BRASÍ LIA—Eduardo Cunha, leader of the lower house of Brazil's

congress, had a hectic day on Dec. 15. Federal police raided his

home around 6 a.m. seeking evidence he had received kickbacks in a

wide-ranging embezzlement scandal relating to the state oil company

Petrobras.

Hours later he was in Congress, impeccably dressed in a blue

suit, vowing to move forward with his top legislative issue, a

motion to impeach Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff for allegedly

using accounting tricks to mask deficits.

"I wake up at 6 a.m. My door is always open. I have no problem

with this," Mr. Cunha, a talkative former radio host, told

reporters that day.

Mr. Cunha is poised to make history by bringing the impeachment

vote against Brazil's president to a floor vote as soon as Sunday.

If it passes by two-thirds, she faces a trial in the Senate. Ms.

Rousseff would be the second president impeached since Brazil's

1985 return to democracy, deepening political uncertainty in a

country that also faces a severe economic contraction.

All the while, Mr. Cunha's own legal battles continue. Brazil's

attorney general brought charges of corruption and money-laundering

against him last summer, adding new allegations a month ago. Swiss

authorities have closed four bank accounts they say were his. The

attorney general says bribe money was used to pay Cunha family

credit-card bills, including $156,000 in the six months through

January 2015.

Mr. Cunha has denied any wrongdoing. He has said the Swiss

accounts weren't his, and any money he spent was earned legally. He

declined to be interviewed.

The sweeping Petrobras scandal, in which businessmen and

politicians stand accused of diverting oil-company money to

themselves and political parties, with 84 convictions so far, has

spurred hopes that a country long beset by corruption may be

turning an ethical corner. That the legislator overseeing

impeachment is also facing charges suggests how difficult that will

be, in a country where the roots of corruption are deep.

Ms. Rousseff has said she did nothing wrong. Her aides contend

Mr. Cunha supported impeachment to divert attention from himself.

They note that after months of bottling up impeachment motions, Mr.

Cunha decided to move one forward just hours after Ms. Rousseff's

party said it would no longer vote to protect him from

prosecution.

A poll a week ago showed 61% of Brazilians think Ms. Rousseff

should be removed from office; 77% think Mr. Cunha should be.

According to a nonprofit called Transparê ncia Brasil, 60% of

Brazil's federal legislators have been convicted or are under

investigation, for crimes ranging from corruption to electoral

fraud to assault. The president of the Senate, Renan Calheiros, is

a focus of numerous lines of investigation in connection with the

Petrobras scandal; he denies any involvement. Ex-President Luiz Iná

cio Lula da Silva is also under investigation, suspected of being

the real owner of a ranch and a beach-front apartment registered to

third parties, which he denies.

Many Brazilians are caught between satisfaction at seeing

leaders held accountable and despair that so much of the political

class is implicated.

"I want Dilma gone, but that won't change everything. Do you

know why? The person next in line after her is terrible, and the

person after him is worse, and so on," said Thiago Vieira, a young

financial analyst who stood in a sea of protesters chanting "Dilma

Out!" in Sã o Paulo on March 13.

The impeachment charge against Ms. Rousseff doesn't involve

Petrobras. The motion alleges she violated federal budget laws by

using loans from state-owned banks to mask the size of the

government's budget deficit.

An electoral court, however, is investigating whether Ms.

Rousseff's 2014 re-election campaign was funded partly with

kickbacks from the Petrobras scandal. She says it wasn't. Public

support for Ms. Rousseff's ouster has surged as the corruption

allegations have widened and the economy tanked. Many blame Ms.

Rousseff for allowing corruption to flourish, noting she was the

Petrobras chairwoman while much of the scandal unfolded. She says

she was unaware of any illegal activities.

Ms. Rousseff's replacement if she were removed would be Vice

President Michel Temer from Mr. Cunha's PMDB party, which shared

power with the president's Workers' Party before splitting off in

March. Mr. Temer is included in the electoral court investigation

of whether bribe money funded Ms. Rousseff's 2014 campaign; he

denies that it was. Mr. Temer stepped down as leader of the PMDB

this month after a Supreme Court justice made a preliminary ruling

that any impeachment of Ms. Rousseff must consider him, too.

