Employers Struggle To Make a Dent in Health Costs

February 01 2018 - 12:02PM

Dow Jones News

By Anna Wilde Mathews and Joseph Walker

The planned venture by Amazon.com Inc., Berkshire Hathaway Inc.

and JPMorgan Chase & Co. to overhaul their workers' health care

follows years of similar efforts by employers to change a complex

and entrenched industry, with mixed success.

The three big companies shook up health-care firms' shares

Tuesday by saying they will form a not-for-profit company to reduce

costs and improve the health-care experience of hundreds of

thousands of U.S. employees. People with knowledge of the matter

said nothing had been decided beyond creating the new company, but

worries about the potential threat pushed down shares of insurers

and pharmacy benefit managers.

Yet even with its high-profile backers, the project will face

many of the same barriers as did previous employer efforts to come

together to reform the giant U.S. health-care sector, which

represents about 17.9% of the gross domestic product.

"This is not a new idea," said Lonny Reisman, a former executive

at Aetna Inc. who helped create an employer coalition in the 1990s

that crafted deals with health-maintenance organizations. Do

employer groups "have enough clout to actually change the nature of

health-care delivery and pricing?" he said. "I don't think they've

been very successful."

Earlier employer alliances have mostly been able to point to

incremental gains, such as cheaper pharmacy-benefit rates for

members or improvements in public quality measures of health-care

providers and health insurers. They haven't managed "in a wholesale

way to transform an industry, which is what these guys are trying

to do," said Jim Winkler, a senior vice president at consulting

firm Aon PLC. "It is really hard to do."

The Health Transformation Alliance, founded in 2016, is perhaps

the highest-profile existing employer effort, with 46 members

including American Express Co., Johnson & Johnson and Macy's

Inc. -- as well as JPMorgan and Berkshire's BNSF Railway Co.

A JPMorgan spokesman said the bank, after joining weeks ago,

hasn't yet joined any of the alliance's initiatives. A BNSF

spokesman didn't respond to a request for comment.

The alliance this year began contracting with two

pharmacy-benefit managers, or PBMs, to provide lower prices and

more transparency on fees and rebates. This year, 21 companies are

participating in the contracts, and four more are slated to join

next year, alliance CEO Robert Andrews said in an interview. The

PBM contracts will save the 21 current participants at least $600

million over three years compared with their previous deals, he

estimated.

The alliance is also contracting with health-care providers in

certain markets to care for employees with diabetes, hip and knee

replacements and lower back pain. The contracts are supposed to pay

doctors based on how well they meet targets such as quick recovery

times.

In June, the alliance began an effort to meld member companies'

health-claims data into International Business Machines Corp.'s

Watson software.

It may take more radical steps in the future, such as forming

its own PBM if its current pharmacy-benefits contracts don't meet

its goals. "Who can deliver that is still an open question, whether

it's our own PBM or another existing organization," Mr. Andrews

said. "We're looking at every option on the table."

Many large employers have joined purchasing coalitions focused

on pharmacy benefits, some formed by big consultants such as Aon

and Willis Towers Watson. These coalitions typically negotiate

deals with PBMs on behalf of their members. The members get "better

pricing and a packaged set of services," said Julie Stone, a

practice leader at Willis Towers Watson, due partly to "the size

the coalition has grown to and the leverage" it generates with

suppliers.

One challenge for employers seeking to make large-scale changes

is that health-care markets are fractured and vary widely by

market. Even large national employers often have limited

populations in a particular location.

"You need critical mass locally to leverage a pricing

advantage," said Brian Marcotte, chief executive of the National

Business Group on Health, which offers advice and research for

employers but doesn't seek to purchase services for its members.

"You still need the delivery system to provide the care."

Health-care vendors can fight back against employers'

cooperative work. An employer group, the Pharmaceutical Coalition,

in 2015 dissolved a drug-pricing transparency initiative after PBMs

started requiring the employers to sign "very tight nondisclosure

agreements," said Amanda H. Beck, a spokeswoman for the HR Policy

Association, an umbrella group that spearheaded the coalition. The

group's members, which included Caterpillar Inc., had aimed to

create stricter standards for pharmacy-benefit contracting, such as

sharing all discounts and rebates with coalition members.

Employers themselves also may struggle to unite, because they

often have far different cultures, employee populations and

geographies. "Employers have a very hard time coming to agreement

on the exact same contract terms," said Suzanne Delbanco, executive

director of Catalyst for Payment Reform, which is backed by

employers but doesn't negotiate contracts on their behalf. She says

her group has helped increase transparency on health-care prices

and move insurers toward new methods of paying health-care

providers.

--Emily Glazer and Nicole Friedman contributed to this

article.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 01, 2018 11:47 ET (16:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

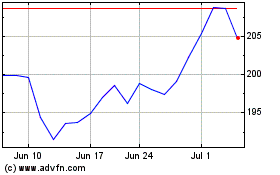

JP Morgan Chase (NYSE:JPM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

JP Morgan Chase (NYSE:JPM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024