By Mike Esterl

To watch the heat rising on the soda industry, take a look at

San Antonio.

Coca-Cola Co., PepsiCo Inc. and Dr Pepper Snapple Group Inc.

have been pouring millions of dollars into fitness and health

programs in the Texas city, where about two thirds of adults are

overweight or obese and the diabetes rate is roughly twice the

national average. Their message: Good health is about exercise, not

just fewer calories.

Those efforts, begun in 2012, paid a big dividend last year when

San Antonio's city council balked at a public-education campaign

proposed by the city's health director that aimed to reduce soda

consumption. Several council members argued soda was being singled

out unfairly; some said the effort smacked of a "nanny state."

Then, after it looked like the issue was going away, Bexar

County--which includes and surrounds San Antonio--started to issue

its own warnings about soda. The countywide campaign--called "Is

Your Drink Sugar-Packed?"--has launched a website and distributed

more than 5,000 posters and fliers since June. Three digital

billboards began running the slogan last week and organizers plan

to advertise on television. "You wouldn't eat 16 teaspoons of

sugar. So why drink them?" says a campaign pamphlet, referring to

the amount of sugar in a 20-ounce soda bottle.

The reversal highlights one of the soft drink industry's biggest

challenges: constantly fighting the perception that soda is really

bad for you. No matter how much money it spends on research or

argues that exercise lowers obesity, the industry is playing a

never-ending game of Whac-A-Mole. When it beats down critics in one

place, they pop right back up in another.

Chicago has received millions of industry dollars for health and

fitness programs in recent years, but that didn't stop the chairman

of the city council's health committee from proposing a

penny-per-ounce tax on sugary drinks in July. In Minneapolis,

another past recipient of grants, the city's health department

launched a "Rethink Your Drink" campaign this summer. San Francisco

officials voted in June to require health warnings on sugary drink

advertisements, months after the industry spent heavily to defeat a

special tax.

William Dermody, vice president of policy at the American

Beverage Association, said the industry opposes campaigns "not

supported by science" and that "no single food or beverage uniquely

causes obesity." Coke spokesman Dan Schafer said the industry

"consistently opposes efforts that target one product or one

category or that attack our products in sensational ways."

Yet when beverage companies try to defend soda "there's inherent

skepticism because they're not an impartial actor," said Stephen

Powers, a beverage-industry analyst at UBS.

Meanwhile, negative soda studies and pronouncements are piling

up. In July the Food and Drug Administration proposed that

nutrition labels list added sugar amounts and a recommended maximum

daily sugar intake of 200 calories--40 fewer calories than a

20-ounce Coke. The American Heart Association, a partner in the

Bexar County campaign, recommends that adults limit sugar-sweetened

beverages to 36 ounces a week.

"There is a robust body of evidence linking high intakes of

sugary drinks to obesity," said Rachel Johnson, a heart association

spokeswoman and professor of nutrition at the University of

Vermont. Exercise is important, but a person needs to walk about 1

mile to burn off 100 calories, she added.

San Antonio became a jump ball in this debate in 2010. That year

the city removed sugary drinks from city employee vending machines

as part of a broader health-and-wellness push. That year, the city

also was awarded a $15.6 million federal grant to tackle

obesity.

Two years later, the American Beverage Association, an industry

umbrella group, announced a $5 million grant for a "wellness

competition" between city employees in San Antonio and Chicago. The

partnership "puts the spotlight on ways to do things

collaboratively," Susan Neely, the beverage association president,

said at the time.

Then in 2013, Coke announced $1.5 million in new grants "to get

San Antonians moving" by bankrolling programs that included

distributing bicycles to community centers and military-style

exercise classes called Coca-Cola Troops for Fitness.

A government survey showed progress. It estimated San Antonio's

adult obesity rate dropped to 29% from 35% between 2010 and 2012.

It also found the percentage of residents who drank soda daily fell

to 64% from 71%, suggesting the trends were linked.

Last year, Thomas Schlenker, then director of the San Antonio

Metropolitan Health District, proposed the anti-soda campaign to

drive still-high obesity even lower with a poster of a Rosie the

Riveter look-alike that read: "Soda? No, thank you!"

Several council members opposed the effort, arguing the city

should focus on fitness initiatives instead of telling people what

to eat. "Once you start going down that road, there's an unlimited

number of things you could regulate" including steak, said

councilman Joe Krier in an interview.

Mr. Schlenker said the beverage industry also was given veto

rights over campaign specifics in working committee meetings

attended by a Coke official. Coke said its employee attended as an

industry representative but didn't have veto rights. By January,

the campaign was dead, and in July, Mr. Schlenker was fired.

He believes he was fired because of his tough stance on soft

drinks. In a statement, City Manager Sheryl Sculley said the reason

was "increasing dissatisfaction with his lack of leadership,

continued disregard for direction and repeated instances of

unprofessional conduct." City officials said the beverage industry

didn't exert undue influence on the campaign.

County officials stepped in after hearing the campaign had died

in San Antonio. "It's not a Big Brother thing telling [residents]

you might drink more sugar than you think," said Bexar County Judge

Nelson Wolff, head of the county's governing body.

Their campaign is backed by a coalition of about 20

organizations including the county's public hospital, the San

Antonio Independent School District, South Texas Academy of

Nutrition & Dietetics and American Diabetes Association.

The website www.sugar-packed.com warns of the dangers of sugary

drinks and helps visitors calculate how much sugar they're

consuming when they grab a soda, energy drink, sweet tea or orange

fruit beverage. A video on the website shows a man sitting at a

diner emptying one packet of sugar after another into his mouth

while the woman next to him drinks a cola. "Why would you drink

that much in added sugars?" it asks.

Subscribe to WSJ: http://online.wsj.com?mod=djnwires

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 03, 2015 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

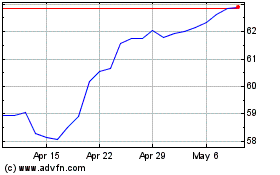

Coca Cola (NYSE:KO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Coca Cola (NYSE:KO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024