Oil companies are pumping more crude off the U.S. coast in the

Gulf of Mexico, a surprising trend that shows the resilience of the

nation's energy industry.

Despite the worst price downturn in a generation, so much oil is

starting to pour forth from offshore fields near Louisiana and

Texas that it is partially offsetting declining output from shale

regions on shore and propping up total American oil output.

The U.S. is currently pumping about 8.7 million barrels a day,

480,000 less than at the end of last year, according to the Energy

Information Administration, as low prices spur companies to shut

down new exploration and some existing shale-oil wells begin to

peter out.

Production is forecast to drop further to 8.5 million barrels a

day later this year.

But well over 500,000 barrels a day of new Gulf crude is set to

come online this year and next, according to a Wall Street Journal

analysis of government data, company presentations and regulatory

filings.

The Gulf surge threatens to prolong the glut of crude that has

built up in storage around the U.S. and helped push down prices,

said Roger Diwan, vice president of financial services at IHS

Energy.

"The projects are coming faster and sometimes bigger than

expected," he said. "The ramp-up seems to have accelerated during

low prices."

Gulf production is rising in part because a handful of massive

oil fields sanctioned for development years ago by companies like

Freeport McMoRan Inc. and BP PLC when prices were higher are

starting to pump oil this summer and fall.

But it is also going up because companies are finding that

smaller satellite fields can be tapped relatively cheaply by

linking them to existing offshore oil platforms by way of

underwater pipelines.

While production from many of these so-called tieback wells is

reflected in forecasts from banks and analysts, the Journal

analysis found that some of it appears to have been

undercounted.

American offshore oil production is on track to set a record in

2017, with 1.91 million barrels flowing out of the Gulf by year's

end, according to the U.S. Energy Department. That would be a 24%

surge over 2015's offshore oil output of 1.54 million barrels a day

and would beat a previous high of 1.56 million barrels a day set in

2009, the year before BP's Deepwater Horizon oil spill disaster

temporarily shut down drilling, federal data show.

While the conventional wisdom in the energy industry was that

deep-water oil development was too expensive at current prices of

around $50 a barrel, producers looking to squeeze out profits from

existing investments have rushed to tap tiny wells offshore and

connect them to oil platforms.

One of them is Exxon Mobil Corp. It started pumping 13,000

barrels a day at the end of April from a well 200 miles south of

New Orleans known as Julia, whose production is being piped back to

Chevron Corp.'s Jack/St. Malo platform. Exxon expects

Julia's production to eventually hit 34,000 barrels a day.

Big oil companies, including BP and Royal Dutch Shell PLC as

well as independent exploration outfits like Anadarko Petroleum

Corp. and Noble Energy Inc., are pursuing tiebacks. None would

quantify how much production they expect to add from the projects,

citing competitive reasons.

Noble, which has prioritized tiebacks over some shale

development, nearly doubled its Gulf output in the first quarter

and has another offshore well starting to pump later this summer.

Anadarko has more than 30 tieback well prospects in satellite

fields, and will drill up to seven this year, according to Bob

Gwin, chief financial officer.

"At $60 oil, which hopefully is on the horizon, these

opportunities have better than a 70% rate of return," Mr. Gwin told

analysts at the UBS Global Oil and Gas Conference in Austin last

month.

Tieback wells are drilled in fields not large enough to justify

the hefty expense of building new giant floating installations in

the Gulf. Some tieback wells are profitable when oil trades as low

as $25 to $30 a barrel, and many more can make money when crude is

between $30 and $40 a barrel, according to analysts at Wood

Mackenzie, a consulting firm in Houston.

Constructing the massive offshore oil platforms that bob in

thousands of feet of water and suck crude up from beneath the ocean

floor can take nearly a decade and billions of dollars. Once built,

"you might as well make the most of it" by maximizing the oil each

platform pumps and processes, said Terry Yen, an analyst with the

U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Deep-water drilling costs have fallen and will continue to drop

as long-term contracts on rigs expire, according to IHS

Petrodata.

Companies are also getting better at accessing deep-water finds.

Shell saved $1 billion drilling its Stones project in ultra-deep

waters 200 miles southwest of New Orleans, which will start up next

year, by using a slim-well design offshore engineers borrowed from

onshore shale operations.

Chevron recently executed a tieback to its Tahiti platform 190

miles south of New Orleans using a technique that allowed it to tap

two oil reservoirs stacked on top on each other, resulting in a

well that will produce 50% more oil and gas than originally

thought, the company said in a recent earnings call.

Gulf production has also grown thanks to the ingenuity of

smaller players such as LLOG Exploration Co., a private deep-water

driller based in Covington, La.

It pioneered a platform-building process that it can bring new

projects online in half the time it takes bigger rivals, said

Gordon Loy, a researcher at Wood Mackenzie.

Write to Erin Ailworth at Erin.Ailworth@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 23, 2016 14:05 ET (18:05 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

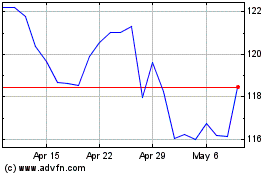

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

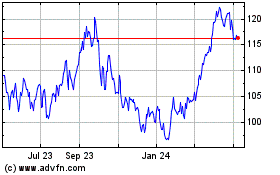

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024