By Sarah Kent and Robb M. Stewart

The world's largest energy companies are sidelining big ideas

that they touted just a couple of years ago as the future of the

industry.

From Australia to the U.S. Gulf Coast, the casualties include

ultra-deep-water drilling projects, huge boats that serve as

floating liquefied natural gas factories and technology that could

drastically reduce emissions from burning fossil fuels. Royal Dutch

Shell PLC, Chevron Corp. and Australia's Woodside Petroleum PLC are

among the big companies to pull back or delay ambitious

projects.

Shell hammered home the message on Wednesday after reporting

first-quarter profits that were down 83% from the same period a

year before. The Anglo-Dutch oil giant said it would cut its

capital spending budget another 10%, to $30 billion this year.

"To be brutally honest, any large new greenfield investment

whether floating LNG, deepwater or elsewhere is under very strict

critical review for cost levels and return simply because of where

the industry is," Shell Chief Financial Officer Simon Henry said in

a conference call.

As of March, the oil industry has deferred or canceled $270

billion in projects since crude prices began crashing nearly two

years ago, according to estimates from Norway-based consultancy

Rystad Energy. The bulk of those spending cuts have involved

high-tech projects once seen as crucial to sustaining global energy

supplies.

It is a dramatic turnaround from the last decade when surging

demand for oil and dwindling resources sent crude prices soaring

and big energy companies pushing into new frontiers regardless of

the cost.

According to information and analytics firm IHS Inc., the

oil-and-gas industry spent about 15% less on research and

development in 2015, when crude oil prices averaged roughly $50 a

barrel, compared with 2014, when prices averaged close to $100 a

barrel.

"We see a pullback from customers on really complex projects,"

said Kishore Sundararajan, chief technology officer at GE Oil &

Gas, General Electric Co.'s energy industry services division.

Efforts to re-create the U.S. shale boom abroad have also

suffered. The volumes unleashed by the technique of hydraulic

fracturing are largely to blame for the current market downturn,

but exporting the technique abroad have been stalled by political,

geological and technical reasons, compounded by slumping energy

prices.

Now, the focus increasingly is on technologies that can reduce

costs and improve efficiency as the world's biggest oil companies

continue to slash billions from their budgets and cut thousands of

jobs.

ConocoPhillips last week said it would reduce spending by a

further $700 million this year, drawing about half the savings from

a decision to forgo deep-water drilling in the Gulf of Mexico. In

March, Exxon Mobil Corp. announced plans to cut its capital

spending 25% in 2016 and said it would be "highly selective" about

investments. BP last month raised the prospect that it could pull

back spending further if the oil market remains under pressure next

year.

Prices have risen to their highest levels this year, with Brent

crude, the international benchmark, reaching $48.50 a barrel at the

end of April. Even so, companies remain cautious on returning to

complex and expensive new areas.

"We wouldn't be looking to significantly ramp up [even] if we

see oil prices come back up to $60 a barrel," BP CFO Brian Gilvary

told analysts in April. "We're really looking at what we can do

around the margins of the existing portfolio."

Among the most high profile victims of the price crash are

floating LNG plants -- huge ships that are essentially seafaring

factories built to exploit remote gas fields. Natural gas was long

transported only by pipeline; LNG plants turn the gas to a liquid,

allowing for shipment to markets around the world.

Woodside Petroleum last month shelved plans for a floating

operation at its Browse field off Australia's western coast that

analysts estimated would have cost about $40 billion. The company

says it still favors floating LNG, but it isn't going to happen in

the current market environment.

Work on such floating gas factories has been under way since the

early 1990s, but there still isn't one in operation. Slumping

prices and a looming oversupply of natural gas is gradually killing

off nascent plans for further projects.

"Big heavy capital projects at the moment are not in favor and

so putting huge amounts of money into that at the moment is

probably not the wisest thing to do," Woodside Chief Executive

Peter Coleman said in April.

Costly efforts to make the oil sector more environmentally

friendly through carbon capture and storage also are vulnerable to

the oil price slump. Known as CCS, the projects grab carbon dioxide

released from industrial processes and funnel it underground.

Such CCS projects are seen by many energy-sector analysts as

crucial to preventing catastrophic climate change, and many in the

industry have also been vociferous advocates of the technology.

Shell and Chevron are leading ambitious projects in Canada and

offshore of Australia, respectively. But follow-on projects in the

oil sector have been slow to get off the ground. CCS remains

expensive and often dependent on government subsidies. Shell last

year scrapped a proposal for a plant in the U.K. after the

government withdrew GBP1 billion in support. The low oil price puts

additional pressure on any new project.

"It is still early days for these types of projects and they are

costly, " Chevron CEO John Watson said in Perth last month.

In the deep waters of the Gulf of Mexico, oil companies are

examining new opportunities warily. Chevron wrote off $500 million

last year after it canceled its Buckskin-Moccasin development

project in the region. BP has yet to make a final decision on

whether to proceed with the much-delayed second phase of a project

that taps oil and gas reserves at depths of 4,500 feet.

Of course, not every big project is being put off. But those

getting the go-ahead are taking cost cuts. For instance, BP has

said it still expects to go ahead with its so-called Mad Dog

project in the Gulf but believes more savings are possible. It has

already squeezed around 50% from the cost of early plans that

involved a customized design and came in at around $20 billion.

Shell opted to move ahead with its Appomattox project, targeting

production of 175,00 barrels of oil equivalent a day from a depth

of 7,200 feet in the Gulf of Mexico -- one of a handful of

developments to get approval last year -- after bringing down costs

by 20%.

The company's giant Prelude floating LNG tanker, currently under

construction, will likely be one of the first to test the

technology. The project offshore Australia is expected to be in

production by 2018.

Write to Sarah Kent at sarah.kent@wsj.com and Robb M. Stewart at

robb.stewart@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 04, 2016 15:19 ET (19:19 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

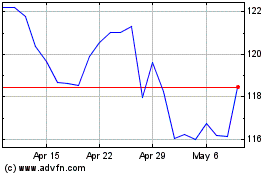

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

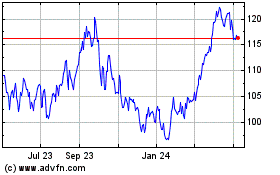

Exxon Mobil (NYSE:XOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024