After struggling for years to turn around sluggish sales, Sam's

Club is now pursuing a more fundamental fix: breaking away from the

low-income consumers who shop at at its parent, Wal-Mart Stores

Inc.

"We want to be less of a Wal-Mart," said Rosalind Brewer, chief

executive of the warehouse-club retailer that has tried more modest

moves like improving online ordering and adding such services as

tax preparation that appeal to small-business members.

The new strategy means carrying fewer products that appeal to

households that earn $45,000 a year—Wal-Mart's sweet spot—in favor

of targeting wealthier shoppers with more organic food, brand-name

clothes and 1,000-thread count Egyptian cotton sheets, she said

during a recent interview.

Sam's struggle to shake an early focus on mainstream consumers

has become a liability as club stores have evolved into a favorite

among more affluent shoppers who are able to pay a membership fee

for access to discounts on items from large screen TVs to bulk

boxes of peaches. At the same time, big- box retailers and grocery

stores have embraced discounted bulk sizes, without a membership

fee. Rival Costco Wholesale Corp. has thrived, building stores in

wealthy enclaves and delivering strong annual sales gains.

For Sam's part of the challenge is Wal-Mart itself. Wal-Mart

founder Sam Walton created the warehouse chain in 1983 as a place

for small businesses to stock up on discounted bulk items, not as a

Wal-Mart clone that offers everyone everyday deals. But as Wal-Mart

grew, Sam's followed. Now, some 200 of Sam's about 650 U.S. stores

share a parking lot with a Wal-Mart.

"By far, and regardless of region, Wal-Mart is Sam's largest

competitor," says Sara Al-Tukhaim, a director at Kantar Retail, a

consulting and research firm. Kantar data shows that 81% of Sam's

shoppers say they also shopped at Wal-Mart in the past four weeks,

compared with a 15% overlap with Costco, says Ms. Al-Tukhaim.

Twenty percent of Wal-Mart shoppers say they also went to Sam's

Club, she says.

Ms. Brewer doesn't agree that Wal-Mart is her biggest competitor

but she notes that "a winning model is when Wal-Mart operates in

their lane and Sam's in their lane." Most of Sam's products are

already different than Wal-Mart's, but when Sam's sells single

deodorants or Wal-Mart sells five pound bags of frozen

strawberries, the two stores are competing, said Ms. Brewer, who

has been CEO since 2012.

Growth in Sam's club stores open at least a year inched up 0.5%

in its last fiscal year, a gain dwarfed by Costco's 6% increase

over a similar period. For the past five years, Sam's has lagged

behind Costco's growth. Total sales at Sam's hit $58 billion last

year while Costco booked $110 billion from its 664 global stores.

Sam's accounts for about 12% of Wal-Mart's $482 billion in annual

revenue.

Costco has done well in part because it clusters stores around

urban areas and along the country's coasts, drawing a wealthier

clientele that has fared well in the economic recovery. It went

into organic foods early and now offers an average of about 200

organic items per store. Sales of organic food at Costco are about

$4 billion a year, said Richard Galanti, chief financial officer

for Costco, the third largest retailer in the U.S. by revenue.

Mr. Galanti sees Sam's as Costco's most direct competitor, but

he notes that Costco's strength is its laser focus on club stores,

while Sam's is but one of several priorities for Wal-Mart. Costco

also has regional product buyers who can hone purchases to local

preferences. Sam's buyers are all based in Bentonville, Ark.,

Wal-Mart's home.

Sam's has made forays into more premium products like those at

Costco, but frequent leadership changes have stymied efforts to

shake its parent's influence. In 2001, Sam's added expensive

jewelry and said it wanted to sell high-end art to better compete

with Costco. Those plans floundered however when Sam's president

left in 2002. More recently Ms. Brewer's predecessor, Brian

Cornell, added more fresh food and upgraded merchandise. Mr.

Cornell is now CEO of Target Corp.

Running Sam's Club has been a steppingstone to larger jobs at

the parent company. Wal-Mart's current CEO, Doug McMillon, managed

Sam's from 2006 to 2009. Eight executives have run Sam's in the

last 20 years.

Sam's executives are starting to use new technology to study its

consumers, gaining access to data on the specific demographics of

shoppers at each club, including household income by ZIP Code of

shoppers, said Bill Durling, a spokesman for Sam's. That data

showed that 150 Sam's are located in areas with many high-income

shoppers but don't draw enough of those customers.

In two regions, the retailer is testing what a high-end Sam's

might look like, with more individual prepared meals, pricey

furniture, apparel and food alongside rows of bulk Coca-Cola

typical in most Sam's Clubs. The test allows a small team of Sam's

buyers to practice selecting products with wealthy consumers in

mind. The aim is to try to attract shoppers that might also shop at

places like Whole Foods Market Inc.

However, many of Sam's top suppliers don't sell products that

target wealthier shoppers, making the transition more

difficult.

Last fall Sam's buyers called Maple Hill Creamery hoping to sell

its organic yogurt made in New York. "I was absolutely surprised,"

said Tim Joseph, founder of the company.

After the first call Mr. Joseph said he went to his local Sam's

store in Albany, N.Y., and found no organic foods selection. He

rejected Sam's buyers' overtures three times, worried his tart,

full fat, lightly sweetened yogurt wouldn't be a hit with its

customers.

Eventually he was lured to Bentonville, Ark., for a tour of the

flagship store where Sam's buyers explained they are working to add

more premium and organic food, he said. Maple Hill Creamery yogurt

now is being sold in about 150 Sam's Clubs mainly in Michigan,

Texas and the Northeast, but sales haven't met expectations yet,

said Mr. Joseph.

"They are being patient," he said.

Write to Sarah Nassauer at sarah.nassauer@wsj.com

Subscribe to WSJ: http://online.wsj.com?mod=djnwires

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 17, 2015 08:15 ET (12:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

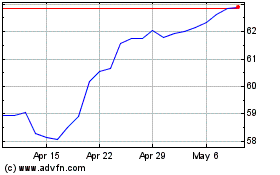

Coca Cola (NYSE:KO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Coca Cola (NYSE:KO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024