Banks' Golden Deposits Are Heading Out the Door

October 22 2018 - 5:59AM

Dow Jones News

By Rachel Louise Ensign

There's less free money to go around for banks.

After nearly three years of rate increases from the Federal

Reserve, customers are pulling billions of dollars out of accounts

that don't earn interest and putting their money into

higher-yielding alternatives. That will crimp banks' ability to

grow profits going forward.

The four largest U.S. banks -- JPMorgan Chase & Co., Bank of

America Corp., Wells Fargo & Co. and Citigroup Inc. -- reported

a combined 5% drop in U.S. deposits that earn no interest in the

third quarter compared with a year ago. Customers withdrew more

than $30 billion from U.S. bank accounts that don't earn interest

over the year that ended June 30, the first such annual decline in

more than a decade, according to Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

data.

These deposits largely consist of business and consumer checking

accounts and are considered particularly valuable because banks can

use these no-cost deposits to make loans. As short-term interest

rates rise, they become even more lucrative.

Although the Fed started raising short-term rates in December

2015, banks have been able to boost earnings by charging higher

rates on loans while still paying depositors nearly nothing. But

after eight incremental Fed increases, some customers are moving

their money to capture higher yields elsewhere, threatening future

gains in bank profits.

Deposits that earn no interest are "the crown jewel of the bank

funding base," said Allen Tischler, a senior vice president at

Moody's Investors Service. "You start losing that and you end up

not being able to benefit from future rate increases."

Before the financial crisis, noninterest bearing deposits made

up a much smaller portion of money at banks. In 2007, the Fed

started cutting interest rates in an effort to combat mounting

economic problems. The central bank left them near zero for seven

years in an unprecedented move.

For many individual depositors, rates were so low for so long on

money-market and savings accounts across the industry that they

opted to keep their money in checking accounts that earned nothing

at all.

Noninterest deposits also became more attractive to corporate

customers because the government offered unlimited insurance for

many of these in the years after the crisis. Another incentive for

corporate customers: They often earn credits to cover fees on other

bank products when they put money in noninterest accounts. With

rates so low, those credits were often worth more than they would

have earned in an interest-bearing account.

When the Federal Reserve started raising rates in December 2015,

bank profits quickly benefited. That was because lenders started

charging more on certain loans like credit cards and lines of

credit to businesses, but didn't immediately pay depositors

more.

Slowly, lenders started paying higher rates to some savvy

corporate and wealth-management customers who might otherwise take

their money elsewhere. Still, money in noninterest accounts

continued to grow.

That is now reversing, even if slowly. Noninterest deposits of

around $3.2 trillion were equal to 26.3% of domestic deposits at

U.S. banks in the second quarter, according to FDIC data. Although

way above precrisis levels, the ratio is down from 27.5% a year

ago. That equates to about $30.6 billion less in noninterest

accounts.

The push for a better deposit deal is coming mostly from

businesses, which have more to gain because of their large amounts

of cash. Lenders including Bank of America, JPMorgan and regional

lender PNC Financial Services Group Inc. all said on earnings calls

that business customers moved money from accounts that earn zero

interest into accounts that pay more in the third quarter.

Bank of America, for instance, said average corporate

noninterest deposits fell 11% in the third quarter compared with a

year earlier. Meanwhile, corporate deposits that earned interest

rose 49% over that same period.

"Does it make sense to have the money in a noninterest account?

It used to," said Tom Hunt, director of treasury services at the

Association for Financial Professionals. When the trade group

surveyed its members who work in corporate finance, it found

companies in 2018 kept less of their short-term cash in bank

deposits and more in higher-paying investments.

The result: Not only do the banks have to pay up for more of

their deposits, they also have to pay more on the deposits that pay

interest. Both factors weigh on bank lending profit margins, which

are closely watched by investors.

"Non-interest-bearing deposits are the goose that lays the

golden egg for a bank," said Gerard Cassidy, an analyst at RBC

Capital Markets. Their decline, he added, is one reason the profit

boost from rising interest rates will likely end over the next year

or so.

Write to Rachel Louise Ensign at rachel.ensign@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 22, 2018 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2018 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

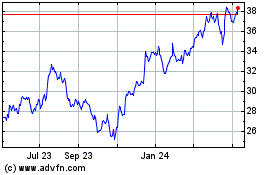

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

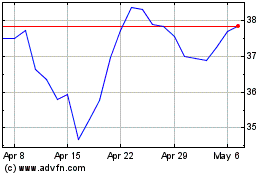

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024