By Andrew Tangel

President Donald Trump's plan to impose steep tariffs on steel

and aluminum imports drew sharp criticism Thursday from industries

that fear it could raise their costs to make everything from

airplanes to beer cans.

The bigger worry, some manufacturers and agricultural groups

said, is the potential for retaliatory measures by other countries

that could imperil U.S. exports and jobs.

Mr. Trump said his plan to impose tariffs of 25% on imported

steel and 10% on imported aluminum is needed to address what he

described as a trade imbalance benefiting other countries.

Companies that make steel and aluminum in the U.S. have in recent

years lobbied for the tariffs, which they say are needed to compete

with foreign competitors making metal at lower prices.

"We appreciate the President's commitment to strengthening the

U.S. aluminum industry," the Aluminum Association trade group said

Thursday.

It wasn't immediately clear what types of aluminum and steel

would be subject to new tariffs.

The impact on metals-consuming industries will also hinge on

whether the administration grants exemptions to some exporting

nations.

Some industries are already lining up for those exemptions. The

Beer Institute, a trade group, called for "cansheet" aluminum to be

excluded from any new trade barriers. "Imported aluminum used to

make beer cans is not a threat to national security," said Jim

McGreevy, the group's president.

Mr. Trump invoked national-security concerns as a reason behind

the administration's push for tariffs. Studies conducted by the

Commerce Department, made public last month, concluded metals

imports had eroded the country's ability to make its own weapons,

tanks and aircraft as well as other critical infrastructure.

Manufacturers in the defense industry rely on imports for only a

fraction of their steel and aluminum needs, and the Defense

Department said last week it wasn't concerned about the effect of

tariffs on the industrial base for military equipment.

But Remy Nathan, vice president for international affairs at the

Aerospace Industries Association, said higher costs and retaliatory

measures could disrupt global supply chains and hit exports,

denting the aerospace and defense industries' $86 billion trade

surplus last year. The group represents companies including Boeing

Co. and Lockheed Martin Corp.

"It's the indirect industrial impact we are most concerned

about," said Mr. Nathan.

Manufacturers and trade groups for some of the country's biggest

metals' consumers expressed opposition to the planned tariffs,

saying the trade barriers would increase their costs -- expenses

that may be passed along to consumers.

"It's going to be expensive," said Ed Bolas, chief financial

officer at DyCast Specialties Corp., a maker of parts for products

including cutting tools and engines. "All of it will impact the

consumer."

The Association of Equipment Manufacturers, which represents

heavy machinery giants Caterpillar Inc. and Deere & Co., said

new trade barriers will hurt American exports. Caterpillar

executives have said tariffs could drive up prices for domestic

steel and make it costlier for it to produce mining trucks,

bulldozers and other equipment.

Steel is the largest input cost for big machinery producers,

accounting for around 65% of raw material expenses at Caterpillar,

with aluminum adding another 10%, according to JPMorgan analyst Ann

Duignan. She estimates agricultural equipment makers such as Deere

are even more exposed to raw material inflation, unless they can

claw back costs through higher sale prices.

Polaris Industries Inc., which buys more than $300 million in

steel and aluminum each year to make off-road vehicles, snowmobiles

and motorcycles, doesn't expect tariffs to significantly increase

its costs, Chief Executive Scott Wine said Thursday.

But Mr. Wine said he was concerned that duties or retaliatory

trade barriers would lead other manufacturers or agricultural

companies to lay off workers that buy his company's products.

"President Trump has been a phenomenal supporter of jobs in the

U.S., and this would not be in line with his previous efforts," he

said.

A lack of clarity on how or whether the Trump administration

would impose tariffs has been frustrating, said Mr. Bolas, of

DyCast Specialties. The Starbuck, Minn.-based company has put off a

5% raise for its 58 employees this year because of the uncertainty

over how tariffs would affect its costs, he said.

Some auto makers and parts suppliers reacted to Thursday's

announcement with alarm. The Motor Equipment Manufacturers

Association, the chief automotive components supplier trade group,

said the new tariffs would endanger jobs and raise costs.

A lobby representing foreign auto and parts makers in the U.S.

also criticized the move and linked it to a broader White House

agenda of "risky renegotiations" for Nafta and other trade deals.

"The Administration's decision to impose substantial steel and

aluminum tariffs will harm the U.S. auto industry," John Bozzella,

CEO of the Association of Global Automakers, said in a

statement.

Not all auto makers signaled immediate opposition to the

announcement. General Motors Co., which buys 90% of its steel from

U.S. suppliers, said in a statement that it was reviewing the

details but "support[s] trade policies that enable U.S.

manufacturers to win and grow jobs in the U.S., and at the same

time succeed in global markets."

Meanwhile, farm groups feared Mr. Trump's move would invite

retaliation against U.S. crop exports, after China recently raised

the prospect of tariffs on sorghum, a grain used in livestock

feed.

"These [steel and aluminum] tariffs are very likely to

accelerate a tit-for-tat approach on trade, putting U.S.

agricultural exports in the crosshairs," said Brian Kuehl,

executive director of Farmers for Free Trade, a Montana-based group

set up to defend U.S. agricultural exports.

The farm group said a U.S.-Mexico dispute over trucking rules in

the late 1990s led Mexico to place tariffs on U.S. apples, cheese

and wine, while China placed a steep duty on chicken parts imported

from the U.S. after tariffs in 2009 were placed onto Chinese tire

imports.

"The agriculture sector knows from experience that our ag

exports are the first to be hit by retaliation," Mr. Kuehl

said.

--Doug Cameron, Jacob Bunge and Chester Dawson contributed to

this article.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 01, 2018 17:17 ET (22:17 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

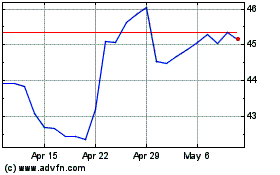

General Motors (NYSE:GM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

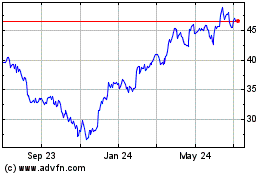

General Motors (NYSE:GM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024