By Emily Glazer

As Wells Fargo & Co.'s sales-tactics scandal unfolded,

investors, regulators and politicians asked how improper practices

could have persisted for so long. One possible reason: bank

branches were given a heads up before Wells Fargo's internal

monitors landed for inspections.

Managers and employees at the bank's roughly 6,000 branches

across the U.S. typically had at least 24 hours' warning about

annual reviews conducted by risk employees, current and former

Wells Fargo employees and executives said. That gave many employees

time to cover up improper practices, such as opening accounts or

signing customers up for products without their knowledge.

More than a dozen current and former employees of the bank

across California, Arizona and New Jersey, for instance, said they

forged or saw colleagues forge signatures on documents or shred

papers that could have indicated accounts were opened without

authorization.

Often, managers would call for all hands on deck at a branch to

stay late into the evening -- or sometimes all night -- to shred

documents or forge signatures if they weren't there, some current

and former managers said.

For instance, they would go through desks to find signature

cards that hadn't been approved, make sure wire forms had been

filled out properly and that documents in a "control binder" like

cash or teller audits were filled out, said Ivan Rodriguez, a

former branch banker at Wells Fargo for about six years until

2013.

Some branches that opened accounts for customers without the

customer present would cut and paste a signature the bank had on

file for the customer and add it to the required signature card,

Mr. Rodriguez said.

"You became numb to it," he added. "It became pretty

normal."

A Wells Fargo spokeswoman said the bank has boosted oversight,

monitoring and accountability so unethical practices don't happen

again. That includes investing millions in staffing, mystery shops

by a third party, unannounced branch inspections on employee sales

behavior and an increase in branch visits by its internal

auditors.

The bank has been under fire since September when it entered a

$185 million settlement and enforcement action with regulators and

a city official over opening as many as 2.1 million accounts using

fictitious or unauthorized information. Wells Fargo still faces a

spate of state and federal investigations, including from the

Justice Department and the Securities and Exchange Commission.

In the scandal's wake, Wells Fargo has been changing procedures

and trying to tighten internal checks, said Vic Albrecht, who has

led risk management for the retail bank since September. Last fall,

it piloted a surprise sales-practices inspection that previously

didn't exist to ensure there isn't undue sales pressure and

customers get appropriate products, among other checks, he

said.

Around 100 of these "Conduct Risk Reviews" have been completed

based on possible risks or complaints. Top retail-banking

executives who typically oversee hundreds of branches, risk

executives and company lawyers are aware of the results, Mr.

Albrecht said.

But the other system, now known as "Branch Control Review,"

still gives a 24-hour notice so branch managers can staff

appropriately and it doesn't interrupt customer service, he said,

though advance notice and other parts of the review could change in

the future. It measures "operational integrity," according to an

internal bank document reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. That

system, alongside the bank's "Quality of Sales Report Card" that

checks signatures, procedures and funding, are part of a new branch

"risk score." This will be factored into employees' compensation

under a new plan rolled out to staff this month, according to plan

documents.

Bank-branch audits are common in the industry, especially to try

to spot risks related to large transactions, paperwork logs and

cash shipments. Other big banks, such as Bank of America Corp.,

Citigroup Inc. and J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. typically have

surprise branch audits, or checks, at least once a year, said

people familiar with the banks, who added that branches didn't get

notice ahead of time.

"They need to audit business as usual, not to see somebody put

on their Sunday best clothes," said Jeffrey Sonnenfeld, professor

and associate dean for leadership studies at Yale School of

Management. "Mystery shoppers...don't give advance notice to the

stores that they're coming."

Banks are expected to have three lines of defense to spot

irregularities or problems: its business executives,

risk-management professionals and internal auditors. The board of

directors is supposed to add another layer for checks and balances.

It appears some of these were lacking at Wells Fargo, according to

regulators.

"Had these structure elements been functioning properly, they

would have prevented the type of abuses we have witnessed at Wells

Fargo," Thomas Curry, head of the Office of the Comptroller of the

Currency, said at one of two congressional hearings about the

bank's sales practices.

At Wells Fargo, retail-bank risk executives -- some branch

employees called them auditors -- typically traveled district by

district to check on branches, some current and former employees

said. But retail-bank executives would usually receive anywhere

from 24 to 72 hours' notice of the inspections, and branch managers

typically got one day's heads up, these people said.

Some of those bank managers would meet with operations staff in

their districts to discuss issues auditors were finding so they

could fix those in advance of another audit, one of these people

said.

Internally, the advance notice -- known to some within the bank

as an open-book test -- was considered standard, these people said.

Only in recent years did much of the operational-control checks

move to electronic forms auditors would gather in advance, making

it harder for branch employees to fake records.

The inspectors would examine, for instance, how many accounts

were funded, whether signature cards existed for accounts opened in

the last 90 days, and if employees knew the opening and closing

procedures of the branch, among other checks, these people

said.

"The volume of business you did was humongous, so the dotting of

Is and the crossing of Ts was not that great," one of these people

said. "Growing the business was primary: the more successful you

were, the higher the goals were. So you had to keep up."

Write to Emily Glazer at emily.glazer@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 24, 2017 05:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

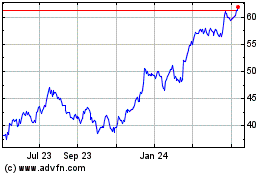

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

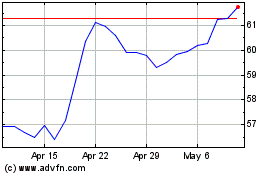

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024