By Liz Hoffman and Alison Sider

Kelcy Warren became a billionaire oil man by making deal after

deal, including purchases of thousands of miles of pipelines after

Enron Corp. collapsed. Now he is suffering from a severe case of

buyer's remorse.

As low oil prices spread pain throughout the energy industry,

Energy Transfer Equity LP, the Dallas company where Mr. Warren is

chairman, is scrambling to restructure or escape a $33 billion

agreement announced just seven months ago to acquire Williams Cos.,

based in Tulsa, Okla. The deal would create a 100,000-mile network

of pipelines.

Mr. Warren, 60 years old, has overseen a series of moves that

could torpedo the biggest acquisition of his life, such as an

unusual convertible preferred share issue that would dilute

Williams shareholders and increase his own stake in the combined

company.

When Williams Chairman Frank MacInnis called in February to

complain, Mr. Warren responded curtly, according to Mr. MacInnis.

"No one was going to tell him how to run his company," Mr. MacInnis

said in the unredacted version of a court filing reviewed by The

Wall Street Journal. The comment is crossed out of a publicly

available copy of the filing.

Energy Transfer disputes the comment but says the two men have

talked a number of times about what would be in the best interest

of shareholders. The company says Mr. Warren isn't trying to kill

the deal but is emphatic that it needs to be restructured.

The deal, one of the largest announced in 2015, is now in danger

of becoming one of the highest-profile corporate casualties of the

oil bust. After Messrs. Warren and MacInnis announced the agreement

on Sept. 28, oil prices fell about 40%, though they have since

rebounded. The share prices of both companies are still down by

roughly half. The tumult also cost Energy Transfer's chief

financial officer his job.

The mess shows how vulnerable many deals are to souring

financial markets. Deals touted as mutually beneficial when

announced can quickly turn better for one side than the other. The

same thing happened when credit dried up in the financial crisis

and droves of buyers scrambled to get out of deals.

So far this year, about $378 billion in U.S. mergers and

acquisitions have been abandoned, more than 40% higher than in all

of 2015, according to Dealogic. This year's broken-deal total will

be a record even if no more deals fall apart.

Recent examples include Pfizer Inc.'s proposed $150 billion

takeover of fellow drugmaker Allergan PLC and the $35 billion

merger of oil-field services companies Halliburton Inc. and Baker

Hughes Inc., which crumbled under pressure from U.S. regulators.

Honeywell International Inc. and Canadian Pacific Railway Ltd.

walked away from reluctant takeover targets.

Williams has filed lawsuits against Energy Transfer and Mr.

Warren over the share issuance, alleging that it cheats Williams

shareholders.

After initially resisting the deal, Williams now is considering

asking a judge to force Energy Transfer to complete the takeover,

say people familiar with the matter. Williams says a failed deal

would cost its shareholders $10 billion in lost value.

Mr. Warren has long kept a tight grip on his sprawling pipeline

empire, launched two decades ago. In addition to Energy Transfer,

he essentially controls three other publicly traded companies

stitched together so complicatedly that some analysts decline to

follow them, they say.

He also is one of the country's richest men, with a net worth

estimated at $7 billion by Forbes. Mr. Warren owns a private island

in Honduras and an 8,000-acre property near Cherokee, Texas, that

was once an exotic-animal ranch and is still home to roving zebras

and buffalo.

His 23,000-square-foot Dallas mansion, bought for $30 million in

2009, includes a bowling alley and a baseball diamond that features

a scoreboard with "Warren" as one of the teams.

He is an avid music fan and owns an independent recording studio

that produced in 2014 a Jackson Browne tribute album with cover

songs by musicians such as Bonnie Raitt and Don Henley.

Mr. Warren has boasted of seeing opportunity in downturns. He

launched Energy Transfer in the wake of Enron's demise and then

expanded.

In 2012, another company he runs, Energy Transfer Partners,

agreed to buy Sunoco Inc. for $5.3 billion while Sunoco was in the

middle of a complex restructuring. The $5.7 billion takeover of

pipeline company Southern Union Co., also in 2012, came after a

hostile bidding war.

In 2013, he hired Jamie Welch, a longtime energy investment

banker at Credit Suisse Group AG who shared Mr. Warren's hearty

appetite for deals.

The two men saw an opening in the oil rout that started in 2014,

which Mr. Welch described as "a once-in-a-lifetime

opportunity."

During a brief uptick in oil prices early last year, Mr. Warren

told analysts: "This is going to sound odd to you, almost sadistic,

but I was disappointed to see a rebound in crude prices...I was

excited to see who might be more vulnerable if we saw this market

continue a downward trend."

Energy Transfer set its sights on Williams and its crown jewel:

the 10,000-mile Transco gas pipeline. But Williams stiff-armed

Energy Transfer for months, according to securities filings.

When Energy Transfer made an all-stock offer in June then valued

at $48 billion, Williams rejected it as too cheap and plowed ahead

with plans to absorb an affiliate.

By the fall, Williams's outlook had worsened. In addition to

sapping pipeline demand, oil's slide had hurt Williams's

gas-processing business, which is especially vulnerable to price

swings. A big customer, Chesapeake Energy Corp., looked

increasingly troubled, too.

At a meeting of Williams's board of directors in Tulsa in

September, the company's advisers said investors were losing

patience, according to people familiar with the matter.

Hopes briefly flickered for a white-knight transaction with

Warren Buffett-backed MidAmerican Energy Co., which expressed

last-minute interest, but talks went nowhere, some of the people

say.

