By Emily Glazer

Wells Fargo & Co.'s board said it plans to claw back $41

million in compensation from Chairman and Chief Executive John

Stumpf as punishment for the bank's burgeoning sales-tactics

scandal, marking the first time since at least the financial crisis

that a major U.S. financial institution has forced its top

executive to relinquish previously earned compensation.

The bank's board moved to rescind pay for Mr. Stumpf and former

community banking head Carrie Tolstedt ahead of a hearing of the

House Financial Services Committee, Thursday. Wells Fargo said that

Ms. Tolstedt will forfeit unvested equity awards valued at $19

million and that she won't exercise "outstanding options" during an

investigation into the bank's sales practices.

Clawbacks, or their absence, became a big focus of a Senate

Banking Committee hearing last week. During his appearance before

that panel, Mr. Stumpf and the bank were roundly criticized for

firing 5,300 employees over five years, yet taking no action

against top executives.

The awards being forfeited by Mr. Stumpf represent about a

quarter of the total compensation he has accrued over his nearly 35

years at the bank, according to an independent analysis by

human-resources consultancy Overture Group LLC. Mr. Stumpf earned

total compensation of around $19 million in 2015.

The bank said that the $41 million is from Mr. Stumpf's unvested

equity awards. It also said that he would forgo salary during an

investigation and will not receive a bonus in 2016.

The closest a big-bank CEO has come in recent years to such a

clawback occurred at J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. That bank halved

annual compensation in 2012 for chief James Dimon to $11.5 million

from $23.1 million due to its London Whale trading scandal. But

J.P. Morgan didn't formally claw back compensation.

J.P. Morgan did impose the maximum pay clawbacks on three

traders involved with the debacle, which cost the bank around $6

billion. Ina Drew, the former bank executive who oversaw the unit

at the heart of the scandal, volunteered to return pay in line with

the maximum clawback.

Otherwise, there have only been sporadic instances of attempts

to recover pay on Wall Street, usually involving lower-level

employees.

Action on pay is again likely to be an issue before the House

panel. Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R., Texas), chairman of the financial

services committee, told reporters at a conference Tuesday that

Wells Fargo shareholders would be justified in calling for

compensation to be forfeited.

"If I was a shareholder, I'd be outraged if there weren't

clawbacks," Mr. Hensarling said. He promised to use his hearing and

a committee investigation to find out how a "fraud of this massive

scale took place" at the lender.

In a prepared opening statement for Thursday's hearing, Mr.

Stumpf didn't address issues related to pay, according to a copy of

the testimony reviewed by The Wall Street Journal. He did say the

bank would be accelerating its decision to end sales goals for

retail-banking employees by October 2016 instead of January 2017,

the date initially given when the change was announced earlier this

month.

Ms. Tolstedt became a point of focus at the Senate hearing

because she oversaw the bank's retail-banking operations during the

time in which regulators allege "widespread illegal" practices took

place. She stepped down from her role in July and was set to retire

at year-end. Wells Fargo said Tuesday that Ms. Tolstedt has now

left the bank.

Her total compensation, including accumulated stock and options

earned over her 27 years at the bank, could run to about $90

million, according to a letter Wells Fargo sent senators last week.

Ms. Tolstedt received total compensation for 2015 of $9.05

million.

Wells Fargo has been in the hot seat since news spread that as

many as two million unwanted or fictitious customer accounts were

opened by its employees to meet sales goals. The bank this month

entered into an enforcement action and paid a $185 million

settlement to two regulatory agencies and the Los Angeles City

Attorney's office.

In response to heated questions about Ms. Tolstedt's

compensation during the Senate hearing, Mr. Stumpf said that is a

matter for the board's human-resources committee. While Mr. Stumpf

is chairman of the board, he isn't a member of that committee,

which is led by Lloyd H. Dean, president and chief executive of

Dignity Health, a San Francisco-based not-for-profit health-care

system.

His answer, though, brought a rebuke from one senator. "The

board should have already acted to claw back those salaries," Sen.

Heidi Heitkamp (D., N.D.) said at the hearing. "If you had come

here and said, the board now is clawing back, these are the things

that we're doing...you would be in a lot better position sitting in

that chair right now."

The board last week tapped Shearman & Sterling LLP to advise

it on whether and how it should claw back pay from top executives,

The Wall Street Journal reported.

Wells Fargo, like other banks, has detailed clawback policies

and provisions. "Wells Fargo has strong recoupment and clawback

policies in place" in part to discourage its senior executives from

taking "imprudent or excessive risks that would adversely affect

the company," the bank said in its latest proxy statement.

Such provisions can be triggered by misconduct that does

reputational harm to the bank; improper or grossly negligent

failure, including in a supervisory capacity, to monitor or manage

material risks to the bank or business group; and a material

failure of risk management, among others.

In 2013, Wells Fargo agreed to enhance its clawback policy in

exchange for New York City pension funds dropping a related

shareholder resolution proposed by the city comptroller's office.

New York City pension funds own almost $500 million in Wells Fargo

stock.

Under the revised policy, bank directors can recover pay from

employees engaged in misconduct and from executives who supervised

them.

"This bank needs to regain trust from both the public and

investors, and clawing back profits from senior management would be

a step in the right direction," New York City Comptroller Scott M.

Stringer said in a statement.

The Wells Fargo sales-practices scandal has already rekindled

debate about clawbacks. Regulators earlier this year proposed

tighter restrictions on how Wall Street bankers are paid and are

finalizing the rules.

Among them is a requirement for the biggest firms to claw back

bonuses from employees engaged in misconduct that results in

significant financial or reputational harm or any fraud. Those

proposed rules would require banks to take back pay for wrongdoing

for at least seven years after the executive receives the

payment.

Among them is a requirement for the biggest firms to claw back

bonuses from employees engaged in misconduct that results in

significant financial or reputational harm or any fraud. Those

proposed rules would require banks to take back pay for wrongdoing

for at least seven years after the executive receives the

payment.

Bankers have resisted the proposals, saying they have already

tightened compensation standards and adopted voluntary clawback

policies.

Gabriel T. Rubin and Yuka Hayashi contributed to this

article

Write to Emily Glazer at emily.glazer@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 27, 2016 19:49 ET (23:49 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

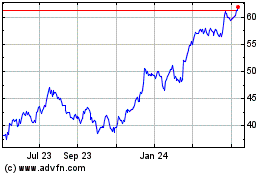

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

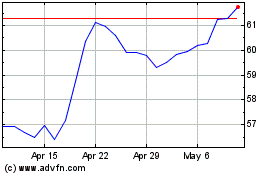

Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024