How Stock Creates Bonds: The Starbucks Job Incentive -- WSJ

July 21 2018 - 3:02AM

Dow Jones News

By John D. Stoll

This article is being republished as part of our daily

reproduction of WSJ.com articles that also appeared in the U.S.

print edition of The Wall Street Journal (July 21, 2018).

U.S. companies are collecting record amounts of cash in their

coffers, and many can't think of anything better to do with it than

buy back their stock. Here's a better idea: Hand out some of those

shares to rank-and-file employees.

Starbucks Corp. has been awarding shares to baristas since the

1990s. The company says it has granted more than $1 billion in

equity under its "Bean Stock" program. It currently offers

restricted stock vesting over two years to nearly all

employees.

Apple Inc. in 2015 initiated a restricted-stock program that

includes grants to retail employees. A worker getting $1,000 in

Apple stock at that time would have seen the investment grow to

more than $1,800 as of this week, including dividends.

But Apple and Starbucks are exceptions in a corporate

environment where most of the equity compensation is reserved for

white-collar professionals, executives or higher-level managers.

Companies, however, have plenty of cushion to reconsider this

equation.

Nonfinancial businesses had amassed $2.1 trillion in cash and

liquid investments by the end of last year, according to S&P

Global Ratings. S&P 500 companies are on track to buy back $800

billion in shares this year, a move designed to make the remaining

shares -- the ones that aren't repurchased -- more valuable, since

each share now represents a larger piece of the company.

In practice, though, a sizable portion of the repurchased shares

are reissued in the form of equity-based compensation, said Jesse

Fried, a Harvard Law School professor who studies compensation and

buybacks.

Mr. Fried said shareholders may see aligning executive pay with

stock performance as logical because senior leaders can do

disproportionately more to affect a company's performance. But

giving out shares at the entry level where wages are set could be

considered a handout. "Companies aren't in the business of making

charitable contributions with other people's money," he said.

Still, there is evidence that offering lower-level workers a

modest amount of restricted stock is good for the bottom line

because it generates loyalty. With the U.S. unemployment rate

hitting a five-decade low this year, attracting and retaining

workers has become a major challenge for many companies.

Consider Shannon Rainey's story. The 34-year-old has worked his

way up at Starbucks since joining as a part-timer in the summer of

2003. He's been collecting company shares under the Bean Stock plan

and cashed in at various times. He used some of the proceeds to

remodel a house, and is now selling stock to construct a nursery in

his home as his family grows.

"I've gotten pretty lucky over the past ten years," Mr. Rainey

said, referring to the strong run for Starbucks' shares. Now a

store manager in Seattle, he tells potential employees about the

stock program as a way to get them to hire on, and uses it to

motivate workers in their early days on the job. His contact

information was provided to me by a company spokesman.

Many companies take a different route, offering a cash bonus or

profit-sharing that typically come with no strings. Some suggest

the workaday crowd doesn't want stock because of its volatility and

potential to create overexposure to an employer's performance.

"Cash is king for rank-and-file or hourly folks," Stephanie

Penner, a senior partner with human-resources consulting firm

Mercer LLC, said. "They're definitely going to be more interested

in what their hourly rate is."

Ms. Penner, however, said that there is an appetite among all

employees to get equal treatment as top executives even if they

aren't getting wealthy. Apple's decision to pass out a modest

amount of restricted stock is an example.

"It isn't the actual value of the stock that matters, it's the

symbolic value of that stock," Ms. Penner said. "This is a powerful

recipe for an engaged workplace."

Apple earlier this year awarded $2,500 restricted-stock grants

to employees following the passage of the Trump administration's

tax cuts. It has also repurchased $200 billion of its stock since

2012, and its board authorized another $100 billion buyback program

just before the company released second-quarter results in May.

Meanwhile, Apple's market capitalization is approaching a $1

trillion milestone that no U.S. company has ever reached.

A recent study by the National Center for Employee Ownership

that an index of 28 companies offering "broad-based" equity options

-- including stock for retirement plans and grants -- outperformed

the S&P 500 by nearly a two-to-one margin over the past

year.

The NCEO, a non-profit based in Oakland, Calif., estimates

workers who make less than $30,000 and get equity in their company

have 11% longer median job tenures than those without.

Ms. Penner said restricted stock grants are part of a broader

move by companies to improve their benefits to help with retention.

Longer parental leaves, richer medical-benefit packages and

education reimbursement are becoming more widely available.

These perks are to human-resources departments what the spice

rack is to a chef: "If you go to cook a chicken and you cook the

chicken without spices it's going to be kind of bland," she said.

"Add the right ingredients and you'll get better results."

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 21, 2018 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

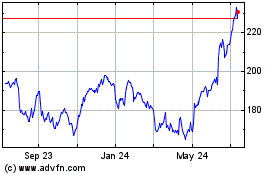

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

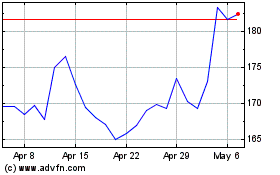

Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024