4th UPDATE: Companies, Lawmakers Level Blame At Oil Hearing

May 11 2010 - 8:05PM

Dow Jones News

Irregular pressure readings, limitations in some testing and

deference on decision-making preceded last month's deadly oil-rig

explosion in the Gulf of Mexico, according to new details emerging

from testimony by oil company executives before the U.S.

Senate.

The testimony added to the picture of the accident on the

Transocean Ltd. (RIG) rig, which BP Plc (BP) was leasing in order

to drill an exploratory well with the help of Halliburton Co. (HAL)

employees. But a big question about whether procedures took place

in the correct sequence remained unanswered, as officials said that

none of them was familiar with the federally approved plans for

drilling an exploratory well that was located one mile below the

ocean's surface.

BP America President Lamar McKay told the Senate Environment and

Public Works Committee that "there were anomalous pressure-test

readings" in an exploratory well that was drilled into the ocean

floor before the explosion. Last month's blast has caused an oil

leak that has been spewing 5,000 barrels of oil a day into the sea

for roughly three weeks.

Halliburton safety chief Tim Probert, whose company was

cementing a pipeline into the hole bored into the sea floor, said

that only a particular type of test could have determined the

effectiveness of the cementing, but that test wasn't conducted.

Probert also said that the explosion occurred before Halliburton

had installed a final cement plug in the well on the ocean's floor,

at a time when workers had begun replacing heavy mud that had

exerted pressure on the well with lighter seawater, a sequence that

some people have called into question.

Probert said he wasn't sure how common it was to remove the

heavy mud before installing a cement plug that is the final barrier

put into place to guard against blowouts. That prompted Sen. Jeff

Sessions (R., Ala.) to angrily respond: "You do this business, do

you not? You're under oath, I'm just asking you a simple

question."

The hearing came as the Obama administration's Interior

Department announced plans to reorganize the Minerals Management

Service, which currently is responsible for both safety oversight

and collecting revenues from oil and gas leasing on federal lands.

Interior Secretary Ken Salazar, responding to criticism about the

potential for conflicts of interest, said the agency would be split

so the two functions would be separated.

Senate Environment and Public Works Committee Chairman Barbara

Boxer (D., Calif.) questioned BP America's chief on why the company

said it foresaw no problems when it requested government permission

to drill earlier this year. She also asked why Halliburton steered

clear of testing the cement "unless they ask you?"

Under repeated questioning, Prebert allowed that "we would feel

an obligation if we felt that the integrity of the cement was in

question."

As companies and lawmakers assigned blame, Senate Energy and

Natural Resources Committee Chairman Jeff Bingaman (D., N.M.) said

that multiple factors were at work.

"At the heart of this disaster are three interrelated systems--a

technological system of materials and equipment; a human system of

persons who operated the technological system; and a regulatory

system," he said. "These interrelated systems failed in a way that

many have said was virtually impossible. We need to examine closely

the extent to which each of these systems failed to do what it was

supposed to do."

BP's McKay, questioned repeatedly about the oil company's plans

to pay for costs related to the spill, said BP would pay all

"legitimate" claims. But he said that "claims have to have some

basis, have to have some substantiation."

Senators also said the oil industry and regulators weren't

prepared when disaster did strike. Speaking at a later hearing in

the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee, Sen. Arlen

Specter (D., Pa.), said oil companies could have had a containment

dome, which BP is now trying to lower onto the leaking well to

collect runaway oil, "ready for the spill rather than building one

after it happened."

Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R., Alaska) questioned why tests on using

chemical dispersants underwater hadn't been conducted before the

spill. BP is using dispersants to break up the oil on the ocean's

surface, but it has suspended the use of underwater dispersants

pending the outcome of Environmental Protection Agency tests.

Halliburton was performing the cementing work, which involves

filling up a space between the hole bored into the sea floor and

the casing inserted into the hole. Transocean Chief Executive

Steven Newman testified that "the one thing we know with certainty"

is that in the blast "there was a sudden, catastrophic failure of

the cement, the casing, or both."

"I agree," F.E. Beck, a petroleum engineer at Texas A & M

University, told the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee.

But he said that the wellhead casing "is also suspect."

BP has been unable to activate a blowout preventer, equipment

made of up heavy-duty valves that can shut of the well as a last

resort. Lawmakers questioned whether such equipment is subject to

enough testing.

"Why is it that the testing always seems to pass, and yet when

it was needed, it failed?" asked Sen. Bob Menendez (D., N.J.).

-By Siobhan Hughes and Corey Boles, Dow Jones Newswires;

202-862-6654; siobhan.hughes@dowjones.com

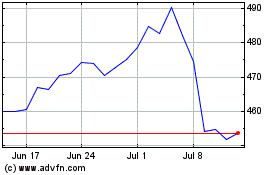

Bp (LSE:BP.)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

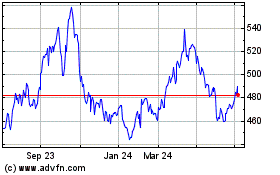

Bp (LSE:BP.)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024