Mr. Temer's successor as party chief, Sen. Romero Jucá , is

under investigation in connection with the Petrobras scandal. He

denies having anything to do with it.

"My God in Heaven, this is our alternative leadership?" said

Supreme Court Justice Luis Roberto Barroso on March 31 in a meeting

with law students that he didn't know was being recorded. "The

problem with our politics at this moment is the lack of

alternatives. There is nowhere to run."

Third in line to the presidency is Mr. Cunha, 57 years old. An

economist by training, he broke into politics campaigning for

Fernando Collor, who won the presidency in 1989 and named Mr. Cunha

to run Rio de Janeiro's phone company. Mr. Collor was impeached for

corruption in 1992.

A religious conservative, Mr. Cunha began hosting a radio show

decrying abortion and same-sex marriage. He often exclaimed, "The

people deserve respect!" In 2003, he won a seat in the lower house

of Congress with Evangelical support.

His backers there describe Mr. Cunha as a dusk-to-dawn

negotiator, often using an iPad or cellphone to send What's App

messages to a network of allies. His knack for raising funds and

delivering votes won him support among dozens of lawmakers in

several parties, analysts say.

In February 2015, he became president of the lower house, called

the Chamber of Deputies. By then, the Petrobras scandal was

claiming prominent businesspeople, and voters were calling for Ms.

Rousseff's removal.

Mr. Cunha appeared invincible. Brazilian news magazines compared

him to Frank Underwood, the scheming politician played by Kevin

Spacey in the drama "House of Cards."

In March 2015, however, the Supreme Court gave the attorney

general the go-ahead to investigate Mr. Cunha and dozens of other

politicians. Mr. Cunha made an hourlong speech in Congress calling

the investigation a joke. Legislators applauded loudly.

By August, the attorney general had brought charges against Mr.

Cunha, alleging that from his position in Congress, he pressured

executives for bribes in exchange for amendments favorable to their

businesses. He has denied that.

The main charges related to the Petrobras matter, which many

call Brazil's biggest ever corruption scandal. The oil company has

acknowledged losses of $17 billion from it, including from

embezzlement and money-losing projects.

The indictment alleged that in 2006, Mr. Cunha helped

orchestrate a $40 million bribe in exchange for two contracts to

build floating oil platforms for Petrobras. The charges said a

broker who represented South Korean shipbuilder Samsung Heavy

Industries and its partners paid the bribe out of a huge fee he

charged his clients. The broker opened a running tab for Mr. Cunha

at a business-jet charter firm, the charges said.

Mr. Cunha began opening Swiss bank accounts under various names,

such as "Triumph," the Brazilian charging documents said. They said

investigators have traced oil money to these accounts, including a

kickback from an executive appointed to Petrobras by the PMDB.

The broker who represented Samsung Heavy Industries became a

cooperating witness last July 2015, according to Brazilian

prosecutors. He told investigators Mr. Cunha had received a $5

million cut of bribes paid in the oil-platform contracts, which was

paid mostly to a Petrobras executive and a money launderer,

according to the indictment. It said the broker, Julio Camargo,

described a meeting he said he had with Mr. Cunha to discuss the

scheme at an office in the Leblon district of Rio de Janeiro.

Mr. Cunha summoned Mr. Camargo's defense attorney before a

congressional commission. The attorney, Beatriz Catta Preta, never

appeared. She told a television journalist she had received "veiled

threats." She dropped Mr. Camargo as a client and closed her law

practice.

"After everything that's happening, and to ensure the safety of

my family, of my children, I decided to end my career in the law,"

she said in a TV interview. Ms. Catta Preta couldn't be reached for

comment. Mr. Camargo's new lawyer didn't return a message left with

his assistant.

The following month, August 2015, Brazil's attorney general's

office brought its charges against Mr. Cunha. According to the

charges, the bribe arrangement hit a snag in 2011, stopping the

payments, which were meant to come in installments. Mr. Cunha

responded by starting a congressional corruption investigation of

Samsung Heavy Industries' contracts, the charging document said,

and as a result of this pressure tactic, the remaining bribe

installments were paid.

