitfall is an impulse to rely on what worked in the

past.

Former Treasury Secretary Paul O'Neill, who was tapped by

President George W. Bush, had focused heavily on workplace safety

as chairman and chief executive at Alcoa Corp., the

Pittsburgh-based industrial giant.

When he arrived in Washington in 2001, he met Larry Summers, the

departing Treasury boss, for breakfast at the J.W. Marriott to

discuss the new job, including the issue of workplace safety at

Treasury. Mr. O'Neill recalled that Mr. Summers turned to his chief

of staff, Sheryl Sandberg, the current chief operating officer of

Facebook Inc., and asked if she knew what Mr. O'Neill was talking

about.

"Larry Summers was sitting on top of a workforce population of

125,000, and he didn't have a clue about workplace safety -- not a

clue," Mr. O'Neill said in an interview.

In the noisy, hot aluminum plants where workers wield vibrating

hand tools and can be exposed to ultraviolet radiation, safety is

paramount. But at Treasury, Mr. O'Neill's initiative became a

running joke as workers teased that their biggest risk was paper

cuts, said Charles Duhigg, an author who wrote about Mr. O'Neill in

his book, "The Power of Habit."

"At Alcoa, he was lioned for his focus on safety," Mr. Duhigg

said. "At Treasury, it didn't really matter."

Mr. O'Neill was forced out of the Bush administration in 2002

after repeated battles with the West Wing over increasing budget

deficits. One takeaway from his government service that he still

prides: The number of workplace injuries at the agency

significantly dropped under his watch.

CEOs must be adept at navigating internal politics. But in

Washington, victories are often claimed in the face of what would

otherwise look like defeats.

Veterans Affairs Secretary Bob McDonald stepped away as chief

executive of Procter & Gamble Co. in 2014 to take over an

agency in crisis.

The longtime Republican joined President Barack Obama's

administration, with a mission to improve access to the nation's

largest health-care system. His progress has been hailed by

health-care officials, military advocates and Harvard Business

School.

But years later what is still gnawing at him is the legislation

that failed because, in his view, Republicans wanted the bill to

pass under a different president.

"The biggest frustration is the politics," Mr. McDonald said

about his time in office. "It gets in the way of doing what's right

for the people. The idea that there is an opposition party? You

have people behaving counter to what you're trying to do, even

though they know it's going to hurt veterans."

In an act of quiet rebellion, Mr. McDonald said he dropped his

party affiliation when he left Washington. Now semiretired in

Florida, he is a registered independent.

In the business world, executives have often been groomed for

succession, and know their companies extremely well.

"One thing I can tell you, unequivocally, is that there were no

surprises with Rex," said William Howell, whose two decades on the

Exxon board included the 2006 election of Mr. Tillerson as the

company's chairman and chief executive. "Exxon has one of the most

intense internal management processes I have every viewed in

corporate America," he said.

Being installed atop an established agency like the State

Department -- with a budget of $55 billion (about one-fourth of

Exxon's) and a range of staff that includes the foreign service,

career staff in Washington and dozens of political appointees --

presents a sharp learning curve that must be mastered in a very

short amount of time.

For Mr. Tillerson, time ran out on Tuesday when he learned he

had been fired by way of a presidential tweet.

"If you want to get anything done, you have to have people

around you who know how the levers work," said Mike Leavitt, chief

executive of a regional insurance company before becoming governor

of Utah in 1993. He later served as Environmental Protection Agency

administrator and secretary of Health and Human Services under

George W. Bush.

"It was a profound epiphany for me when I realized that if you

come into government without understanding how it works -- its

limitations and its strengths -- you can be confounded in many

different ways," Mr. Leavitt said.

Write to Michael C. Bender at Mike.Bender@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 14, 2018 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

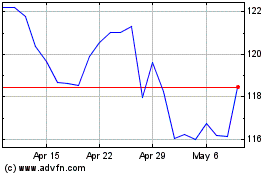

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

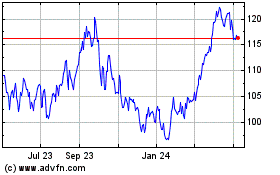

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024