By Liz Hoffman and Alison Sider

Energy Transfer Equity LP can escape its deal to buy rival

pipeline operator Williams Cos. after a Delaware judge ruled that

its fears of an unexpected tax bill were genuine and not a ploy to

get out of an acquisition it no longer wanted.

Vice Chancellor Sam Glasscock III ruled Friday that Energy

Transfer's lawyers weren't deliberately sandbagging the merger when

they said they couldn't deliver a necessary opinion letter on the

deal's tax treatment, as Williams argued during a two-day

trial.

Without the legal opinion, the deal -- originally valued at $33

billion when it was signed last fall -- can't close by a Tuesday

deadline, which had been agreed upon by both companies.

Williams said Friday it disagreed that Energy Transfer has a

right to terminate the merger and urged its shareholders to vote

for it Monday.

"If ETE attempts to terminate the merger Agreement, Williams

will take appropriate actions to enforce its rights under the

merger agreement and deliver its benefits to Williams'

stockholders," the company said.

Energy Transfer said in a statement late Friday that its lawyers

likely won't be able to deliver the necessary tax opinion before

the company is allowed to terminate the merger.

Williams had accused Energy Transfer of using the tax issue to

wriggle out of the takeover, which its empire-building chairman,

Kelcy Warren, had come to regret as the oil bust dragged on.

"Motive to avoid a deal does not demonstrate lack of a

contractual right to do so," Mr. Glasscock wrote. "A desperate man

can be an honest winner of the lottery."

The trial this week in the Delaware Court of Chancery had been

closely watched by deal makers far beyond the energy patch. Buyer's

remorse on such a large scale is unusual, and the fact that this

trial hinged on legal opinions and tax structuring, the critical

sausage-making that is often taken for granted in big takeovers,

fanned interest among mergers-and-acquisitions specialists.

The deal, which would create a 100,000-mile U.S. network of

oil-and-gas pipelines, was signed last fall in what proved to be

the middle innings of a severe downturn in energy prices. While it

originally valued Williams at $33 billion, a steep slide in Energy

Transfer shares had cut its value to about $20 billion on the eve

of the trial.

Williams is considering an appeal, according to a person

familiar with its matter. It could also sue Energy Transfer for

damages, should it lose an appeal. Williams has said the deal's

collapse would cost it between $4 billion and $10 billion in lost

value for its shareholders, who are set to vote on the transaction

Monday.

On Tuesday, Energy Transfer can notify Williams that it intends

to terminate the transaction.

The takeover was a bold play from a veteran deal maker. Mr.

Warren built his pipeline empire through acquisitions and has

boasted of finding bargains in troubled markets, much like the one

that settled over the energy industry two years ago.

Last spring, he made an unsolicited bid for Williams, whose

crown jewel is the 10,000 mile Transco pipeline running from Texas

to New York City. The two companies had previously competed against

each other to buy Southern Union Co. in 2011, a bidding war Energy

Transfer won.

After a few months of resistance, a split Williams board agreed

to a takeover in September.

But by early this year, Mr. Warren no longer wanted to do the

deal as structured. He feared the deal's $6 billion cash portion,

which had to be borrowed, would saddle Energy Transfer with too

much debt and trigger ratings downgrades and an "implosion" across

the interlocking web of companies he controls, according to court

testimony.

In January, Mr. Warren met with top executives and advisers,

including litigation attorneys, to discuss Energy Transfer's

options, according court filings. Around the same time, he also

asked Williams to consider terminating the deal, Williams Chairman

Frank MacInnis testified.

In March, Energy Transfer's lawyers discovered a problem with

the deal that could bring unexpected taxes and said they wouldn't

be able to give a legal opinion the merger would be tax-free.

Without the opinion from its lawyers at Latham & Watkins,

Energy Transfer doesn't have to complete the deal.

Such letters are typical in complicated takeovers and

essentially require lawyers to opine with enough certainty that the

Internal Revenue Service won't later slap the company with a tax

bill.

It is rare for lawyers to lose their nerve on an opinion between

a deal's signing and closing. Energy Transfer said the decline in

its own share price was to blame, creating a taxable gap between

the value of Williams's assets and the value of the consideration

-- mostly Energy Transfer shares -- that Williams's shareholders

would receive.

During the trial this week, Energy Transfer's head of tax, Brad

Whitehurst, testified that he had misunderstood a key component of

the deal and only realized his mistake while he was researching

ways for Energy Transfer to cope with deteriorating energy markets,

such as cutting Energy Transfer's cash payout.

"It's your worst nightmare. Your heart stops," Mr. Whitehurst

testified. "You panic because that's that realization that you've

got a major problem with your tax structure and it...could result

in a significant tax liability."

Williams, whose advisers called the worries "bogus," sued in

Delaware court last month. It argued Energy Transfer hadn't tried

hard enough to find a solution or considered fixes proposed by

Williams' advisers.

Mr. Glasscock disagreed. He said Latham & Watkins was acting

"in good faith" and rejected Williams' implicit argument that the

law firm was going out on a legal limb for a top client.

"Reputational effects surely outweigh any benefit of an

unethical deference" to Energy Transfer's wishes, he wrote. "While

this deal is, certainly, a lunker, Latham has even bigger fish to

fry."

The decision is a big one in M&A circles. Few mergers give

cold-footed buyers the ability to walk away cleanly. But many hinge

on receiving law firm opinions on everything from taxes to

regulatory matters. Those may become de facto escape hatches for

regretful acquirers, deal lawyers said.

"Usually, everybody wants a deal to happen, so you find a

workaround," said Elias Hinckley, a tax and energy specialist at

Sullivan & Worcester. "But when the market changes and people's

desire to do the deal changes, the question is: How hard do you

have to try?"

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com and Alison Sider at

alison.sider@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

June 24, 2016 21:17 ET (01:17 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

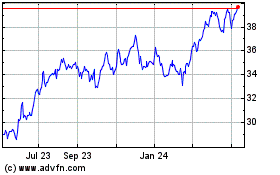

Williams Companies (NYSE:WMB)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

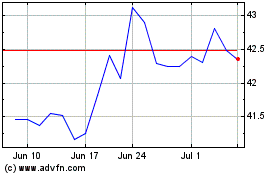

Williams Companies (NYSE:WMB)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024