The document said that at a time when Mr. Cunha's annual income

was around $120,000, he took his wife and daughters for a New

Year's 2013 trip to Miami—staying at the five-star Perry Hotel,

spending around $1,000-a-pop dining at places like Joe's Stone

Crab, and running up a credit-card bill of $42,000 in nine

days.

In February 2015, he flew to France and spent $8,000 at a

menswear boutique and $16,000 bill at the Plaza Athé né e hotel,

another charging document said.

Mr. Cunha has denied receiving any kickbacks or bribes. Samsung

Heavy Industries, which hasn't been charged, didn't respond to

requests for comment.

(MORE TO FOLLOW) Dow Jones Newswires

April 15, 2016 15:45 ET (19:45 GMT)

Though Brazilians facing such charges normally would be

arrested, Mr. Cunha hasn't been. An immunity provision in Brazil's

constitution says lawmakers can be arrested only if Congress or the

Supreme Court sanctions the move.

Another provision says they can be tried only by the country's

Supreme Court. Together, the rules shield legislators from most

prosecutions. The bulk of the seven-dozen Petrobras convictions

have been against businesspeople, not politicians.

Last fall, critics of Mr. Cunha in Congress attacked his

immunity through an inquiry by an ethics commission. The legislator

in charge was Fausto Pinato. On the night of Nov. 12, according to

a police report filed by Mr. Pinato and his chauffeur, two

motorcyclists approached the driver and said, "Ask your boss

whether he wants to go to heaven or whether it is better to

collaborate with the situation. He has a beautiful daughter, a

beautiful wife, a nice brother…"

A spokesman for Mr. Pinato said he doesn't know who threatened

him and isn't accusing Mr. Cunha, who says he had no involvement.

Mr. Pinato is no longer on the ethics commission because he changed

parties.

On Dec. 2, the leader of Ms. Rousseff's party in the lower house

of Congress announced the party would vote to strip Mr. Cunha of

his immunity from prosecution.

Later the same day, Mr. Cunha said he was moving forward with

impeachment proceedings against Ms. Rousseff.

In the previous months, Mr. Cunha had blocked 27 motions for

impeachment. Asked by reporters whether the Rousseff party's

position against him had prompted his switch, he said no, his

switch on impeachment was a technical decision based on the large

number of motions reaching his desk.

Brazil's attorney general this year asked the Supreme Court to

lift Mr. Cunha's immunity. The court hasn't ruled.

What the court did do, in March, was to accept charges the

attorney general filed last summer. That made Mr. Cunha officially

a defendant. He still has immunity from arrest.

The lead prosecutor in the Petrobras case, Deltan Dallagnol,

calls for an overhaul of rules such as legislators' immunity. He

says corruption runs so deep that even the dozens of convictions in

the Petrobras investigation won't root it out.

"If we want a country without corruption and impunity, we have

to alter the institutions," he said at a conference.

Mr. Cunha's first political patron, ex-President Collor,

returned to government 15 years after his impeachment. He was

elected to the Senate and put in charge of an ethics committee.

Last year, federal police began investigating Mr. Collor in

connection with the Petrobras scandal. Raiding his home, they found

a Lamborghini, a Porsche and a Ferrari. His spokesman says he is

innocent.

The attorney general brought charges, which the Supreme Court,

so far, hasn't accepted. In the Senate, Mr. Collor will be among

those voting on Ms. Rousseff's impeachment, if it passes the lower

house.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 15, 2016 15:45 ET (19:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

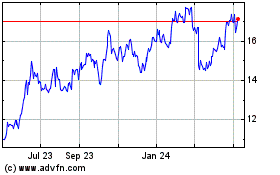

Petroleo Brasileiro ADR (NYSE:PBR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

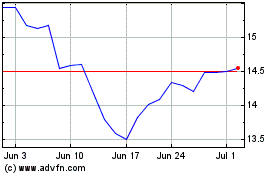

Petroleo Brasileiro ADR (NYSE:PBR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024