By Liz Hoffman

NEW YORK -- Lloyd Blankfein secured the survival of Goldman

Sachs Group Inc. by leading it through the financial crisis. The

challenge for its next leader: how to thrive in a radically altered

postcrisis world.

The bank on Tuesday said David M. Solomon, Goldman's president

and chief operating officer, will take over as chief executive from

Mr. Blankfein. The move puts a symbolic cap on Goldman's postcrisis

era and will fuel the firm's continued evolution from a secretive

trading powerhouse into a more nimble and entrepreneurial

place.

In formally choosing Mr. Solomon, 56 years old, Goldman is

tapping a proven business-builder who has spoken forcefully about

the need for the firm to be less stuck in its ways. Neither a

sharp-elbowed trader nor genteel banker in the classic mold -- he

moonlights as a dance-club DJ -- he came to Goldman as a rare

outside partner in 1999 and has spent nearly his entire career

there in management jobs.

He has already been sketching out an agenda that would push the

firm to be more organized, decisive and open. Insiders expect him

to impose a corporate discipline that Goldman, which spent decades

as a loosely run partnership, has been slow to embrace. One of his

first moves, according to people familiar with the matter, is to

demand three-year operating budgets from Goldman's division

heads.

He has tipped to close associates that he is likely to prune

Goldman's storied management committee, whose membership has

swelled in the past decade, and refocus power among executives who

run businesses. He has built a strategy team to scout new business

ideas and acquisitions; pushed to include more women in the firm's

senior ranks; and is considering an investor day for 2019, lifting

the secrecy that once bolstered Goldman's mythic status but has

worn thin as profits shrank.

"Everything's on the table," Mr. Solomon has lately told top

executives.

Mr. Solomon became the heir apparent earlier this year, winning

a 15-month audition that pitted him against co-president Harvey

Schwartz, who resigned in March when the outcome became clear.

Tuesday's announcement formalizes that arrangement, setting Mr.

Solomon up to take control when Mr. Blankfein departs Sept. 30.

Under Mr. Blankfein, Goldman came to dominate Wall Street with a

mix of trading prowess and political clout. But it has struggled in

the world created by the financial crisis and is reaching to

unfamiliar areas such as consumer and commercial banking to replace

billions of dollars of trading profits that are unlikely to

return.

A combination of calm markets, tough regulation and changing

client behavior has wreaked havoc on securities desks across Wall

Street, hitting trading-heavy Goldman the hardest.

Its fixed-income division, which buys and sells corporate bonds,

oil, interest-rate swaps, among other things, once churned out $1

billion every 10 days or so. Last year, that took them an average

of 10 weeks.

In search of new profits, Goldman is making a belated push into

consumer banking and corporate cash management, hoping to challenge

Main Street giants such as JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Citigroup

Inc. on their turf. The firm aims to add $5 billion in annual

revenue by 2020 and is under pressure to show it can build new

business and hit targets.

In a first for Goldman, its succession saga has played out in

public view. It was a quick and undramatic transition when Mr.

Blankfein took over in 2006 from Henry M. Paulson Jr., who was

tapped as the Bush administration's Treasury secretary. Goldman was

still a private company when Mr. Paulson wrested control from Jon

Corzine in 1999. And for much of its history, power rested with its

partnership rather than a sole leader.

This time, Mr. Blankfein, 63, and the 56-year-old Mr. Solomon

have been working from neighboring glass-walled offices on the 41st

floor of Goldman's New York headquarters. Mr. Blankfein, who has

joked in the past that he intended to die at his desk, has seemed

at times ambivalent about handing over the reins.

At a meeting this spring of the firm's management committee, Mr.

Blankfein addressed news articles, including a March report in The

Wall Street Journal, that said he planned to step down later this

year.

"We're just going to have to deal with it for a little while,"

he said of the media attention, according to people briefed on his

remarks. Then the CEO addressed Mr. Solomon, who was dialing in

from Saudi Arabia, quipping: "But meanwhile, David, maybe you

should just stay over there."

Mr. Solomon came to Wall Street in the mid-1980s and spent his

early years in the mercenary world of junk debt. He played social

planner to a group of college friends, organizing ski trips to

Vermont and summer rentals in the Hamptons, where roommates would

wake up to find him mowing the lawn.

After stints at Salomon Brothers and Bear Stearns, he joined

Goldman as a partner -- it is unusual for an outsider to join at

that rank -- and set about building a junk-bond business. He then

ran its investment-banking division for a decade, turning it from a

loose collection of fiefs into a professionalized force that is the

largest on Wall Street by revenue.

Mr. Solomon had a strict policy of giving zero bonuses to the

bottom 5% of employees and aggressively clawed back stock from

bankers who left Goldman to start their own firms. He helped build

a corporate lending and debt-underwriting business -- a risky area

that Goldman, notoriously tightfisted on loans, had avoided in the

past -- that generated record revenues last year.

In 2012, he took over the planning of a West Coast conference

aimed at entrepreneurs that Goldman hoped could strengthen its ties

to promising startups.

Will McDonough, then a Goldman vice president, described an

early planning call. "David swoops in such as a general, barking

orders, assigning responsibilities," said Mr. McDonough, who is now

CEO of a blockchain business. "He saw the idea had legs and brought

this intense discipline to it. I remember being taken aback, but it

worked."

