MUMBAI—When Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced on prime time

TV Tuesday that bank notes making up almost 90% of the value of

currency circulating in Asia's third-largest economy would become

worthless paper within hours, he stunned a cash-loving nation.

He also drove bankers back to the office.

"It was like watching a bomb drop," said Rajnish Kumar, a

managing director at State Bank of India Ltd., whose job includes

running the network of branches and ATMs at the country's largest

lender. "I rushed back to the bank and set up the war room."

India will replace its largest currency denominations with newly

designed ones, in a move aimed at curbing graft and clearing the

economy of counterfeit money, whose tight time frame is creating

challenges for banks and households alike.

Mr. Kumar needed to make sure that by Thursday at noon he would

know how many 500- and 1,000-rupee notes were left in the SBI

network, including the bank's 16,700 branches and its 55,000 cash

dispensers.

In a nation where cash is king, Mr. Modi's surprise move is

aimed at purging the economy of piles of cash that originate in

activities that are either illegal or unknown to the taxman. By

some estimates, India's black economy is worth half of the

country's gross domestic product.

The decision, however, is likely to put the economy under severe

strain in the short term, economists say, because even legitimate

business is mostly conducted in cash. UBS economists said in a note

that discretionary consumption, gold and property demand will

suffer the most.

The massive pullout of 22 trillion notes—worth $214 billion, or

14% of GDP—appears a logical step after efforts by Mr. Modi to make

the world's second-largest country less dependent on cash and its

population more engaged with the banking system.

On Wednesday, people throughout the country had only a limited

number of smaller bills so they used them wisely. In Delhi and

Mumbai, India's largest cities, the tiny businesses that make up

the bulk of the country's retail and service industries were

starved for customers as the small change needed for small

transactions, like a rickshaw ride or a bridge toll or shot of

masala tea just wasn't available.

While some crucial businesses, including gas stations and

hospitals, were still allowed to accept older big notes on

Wednesday, they were useless elsewhere. Some shoppers in Delhi went

from store-to-store trying to find a way to shop with their

leftover 500 rupee notes but none was willing because of the

uncertainty.

With Mr. Modi's PMJDY, or Prime Minister's People Money Scheme,

launched soon after he swept into power in the 2014 election, the

government sponsored the opening of more than 254 million accounts

in two years.

But banks—most of which are government-controlled—have

complained that the operation represents a net cost because most

customers kept their accounts at a zero balance.

The government has since adopted measures to make sure that

money would flow through the system. An increasing number of

subsidies, including aid to purchase cooking gas and scholarships,

are now directly credited to bank accounts, and analysts see

Tuesday's move as a further step to make the economy less cash

intensive.

Mr. Kumar spent most of the night working out how to drive the

notes back to the 1,896 currency chests, or centers where it holds

the cash it distributes to its branches throughout the country,

with just 38 hours to set up contingency plans.

"The main challenge is to go get the notes wherever they're

lying in our system," said Mr. Kumar. He declined to comment on the

total volume of notes—or the value—that the SBI was storing in its

network at the time of Mr. Modi's announcement.

Mr. Kumar said that since Tuesday night he made sure that enough

staff would be recovering the money stored in ATMs, and said that

the staffing of the bank's customer service was boosted to answer

clients' queries. Branches will stay open longer than usual,

closing at 6 p.m Thursday instead of 5 p.m., a bank spokesman

said.

Smaller banks face a different set of challenges, but not less

pressure.

"We bankers are not magicians," said Murali Natrajan, managing

director of DCB Bank, a small Mumbai-based lender. "It's a lot of

stuff to do between now and tomorrow."

Mr. Natrajan said the main challenge for DCB was to create a

system that would prevent people from showing up at a bank

branch—or at multiple branches—to change old notes into new ones

for an amount exceeding 4,000 rupees per person, the limit set by

the central bank to make sure large amounts of cash stashed away

would come to the surface.

"I don't think any bank is geared up to do that at the moment,"

Mr. Natrajan said.

The government's abrupt move immediately appeared as a boost for

e-payment companies.

"They're trying to make cash inconvenient, and the more

inconvenient cash becomes the more business we get," said Vinay

Kalantri, the founder and managing director of The Mobile Wallet,

an electronic payment company. "Today is a good day for us."

Eric Bellman contributed to this article.

Write to Gabriele Parussini at gabriele.parussini@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

November 09, 2016 12:15 ET (17:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

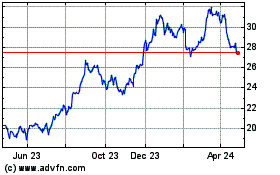

UBS (NYSE:UBS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

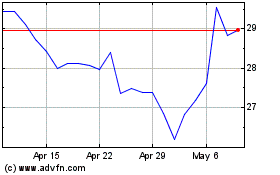

UBS (NYSE:UBS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024