MADRID—Spaniards set to lose their banking jobs in the coming

months might fault their bank bosses. They should save some blame

for Mario Draghi.

Mr. Draghi, the head of the eurozone's central bank, has

repeatedly cut interest rates to jolt Europe's economic growth.

Last Thursday he said the European Central Bank was willing to use

"all instruments available," including additional rate cuts, to

spur expansion.

While some consumers and businesses have benefited from lower

payments on their loans, subzero rates have chipped away at banks'

profitability. In Spain this has forced banks to cut costs.

Banco Santander SA, the eurozone's largest lender by market

value, announced this month that it is closing 450 smaller bank

branches and cutting up to 1,660 positions in Spain this year,

according to an internal staff memo and a person close to the

bank.

Spain's No. 3 bank, CaixaBank SA, said it has reached early

retirement agreements with up to 484 employees to trim salary

expenses. Small regional lender Liberbank SA has plans to shutter

up to 25% of its bank branches during the next two years and peer

Banco CEISS has announced it will cut up to 1,120 jobs.

When major Spanish lenders report their first-quarter earnings

this week, analysts expect an overall weak set of results—and

further impetus for slashing costs.

Executives at Spanish banks are seasoned at closing offices and

cutting staff. A property boom went bust in 2008, forcing dozens of

weaker lenders to close, merge or be purchased. With help of a

European Union bailout, the banking sector recovered and Spain grew

out of a recession. But now the banks face gale-force

headwinds—negative interest rates, lackluster demand for home

mortgages, muted returns on business loans—that show no signs of

subsiding.

"Spain's financial sector is confronting a period of great

change," Santander Spain country head Rami Aboukhair wrote in a

memo to employees explaining the branch closures and layoffs. "The

current economic context, greater regulatory requirements and the

evolution of client behavior toward new technology makes it

necessary to move more quickly in our commercial

transformation."

Another factor in branch closures in Spain is the shifting

habits of clients, bank executives say. Younger Spaniards in

particular shun visits to physical offices in favor of online

clicks to take out a consumer loan or make a payment.

Overall, however, the cutbacks are aimed primarily at offsetting

a long decline in the banks' earnings. Their net interest income

and fees fell by 31% from December 2009 to December 2015, while

operating costs declined by 12.5%, according to data from Spain's

central bank.

"Profitability is under a lot of pressure," Citigroup analyst

Stefan Nedialkov said. That's "the urgency that is making the banks

focus more on costs now. Digital is definitely a factor, too, but

it's not the driving factor."

Spanish banks cost-to-income ratios "were always best in class,"

Mr. Nedialkov said. "But now top line growth isn't there," he

added, and that is forcing banks to rethink a model that

prioritizes a physical presence in communities throughout

Spain.

Spain has more branches per person than any other country in the

EU except Cyprus, according to ECB data through 2014. Even after a

26% decline in branches between 2010 and 2014, Spain has around

three times as many bank branches as the U.K.

"We will see less capillarity in the financial system in Spain"

in coming years, Banco de Sabadell SA Chief Executive Jaime

Guardiola told journalists on Friday. "Progress has already been

made."

Bank profits have been hit especially hard by a decline in the

euro interbank offered rate. Euribor, as the benchmark is known,

underpins most Spanish mortgages, which fluctuate when the interest

rate changes. The 12-month Euribor has plummeted from 2.12% in

April 2011 to around -0.01 this month.

Starting several years ago, most Spanish banks included

interest-rate floors in their mortgage contracts—a limit on how far

borrowers' monthly payments could fall. But Spanish courts have

ruled that many of those mortgage floors weren't spelled out

clearly enough to consumers and ordered them to be removed,

triggering a drop in bank revenue.

Spain's economy has posted strong growth in the past two years,

but demand for mortgages remains historically weak as borrowers

choose instead to pay off existing debt. That has forced Spanish

banks to rely more on business loans. But they all did so en masse,

driving down the interest rates they charge, another hit to

profits.

Low interest rates means that banks, for instance, also pay

customers less for their deposits. But those lower funding costs

haven't been enough to offset the other negative trends.

In May of last year, Santander introduced a new higher interest

checking account in Spain. It was a costly launch, at least in the

short term, for Santander itself as well as for rivals who tried to

match the offer.

That has been a further drag on Spanish banks' profits.

Write to Jeannette Neumann at jeannette.neumann@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 26, 2016 06:45 ET (10:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

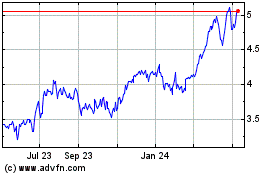

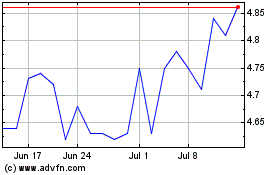

Banco Santander (NYSE:SAN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Banco Santander (NYSE:SAN)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024