Today the Builders + Innovators Summit is a must-attend for

startup founders and venture capitalists and has become a

significant feeder for Goldman's investment-banking business.

Off duty, Mr. Solomon skis Aspen bowls and kite-surfs and spins

records in Baker's Bay, the Bahamas enclave where he has a home.

Under the stage name D-Sol, he recently released his first single,

a remix of the Fleetwood Mac song "Don't Stop," on the streaming

service Spotify. His third New York restaurant, Legacy Records,

recently opened on Manhattan's West side.

"A perpetual motion machine," said longtime friend and Hilton

Worldwide Holdings Inc. Chief Executive Christopher Nassetta.

Mr. Blankfein leaves Goldman on firmer footing than he found it,

though it took a near-death experience to get there. Goldman was at

the forefront of the derivatives-trading boom that sowed the seeds

of the financial crisis, and emerged browbeaten but intact, having

avoided the billion-dollar losses that hit rivals. Its relative

fortunes earned it a political lashing and cast Mr. Blankfein as a

central villain of the meltdown, an image he spent years trying to

shed.

He grew a beard and joined Twitter. Goldman has spent millions

of dollars sponsoring female entrepreneurs and small businesses, in

part aiming to rehabilitate its image and gain goodwill in

Washington. Earlier this year, it began streaming conversations

between its executives and celebrities and business leaders

including General Motors Co. Chief Executive Mary Barra and soccer

star David Beckham on Hulu.

Mr. Solomon wasn't the obvious choice to succeed Mr. Blankfein.

Goldman insiders gave the edge to Mr. Schwartz, who had followed in

Mr. Blankfein's footsteps through the firm's trading arm and spent

four years as its chief financial officer, learning the businesses

and dealing with investors and regulators. Throughout much of the

15 months they competed for the top job, Mr. Solomon told

associates he believed the job was Mr. Schwartz's to lose.

Mr. Solomon had previously considered leaving Goldman, but

turned down a chance to run Sheldon Adelson's casino empire in

2014, and later pursued a top job at private-equity firm TPG.

His patience paid off with one of the most coveted jobs in

finance. Despite Goldman's challenges, it remains a powerful symbol

on Wall Street, and the men who have run it -- the firm has never

had a female CEO -- are often looked to as a senior voice in the

industry.

Mr. Solomon has wasted no time rethinking some of the firm's

oldest traditions.

Big companies including JPMorgan and Walmart Inc. hold annual

"investor days," where shareholders and analysts get updates and

meet with executives. Goldman never has. Mr. Solomon has asked

executives to plan one, possibly as soon as next year, people

familiar with the matter said.

Goldman's division heads typically prepare annual budgets. Mr.

Solomon wants three years of revenue and cost projections, hiring

plans and client coverage initiatives, according to people familiar

with the matter.

He is also discussing changes to Goldman's powerful management

committee, according to people briefed on the matter. The group

meets weekly on Monday mornings and is a carry-over from Goldman's

days as a private firm, when a small group of partners set firm

strategy.

Over the past decade it has swelled from fewer than a dozen

executives, each running a major business line, to more than 30.

About one-third of its members don't oversee a revenue-producing

unit or region, and critics say Mr. Blankfein has used committee

seats more to soothe egos and send signals to underlings and

regulators than to run the firm's day-to-day affairs.

A Goldman spokesman declined to make Mr. Blankfein available for

comment.

Mr. Solomon has discussed paring the committee or creating a

smaller group of top managers that would meet separately, people

familiar with the matter said. Executives from nonrevenue divisions

such as human resources and legal might be shifted to a broader,

less-powerful operating committee.

That would echo a move Mr. Solomon made while running the

investment-banking division. Frustrated its leadership was too big

and lumbering, he created a smaller brain trust of top executives,

a move that bruised some egos but sped up decision-making.

And as discussions get under way about the selection of the 2018

partner class, Mr. Solomon has advocated for a smaller one --

almost certainly under 100 -- with a higher allotment of bankers,

traders and other revenue-generating employees and fewer slots for

functions including compliance and operations, according to people

familiar with the discussions.

Mr. Solomon has taken up diversity as an issue, particularly the

lack of women in senior roles at Goldman. The incoming class of

college graduates that will join Goldman this fall is 48% women,

and the firm has set a goal of parity by 2021.

He urged the promotion of Beth Hammack to become Goldman's

treasurer last fall over the objections of Mr. Blankfein, who felt

Ms. Hammack was more valuable on the trading floor, where she was

one of just a handful of senior women, according to people familiar

with the matter. Mr. Solomon argued her promotion would send a

message that Goldman was serious about closing the gender gap in

its upper ranks, the people said.

"We're at a point in time where 'enough already,' " he told

PayPal CEO Dan Schulman in a video chat last month. "I have trouble

talking to my daughters about this and explaining why, for so long,

we haven't made more progress on this front."

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

July 17, 2018 10:38 ET (14:38 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

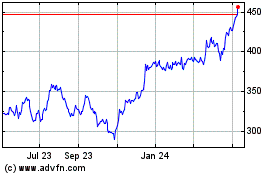

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

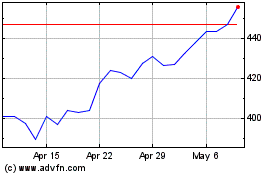

Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024