GE Shows What Happens When Dividend Investing Goes Wrong

November 01 2018 - 2:39PM

Dow Jones News

By James Mackintosh

If you invested in General Electric for the dividend, you

discovered your mistake on Tuesday when the payout was slashed from

12 cents to 1 cent a share each quarter. You were in good company

in your error: Investors focus far too much on dividends,

distorting corporate behavior and making it easy to forget that

what matters isn't the payout, but whether the business can sustain

it.

GE cut the dividend because it needs to hoard cash as it

restructures and shrinks. Yet, even the token penny payout is a

sign of the distortions the demand for dividends creates. The

decision to maintain it is clearly down to the excessive value

shareholders place on dividends.

There were plenty of warning signs that the dividend was

unaffordable. Dividends are a way to return profits to

shareholders, but GE's net income has been higher than the dividend

cost in only four of the past 15 quarters -- compared with all but

two quarters in the entire period from 1989 to Lehman's failure in

2008.

Even excluding this week's monster $22.8 billion loss, GE has

paid out almost twice as much in dividends since 2012 as it made in

net income. Every shareholder should have realized that the

dividend was getting riskier, even if they weren't looking at the

falling amount of cash the business was producing.

In parallel, GE slashed its capital spending from $15 billion in

2012 to about $8 billion over the past 12 months, taking it back to

where it stood in 1998 -- before inflation. The business has been

eating its seed corn recently, partly to maintain the dividend.

Dividends do, of course, matter. The prospect of eventual future

dividends is the main reason shares have any value at all. Their

reinvestment has accounted for the bulk of long-term returns on

stocks. Better still, dividends can instill discipline on

executives, preventing them from indulging their wildest flights of

fancy by reminding them that they have to generate the cash to pay

stockholders. Chief executives given a free rein and plenty of

money have an unfortunate tendency to engage in value-destroying

takeovers, build fancy new headquarters and diversify into trendy

new businesses about which they know little. Better to pay

dividends or buy back shares than fritter the money away.

However, dividends should be the result of a successful business

throwing off cash, not something that executives strive to maintain

even when the cash could better be used elsewhere. GE is a classic

case of the dividend being prioritized in the hope that something

comes up.

For the major oil companies, something did come up, making it

look as though steady dividends could be justified. Consider Royal

Dutch Shell, the Anglo-Dutch oil company that is among the world's

most reliable dividend payers. It resorted to borrowing to pay its

dividend in 2015 and 2016 as it was hammered by the oil-price

slump, with earnings below the cost of the dividend for six

quarters in a row.

To save cash Shell offered investors the option to take their

dividend in the form of new shares, and like GE it and other oil

companies took an ax to capital spending. Unlike GE, Shell was

rescued by the oil-price recovery, and is now generating enough

cash both to pay the dividend and to buy back the shares it

issued.

Shareholders like the regular Shell dividend, and can argue that

Shell was right to keep paying it, since it all worked out OK. But

even here it would have been less risky for the company and its

long-term value had it scrapped the dividend when trouble hit, and

borrowed less. Investors who need cash should sell some of their

shares (for some of the smallest investors trading costs might be a

bar, but at $10 a trade this is irrelevant for most). Instead,

their irrational attachment to steady payments pushes companies to

borrow and to cut back the business in bad times to maintain the

payment.

Those eagerly anticipating their next dividend check might be

spluttering into their latte in horror at these views. But whether

the dividend is paid out or not should make no difference to them.

Shareholders own the company. When it pays out money to

shareholders, it is worth less -- by precisely the amount of the

dividend. The shareholder's pocketbook is unchanged. Somehow

investors still fail to notice this.

In an ideal world, companies would pay out cash when they have

no good uses for it, and invest it in new projects only when

justified by expected future profits. In an ideal world,

shareholders would trust the board's judgment, and executives

wouldn't be swayed by the latest fashions. In reality shareholders

swing from encouraging massive overinvestment to demanding all cash

be returned (now!) while managers frequently ignore solid projects

to game some ratio currently in vogue with Wall Street, or set out

on empire-building projects to boost their egos.

Demanding a solid dividend has merit as a way to limit

empire-building, but investors should beware companies that make it

a target to be met at all costs. Shareholders need to keep an eye

on much more than the quarterly payout to avoid their investments

going the way of GE.

Write to James Mackintosh at James.Mackintosh@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 01, 2018 14:24 ET (18:24 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

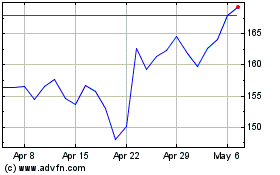

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

GE Aerospace (NYSE:GE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024