Energy Transfer kept pushing for a deal, but the Williams board

was divided seven to six against it. With tensions running high,

the group took a break for dinner. Unable to find a private dining

room big enough to accommodate them, they split into two groups,

one "for" and the other "against," people familiar with the matter

say.

When the meeting reconvened in the morning, two directors had

changed their minds. The deal was approved by an 8-5 vote.

Energy Transfer shareholders, who had bid up the stock price

when the offer first surfaced, were unimpressed with the details of

the takeover announcement. Energy Transfer shares fell 13% in one

day.

Early signs that regret was setting in came when Mr. Welch,

Energy Transfer's finance chief, painted the deal unfavorably in

conversations with some Williams shareholders in January. He even

suggested that they consider voting against it, these people

say.

The merger contract is written with unusually tight provisions

on how Energy Transfer can get out of the deal. Williams

shareholders can vote it down.

Word of Mr. Welch's efforts, which were earlier reported by the

New York Times, filtered back to Williams. Integration meetings

were postponed and progress slowed, people familiar with the matter

say.

Energy Transfer's public statements about the deal got

noticeably cooler. In March, the company slashed its estimate of

annual cost savings at the combined companies by more than 90%,

said it would suspend cash distributions for at least two years and

warned that a credit-rating downgrade was possible because of the

combined companies' heavy debt load.

Energy Transfer also backed away from its promise to keep a

major presence in Williams's hometown of Tulsa after the deal is

completed.

Last month, Energy Transfer said its lawyers couldn't guarantee

the transaction would be tax-free to Williams investors, a

condition of the merger's completion. Williams disputes Energy

Transfer's legal position and says it is an attempt by Energy

Transfer to wriggle out of the deal.

On an earnings call last week, Mr. Warren was dour about the

takeover. "Absent a substantial restructuring of this transaction,

which Energy Transfer has been very willing and actually desiring

to do -- absent that, we don't have a deal," he said. Mr. Warren

declined to comment for this article.

One big sticking point is the $6 billion cash portion of the

deal, or $8 a share. Energy Transfer and some analysts are worried

that the cash payout would saddle the combined company with too

much debt.

"Kelcy is firing every bullet he has," says Benjamin Michaud, an

analyst at asset manager H.M. Payson & Co., which owns $10

million of Williams shares and supports the takeover. "But from the

standpoint of a Williams shareholder, $8 [a share] is very

significant."

Some Williams shareholders say there is so much acrimony between

the two companies that it is hard to imagine them getting along if

the deal goes through. "There's got to be a lot of bad feelings on

both sides of the aisle," says Jay Rhame, a portfolio manager at

Reaves Asset Management.

Tulsa Mayor Dewey Bartlett Jr. says that he sees nothing good

about the proposed takeover and that he recently told Mr. MacInnis

that in a meeting in New York. Mr. MacInnis declined to comment for

this article.

The biggest flashpoint is the convertible-share issuance. In

March, Energy Transfer insiders, including Mr. Warren, President

John McReynolds and two directors, swapped their existing shares

for special units, which would forgo cash distributions over the

next nine quarters.

Those units are convertible into regular shares at a discount to

the market price, giving their holders a bigger stake than they

started with.

Energy Transfer has said the move would save $518 million to

help pay down debt. The company says it wanted to offer the shares

to all its investors, but Williams withheld its consent. Williams

says it opposed the move because it would hurt Williams

shareholders.

In April, Energy Transfer said it intended to suspend cash

distributions after the merger, meaning the insiders will have

given up nothing but still stand to receive more equity when the

units are converted in 2018.

People familiar with the matter say Mr. Welch disagreed about

how far Energy Transfer could go to try to get out of the takeover

and balked at the convertible-share issuance. The finance chief

told Mr. Warren the share issuance would damage Energy Transfer's

reputation on Wall Street. He also told his boss that he wouldn't

publicly defend the move, these people say.

That was the last straw in a relationship that already had

become troubled. The cash portion of the deal terms was Mr. Welch's

idea, according to people familiar with the matter. He had argued

that by including more cash, Energy Transfer could issue less stock

and keep more of the upside of the combined company.

But as the industry's outlook worsened and investors grew

concerned about the combined company's debt load, what seemed like

a win for Energy Transfer became a liability.

Mr. Warren ordered Mr. Welch's firing, according to people

familiar with the matter. The company announced Feb. 5 that he had

been replaced.

Mr. Welch has sued Energy Transfer for compensation he says he

is owed by the company. Mr. Welch has said his termination was

"motivated by an agenda unrelated" to his performance as chief

financial officer.

Mr. Warren told analysts that "the decision was made by me that

we needed to make a move, and we did."

Last month, Williams filed one lawsuit in Delaware seeking to

undo the convertible preferred share issue and another in Texas

alleging that Mr. Warren interfered with the deal. Energy Transfer

responded with a countersuit and says Williams breached the merger

agreement by refusing to give its consent for the shares to be

offered to all investors.

Unless the companies reach a surprise settlement, the deal's

fate will likely be decided by a judge in Delaware. A court hearing

is scheduled for mid-June.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 10, 2016 14:24 ET (18:24 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

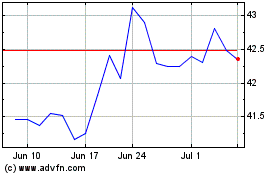

Williams Companies (NYSE:WMB)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

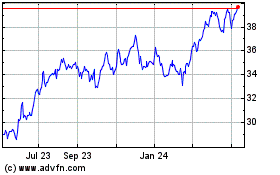

Williams Companies (NYSE:WMB)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024