Exxon Mobil Turns to U.S. Shale Basins for Growth

March 01 2017 - 11:44AM

Dow Jones News

By Bradley Olson

Exxon Mobil Corp. on Wednesday outlined an ambitious plan to

turn to prolific U.S. shale basins for growth, showcasing how the

oil giant now sees American production as a key to its future.

The company plans to spend about a fourth of its 2017 budget --

about $5.5 billion -- drilling in Texas, New Mexico and North

Dakota, tapping a vast inventory of wells that can turn a profit at

a price of $40 a barrel.

The U.S. increasingly appears at the center of a burgeoning

global revival after prices rebounded modestly and companies such

as Exxon have improved in their ability to profit due to lower

costs and feats of engineering.

Yet unlike some peers that plan to keep investment roughly flat

in future years, Exxon plans to increase spending to an average of

$26 billion a year from 2018 to 2020. The company plans $22 billion

in investments this year.

"Our job is to compete and succeed in any market, irrespective

of conditions or price," new Chief Executive Darren Woods said at

Exxon's analyst meeting in New York. It is his first major

appearance since taking over for Rex Tillerson, who stepped down to

become President Donald Trump's secretary of state.

"The ultimate prize in the Permian is significant," he said,

noting that the land the company controls in the West Texas and New

Mexico oil region may hold the equivalent of as much as 6 billion

barrels of oil and natural gas. The company also plans to invest in

Guyana, where it made a major discovery in 2015.

He also warned that because shale drilling has the ability to

ramp up more quickly than other kinds of production, it has the

potential to "temper" price volatility.

Mr. Woods, a 52-year-old engineer who rang the bell Wednesday

morning on the New York Stock Exchange, inherited an array of

challenges at the world's largest publicly traded energy company.

Debt has soared in recent years. Growth continues to be elusive.

Returns in Exxon's oil-and-gas production business are at the

lowest levels in decades.

Activists are targeting the company over whether it concealed

its prior knowledge of climate change, charges Exxon has denied and

said are part of a conspiracy by antagonists to smear its

reputation. Some investors meanwhile have grown enamored of smaller

producers with a longer record of stopping and starting production

on a dime in U.S. shale fields.

That is a comedown from Exxon's exalted status a decade ago,

when the company was a Wall Street darling, the biggest and most

profitable publicly traded corporation in the world. In 2007, Exxon

generated more than $40 billion in profits, then a record, most of

which came from oil-and-gas drilling in many of the world's

continents.

The recent crash in oil prices has exposed weaknesses in a

record of stable profits and returns that was once unimpeachable.

Net income last year was $7.8 billion, the lowest since 1996,

before Exxon bought rival Mobil Corp. for $82 billion in 1999.

Exxon's debt has risen as the company increased borrowing to pay

for dividends, one of several factors that prompted Standard &

Poor's Global Ratings last year to take away the triple-A credit

rating it had held since the Great Depression.

Some analysts are urging Mr. Woods, whose rise at the company

occurred within Exxon's sprawling network of refineries and

chemical plants, to shake up the cloistered descendant of John D.

Rockefeller's Standard Oil.

Exxon has lost cachet among institutional investors in recent

years: Most portfolios hold a smaller proportion of Exxon stock

than its relative size in the S&P 500 index, according to

Evercore ISI analyst Doug Terreson.

This "underscores investor concern" over Exxon's strategy, Mr.

Terreson wrote in February, arguing that the company should make

returns a priority over growth, a move taken up by peers including

Chevron Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell PLC.

Many analysts believe Mr. Woods is the perfect person to put the

company on a new course. Identified years ago as a future leader

through Exxon's meticulous process of winnowing its management

ranks, Mr. Woods was an architect of a yearslong effort that

reduced Exxon's footprint as a global fuel processor, according to

people familiar with his work.

He helped lead an effort to sell refineries or gas stations that

were less profitable and less interconnected with Exxon's other

operations. As he occupied various leadership roles in those

businesses, Exxon shaved off 1.3 million barrels a day of refining

capacity, about a fifth of the total in 2007. The company sold off

thousands of gas stations from Japan to Canada.

Mr. Woods, a staunch advocate of "integration," or the effort to

squeeze money from every aspect of the business -- including

producing, shipping, refining and processing oil and gas -- turned

to investments that would provide numerous options for turning a

profit. Those include equipment allowing a refinery to process

heavier crude that is cheaper than other grades, or making more

chemicals or niche products that can be sold at a premium.

Write to Bradley Olson at Bradley.Olson@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 01, 2017 11:29 ET (16:29 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

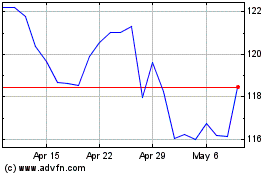

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

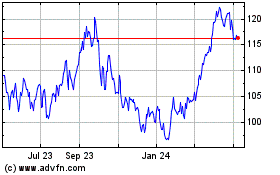

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024