By Ryan Knutson

Not long after the 2000 merger that formed Verizon

Communications Inc., Denny Strigl rushed to Boston to talk wireless

employees out of joining a union.

"We fought it tooth and nail," said Mr. Strigl, who ran

Verizon's wireless operations until retiring in 2009. "There's a

mentality that builds up in a unionized workforce that pits the

union against its management. And that's not the kind of culture

that you want in a new startup."

The episode was one of many over the years in which Verizon

sought to keep unions out of its fast-growing wireless

business.

The result: the company has avoided work stoppages at operations

that employ about 75,000 and generated about two-thirds of its $132

billion in revenue last year.

Of the nearly 40,000 Verizon employees who went on strike April

13, only about 160 worked for the company's wireless unit.

And, as the company's landline business has shrunk, so too has

unions' influence on it.

Last week, the company made what it called its best and final

contract offer. Union leaders said the strike would continue.

"We state upfront, if you want to join a union you can join a

union," said Marc Reed, Verizon's chief administrative officer. "At

the end of the day, people have chosen not to."

Part of the reason is history. Verizon's landline business

sprang out of the Baby Bells, and has been unionized for decades,

while its wireless division was formed in 1995 as a separate joint

venture. The wireless unit has contracted out most of its

construction work and many of its employees are retail clerks.

The number of Americans working in the telecom industry has been

shrinking -- to about 880,000 in 2015 from more than a million a

decade ago -- but union jobs have disappeared even faster.

About 13% of U.S. telecommunications workers were union members

last year, down from 21% in 2005, according to the Labor

Department. The last strike of the Ma Bell era, in 1983, involved

roughly 675,000 workers.

AT&T Inc. is the only major U.S. carrier with a significant

union presence in its wireless division. More than 125,000, or

about 45% of AT&T's overall workforce, are unionized.

None of Sprint Corp.'s roughly 30,000 employees are union

members. T-Mobile US Inc. has about 30 unionized workers out of

50,000. All four carriers rely on contractors to build and maintain

cell towers.

The Communications Workers of America has tried several times to

penetrate Verizon's wireless workforce.

In 2000, when about 85,000 landline workers went on strike, the

union pushed for an arrangement called card-check neutrality;

Verizon agreed, helping to end the strike after 18 days.

Under such deals, a company agrees to automatically recognize a

union if a majority of workers sign cards authorizing one to

represent them.

The card-check system was used by unions to expand at

AT&T.

At Verizon, the two sides fought for more than a year about the

details of the deal. By the time the issues were finally resolved,

the union says it didn't have much time to organize before the

agreement expired.

"That agreement was totally useless," said Ed Sabol, a

now-retired CWA official who tried to organize the Verizon workers.

"The employees never had the ability to make that decision free of

incredible fear."

Mr. Strigl said it was employees who made the choice. "We worked

hard to give employees the pay and benefits that didn't cause them

to want to have to join the union," he said.

The 350-person call center near Boston where Mr. Strigl spoke

with wireless employees was closed in 2001 as part of an overhaul

to Verizon's call center operations.

Verizon settled allegations that year by the CWA that it

threatened workers. The company neither admitted nor denied any

wrongdoing.

"Runaway call centers send a message to everyone else: You try

to organize a union, and you can kiss your job goodbye," said Steve

Early, a retired CWA official.

The CWA says it was working in 2004 to win over wireless call

centers in Orangeburg, N.Y., and in Morristown, N.J., with about

1,700 employees when Verizon moved the operations to less union

friendly Southern states.

The company said the old locations couldn't accommodate the

necessary growth, and that other states offered better business

incentives.

The carrier offered displaced employees a package including

$10,000 to relocate.

Mr. Reed, Verizon's administrative chief, said the call centers

were moved for business reasons, and not because of the union.

"We would rather be able to deal directly with our employees and

communicate the way in which our culture says, as opposed to have

to follow some bureaucratic legacy approach to dealing with

employees," Mr. Reed said.

The union has a toehold at Verizon Wireless. About 100 wireless

technicians joined the CWA more than a decade ago.

In 2014, employees at six Brooklyn, N.Y., stores and one in

Everett, Mass., joined CWA. Those employees are still negotiating

with Verizon for their own contract.

Bianca Cunningham, a worker who helped organize the Brooklyn

stores, says without a union, it can take years to earn meaningful

wage increases. "We were just trying to fight for ourselves and see

some changes," she said.

In September, Ms. Cunningham was fired.

Verizon told the National Labor Relations Board she was

terminated because of her "failure to be honest and forthcoming"

during a code-of-conduct investigation.

Ms. Cunningham claimed it was because she helped organize

workers.

Regional NLRB director James Paulsen filed charges against

Verizon in the case, which is pending before an administrative law

judge.

Write to Ryan Knutson at ryan.knutson@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 01, 2016 20:19 ET (00:19 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

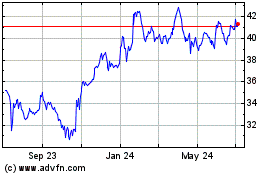

Verizon Communications (NYSE:VZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

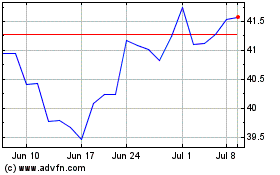

Verizon Communications (NYSE:VZ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024