Johnson Controls Inc. is set to become the latest American

company to move abroad in search of tax savings—and to do so on the

coattails of the dismantled Tyco empire.

Johnson Controls, an industrial-systems and battery maker whose

Milwaukee roots stretch back to 1885, said Monday it will merge

with Tyco International PLC and take on Tyco's Irish tax address.

The deal, valued at roughly $14.4 billion, is a so-called inversion

that should allow Johnson Controls to lower its tax rate over

time.

The merger—the first fresh megadeal of 2016—highlights the

self-perpetuating nature of inversions, as American companies that

move their legal homes abroad create opportunities for others to

follow. Those deals, in turn, further challenge U.S. regulators

trying to stanch the exodus of tax dollars overseas.

Tyco was an early expat, decamping first to Bermuda in 1997 and

finally settling in Ireland. Over the years, it spawned a crop of

spinoffs and subsidiaries that inherited one of Tyco's most

valuable assets: its foreign tax address. When M&A activity

rebounded after the financial crisis, those new firms became major

players in a wave of cross-border, tax-lowering deals, enabling

American companies with about $70 billion in annual revenue to slip

out of the U.S. tax net.

Tyco paid 12% of its profit in taxes over the past three years,

versus an average 29% by Johnson Controls, according to S&P

Capital IQ. Johnson Controls said its effective tax rate before

certain items was around 19% over the past two years ended Sept.

30.

In some ways, Monday's deal has its roots in the accounting

scandal that rocked Tyco more than a decade ago. After CEO Dennis

Kozlowski's conviction, breakup artist Edward Breen took over with

a mandate to pare Tyco's sprawling empire, which at the time

included everything from pharmaceuticals to burglar alarms. Many of

the resulting offshoots have become targets for U.S. companies

seeking inversion partners, while others have used their lower tax

rates to become consolidators, buying U.S. assets—which on average

pay higher rates—and squeezing tax savings that way. In 2012, Tyco

sold its pump-and-filter business to Pentair PLC, an inversion that

moved the U.S.-based company abroad. Last summer, Pentair bought

U.S.-based Erico Global for $1.8 billion.

Tyco's health-care business was eventually hived off into two

new companies, both of which have enabled tax-lowering

combinations. A more than $40 billion takeover of Covidien PLC,

which housed Tyco's medical-device business, allowed U.S.-based

Medtronic Inc. to invert last year.

Meanwhile, Mallinckrodt PLC, Tyco's legacy pharmaceuticals arm,

has used its lower tax rate to advantage as an acquirer. In its 2½

years as a stand-alone company, Mallinckrodt has spent nearly $11

billion on takeovers of higher-taxed U.S. drug assets.

Monday's deal also underscores the snowball effect of

inversions. As such deals pile up in a particular industry, they

enable more—and—bigger companies to follow suit. That is because

U.S. rules require foreign targets to be of a certain size relative

to their buyers.

Witness what happened in the pharmaceutical industry. In 2013, a

New-Jersey based drug company called Watson Pharmaceuticals

inverted by buying a small Irish rival. After a series of deals,

the resulting company—Allergan PLC, with a $117 billion market

value—is big enough to serve as the inversion partner for Pfizer

Inc., in what would be the largest corporate expatriation ever. The

deal is pending.

And if a combined Pfizer-Allergan spins off its generics

business, as is widely expected, it would create a potential

inversion partner for a host of big U.S. drugmakers.

The Johnson Controls-Tyco deal is at least the 12th inversion

pursued by American companies since the U.S. Department of the

Treasury moved in September 2014 to curb these deals, according to

a Wall Street Journal review. That is roughly the same number in

the 16 months before the move.

"This is yet another example of why we need tax reform to keep

our employers and jobs in America, rather than encouraging them to

move overseas," said House Speaker Paul Ryan (R., Wis.), who has

pushed for a tax overhaul that would, among other changes, lower

the rates U.S. companies pay. Johnson Controls is the largest

public company based in Mr. Ryan's home state of Wisconsin. The

company was founded 131 years ago by a Milwaukee professor who had

received a patent for the first electric thermostat.

The deal is likely to reignite a campaign-trail debate. Sen.

Bernie Sanders, a Democratic presidential candidate said the deal

would be "a disaster for American taxpayers" and denounced

"corporate deserters."

Johnson Controls and Tyco structured their deal to reap maximum

tax benefits. By giving Johnson Controls investors less than 60%

ownership of the combined company, they sidestep regulations aimed

at more-lopsided combinations that might have made the deal less

attractive.

"Below 60 [%] is the Holy Grail of inversion planning," said

Omri Marian, a tax law professor at the University of California,

Irvine.

Inversions let U.S. companies lower their tax rates over time by

giving them ways to shift profit out of the U.S. and move cash

easily from low-tax jurisdictions back to shareholders.

Johnson Controls Chief Executive Alex Molinaroli said the merger

wasn't tax-driven and pointed to the roughly $500 million in annual

savings expected to be wrung from combining the businesses. But, he

said in an interview Monday, "we definitely get some benefits, so

we'll take those benefits."

Back to 1997, when Tyco moved to Bermuda by acquiring

home-security firm ADT, it was one of the earliest inversions.

After Bermuda came under fire as a tax haven, the company moved in

2008 to Switzerland, and to Ireland in 2014, after Switzerland

enacted tougher rules around CEO pay and corporate governance.

Just last week, Tyco settled a long-running dispute with the

Internal Revenue Service for up to $525 million, far less than the

government had sought. That controversy stemmed from what's known

as earnings stripping, the practice of using internal company

transactions to concentrate tax deductions in the U.S. and profit

in low-tax countries.

Dana Mattioli contributed to this article.

Write to Liz Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com and Richard Rubin at

richard.rubin@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

January 25, 2016 20:15 ET (01:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

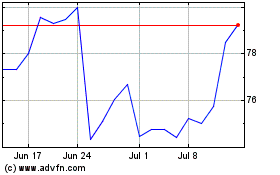

Pentair (NYSE:PNR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Pentair (NYSE:PNR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024