By James R. Hagerty

When U.S. Army Air Corps pilot Richard Cooley woke up in a

French hospital in December 1944 and discovered he had lost his

right arm in a plane crash, he knew he would be all right.

"I would make a living," Mr. Cooley later wrote. "I would find a

wife. I would be happy. But I would probably never play football

again." For that, he wept.

Then he moved on. He graduated from Yale University, became

chief executive of Wells Fargo & Co., married four times,

taught business at the University of Washington, and excelled at

golf, tennis and squash. He batted up and down the hills of San

Francisco in a Mustang with a stick shift. He devised his own

method for tying a necktie; it involved using his left hand, his

prosthetic right limb and his teeth.

He attended Roman Catholic Mass virtually every day of his adult

life. He often declared himself the luckiest man he knew.

Mr. Cooley died Sept. 21 at his home in Seattle. He was 92 and

had been suffering from multiple myeloma.

As CEO of Wells Fargo for 16 years starting in 1966, he was

known for grooming talent. Among Wells alumni from his era who

became CEOs of other big banks were Richard Rosenberg ( Bank of

America), John Grundhofer ( U.S. Bancorp) and Frank Newman (Bankers

Trust). Mr. Rosenberg said Mr. Cooley had "a very special quality

of leadership." The former Bank of America chief added that he

usually lost when he played tennis with his one-armed

colleague.

Richard Pierce Cooley, known as Dick, was born Nov. 25, 1923, in

Dallas and grew up in the New York suburb of Rye. He was the eldest

of four children. His father headed public relations for New York

Bell Telephone. Although the family wasn't rich by Rye standards,

they belonged to the Apawamis Club, where young Dick played golf

and once met Babe Ruth in the shower room.

Sent to Catholic schools, Dick Cooley learned what he later

described as "the consequences of doing sinful things and ending up

in hell." He enrolled in Yale at age 16 and was a C student, more

interested in sports than studies. After struggling in a German

class, he looked for a major that didn't have a language

requirement and settled on industrial administration and

engineering. His mother barred him from philosophy courses.

"She did not want the materialism of Yale to make my religion

seem unimportant," he wrote in a 2010 memoir, "Searching Through My

Prayer List."

Playing end on the Yale football team meant conquering his

"physical fear of the game," he wrote, and "helped me face some of

the challenges and obstacles that came later."

World War II interrupted his studies. After pilot training, he

was sent to Europe in 1944. During a test flight over France, his

P-38 Lightning crashed. Although he managed to parachute to the

ground, the right-handed Mr. Cooley lost his right arm and spent a

year recuperating. He later repeatedly helped train other amputees

to ski and otherwise get on with their lives.

After he graduated from Yale in 1945, his father offered to send

him to Harvard Business School but he was eager to start a career

and declined, a decision he later regretted. "Charging ahead

somewhat impatiently was my style," he wrote.

He worked for a publishing company for three years, helping

manage the printing of magazines. Then he moved to San Francisco

and became a trainee at American Trust Bank, later acquired by

Wells Fargo. He rose rapidly there. Partly, he said, that was

because the bank had done little hiring during the Depression and

war years and so had few candidates to succeed its aging

leaders.

At 42, he was named CEO. He successfully expanded Wells Fargo

into southern California and built up a network of small foreign

offices from Paris to Tokyo. Those foreign offices generally didn't

perform well, he later said, blaming the "herd mentality" of

bankers for the 1970s fad of setting up overseas outposts.

At home, he had the embarrassment of a $21 million embezzlement

by a manager in the Beverly Hills office, discovered in 1981.

As he neared 60, Mr. Cooley felt he was burning out and noticed

"young lions nipping at my heels." He resigned from Wells in 1982

and became CEO of Seafirst Corp., a Seattle-based bank struggling

with losses on energy loans. Within a few months of taking charge

there, he agreed to sell Seafirst to Bank of America.

He also held board seats at the California Institute of

Technology, Rand Corp. and United Airlines.

In his later years, he qualified again as a pilot and flew his

own Beechcraft Bonanza around the country. He taught leadership

courses in an executive M.B.A. program at the University of

Washington. His style was to offer pithy advice -- such as "listen

more than you talk" -- and give examples from his business life. He

also brought in other executives and urged his students to quiz

them.

"He was extraordinarily humble and unassuming," said Bill Ayer,

a former CEO of Alaska Airlines who taught with Mr. Cooley at UW.

"If you didn't ask him about himself, he'd never tell you."

He continued golfing past 90 and quit only when he could no

longer swing his clubs.

His personal life was complicated. After having five children

with her, he divorced his first wife -- a decision he later blamed

on his selfishness and excessive focus on work. His second marriage

also ended in divorce, and his third wife died of cancer. In 2003,

he married the former Bridget McIntyre, who shared his love of

flying. His survivors include her, four children from his first

marriage, eight stepchildren, eight grandchildren, one great

grandchild and two sisters. A son, Sean Cooley, died of cancer in

2015.

Write to James R. Hagerty at bob.hagerty@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 30, 2016 12:06 ET (16:06 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

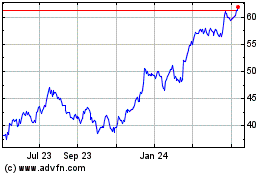

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

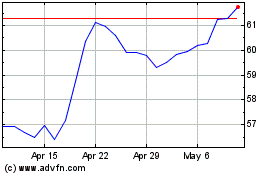

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024