Pittsburgh is running out of time to solve a severe pension

problem.

If the city's retirement system, which currently has only 28% of

the assets it needs to cover its obligations, cannot bring its

funding up to 50% on Dec. 31 -- meaning the addition of $220

million -- the state will take it over.

That could result in painful consequences for local residents,

such as loss of services and higher taxes to build up the pension

fund.

Municipal bond analysts say that such a state takeover of a

local pension system is rare. But they see more of them ahead as

cash-strapped cities and towns struggle with revenues falling short

of rising liabilities.

"They're all undergoing the same pressure in terms of reduced

revenues and increased pressure on public spending, during a time

while it feels like the economy has stabilized, it doesn't feel

like it's recovering quickly enough to refill the revenue budgets

where they were a couple years ago," said Mike Dawson, investment

officer at MFS Investment Management in Boston.

Pennsylvania legislators last year enacted a law requiring that

Pittsburgh's pension system be brought up to 50% funding as of the

end of 2010 or be turned over to state officials. Pittsburgh's

pension system is the most underfunded among systems in the state

and is likely among the most underfunded in the country, according

to municipal analysts.

Obligations are estimated to be roughly $990 million. Current

assets are about $272 million, according to the most recent

actuarial report.

"Once you get below 50%, pretty much everyone in the business

agrees you're in a death spiral," said James McAneny, executive

director at the Public Employee Retirement Commission, which

monitors more than 3,000 local pension plans in Pennsylvania.

"Nobody thinks you're going to earn your way out of it."

State officials will lay out parts of their takeover plan

Thursday, including how much they would require the city to

increase its annual contribution to its retirement system. Some in

the city hope that the shock of a large number may spark renewed

negotiation and urgency to come up with a different solution.

The path leading to Pittsburgh's crisis is far from unique. The

city, the state's second-biggest with about 300,000 residents, had

for years failed to fund its pensions adequately. Instead, it

relied on overly optimistic forecasts of investment returns to

cover the generous promises it made to its employees.

Pittsburgh officials this year and last year put around $60

million into the pension fund. But during the decade before 2009,

the annual contributions were around $40 million to $45 million,

said city controller Michael Lamb. Meanwhile, the system pays

retirees $82 million a year.

Compounding the problem, retirees now outnumber active workers

contributing to pensions by one-third, said Cathy Qureshi, the

city's assistant director of finance.

The pension fund also assumes an 8% annual return on its

investment, which several analysts called unrealistic. The Standard

& Poor's 500-stock index has risen 6.9% so far this year, while

the Barclays Capital U.S. Aggregate Bond Index has gained

8.54%.

To shore up the pension fund, Mayor Luke Ravenstahl for nearly

two years advocated a long-term lease of parking garages and meters

by private investors. But two weeks ago, the City Council rejected

the top bidder, a team led by J.P. Morgan Asset Management and LAZ

Parking, which offered about $452 million for a 50-year lease.

Instead, the council put forth its own alternative: a plan that

called for the parking authority to sell bonds to buy city-owned

parking assets for $220 million -- money the city would use to

boost the pension to 50% funding.

But that proposal, which Ravenstahl characterized as "fiscally

irresponsible," was stymied by the parking authority board, which

last week refused to hire a consultant to study it.

As difficult as it appears, getting to that 50% threshold would

prevent more stringent measures. Under state control, the fund

would have to reduce its investment-return forecast to 7.5%

annually.

The lower rate could increase the amount the city would have to

contribute to the plan to about $72 million a year, city

administration officials anticipate. That's about 16% of the city's

$450 million budget.

Qureshi said the mayor wants to avoid raising taxes but reduced

services would be likely under a takeover.

The prospect of a state straitjacket should trouble investors,

Paul Brennan, portfolio manager at Nuveen Asset Management, said.

Mandatory payments to the state could reduce the city's financial

flexibility -- "not necessarily a good thing for bond holders,"

Brennan said.

Other analysts, however, said that a state takeover could spur

tough choices that create significant reforms in the long-term.

Often, "there is not political will on the local level," said

Adam Weigold, portfolio manager at Eaton Vance. "But if you have

the state forcing you to make decisions, the decisions actually get

made."

-By Romy Varghese, Dow Jones Newswires; 215-656-8263;

romy.varghese@dowjones.com.

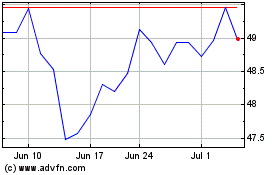

Sun Life Financial (NYSE:SLF)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

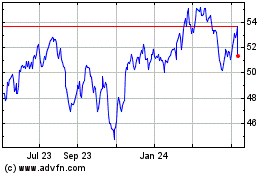

Sun Life Financial (NYSE:SLF)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024