By Denise Roland

Jean-Paul and Martine Clozel had to sell their house and work

out of a rented garage when they started biotech company Actelion

Ltd.

Twenty years later, after selling the Swiss company to Johnson

& Johnson in an unusual, $30 billion deal, the husband-and-wife

team is starting over again. They are embarking on the creation of

a new global biotech player -- armed with nearly $1 billion in

capital, a deep-pocketed partner in J&J and soon, a stock

listing in Zurich.

Dr. Clozel, 61 years old, is slated to walk away with about $1.5

billion for his 5% stake in Actelion. Johnson & Johnson

persuaded him to sell only after agreeing to let him strip out

Actelion's early-stage research and development to form a separate

company.

The U.S. health-care giant, eager to replenish its pipeline as

some top-selling drugs face competition from cheaper competitors,

was willing to pay a hefty price tag. That, and its agreement to

the unorthodox deal structure, cleared a hurdle that tripped up

previous Actelion suitors: Dr. Clozel's well-telegraphed reluctance

to give up his independence over years of deal speculation.

"My first reaction to J&J was that I didn't want to sell,"

Dr. Clozel said in an interview. He now will become chief executive

of the new firm, which doesn't yet have a name. Along with his

wife, he will be free to pursue research that spans insomnia, lupus

and neurological diseases.

Johnson & Johnson will hold on to a 16% stake in the new

firm, with an option to double that. The rest will be spun off

later this year to existing Actelion shareholders, giving Dr.

Clozel a 4.2% stake. Johnson & Johnson is expected to provide

more detail on the portfolio in a prospectus for the new company in

coming weeks.

"We know they know how to develop and market drugs," said Daniel

Koller, lead manager at BB Biotech, a longtime investor in

Actelion.

The biotech industry is a key player in the global

pharmaceuticals industry. These research-focused drug-discovery

companies blossomed amid a wave of genetic-engineering advances in

the 1970s and '80s. They tend to stay small and nimble, marketing

only a few drugs they develop, or selling promising drugs to bigger

companies.

But some have grown into pharmaceutical giants in their own

right. Actelion is Europe's biggest by market capitalization, but

it is dwarfed by the likes of Amgen Inc. and Gilead Sciences Inc.

of the U.S.

Johnson & Johnson first approached Actelion in January of

last year. At first, the two companies discussed collaborating, but

J&J then said it wanted to buy Actelion, according to a J&J

filing the following month.

Negotiations stumbled on price. Actelion Chairman Jean-Pierre

Garnier broached the idea of a spinoff. In November, the two sides

disclosed talks.

French company Sanofi SA jumped in the following month, The Wall

Street Journal reported. Sanofi, referred to only as "company A" in

J&J's filing, offered a higher price. J&J wouldn't match

it. Then, Sanofi went back on its offer price, according to the

filing, and Actelion turned back to J&J, which clinched the

deal in January.

Sanofi declined to comment.

Dr. Clozel, a cardiologist, and his wife, Martine, a

pediatrician and also 61, met as medical students in France in

1975. They both joined Roche Holding AG about a decade later and

ended up working on cardiovascular drugs.

Dr. Clozel said he became disillusioned in the mid-1990s, when

he said the company pushed scientists to concentrate on specific

diseases, instead of taking their research in whichever application

seemed most promising.

Jonathan Knowles, Roche's former head of research and

development, said the Clozels' program didn't fit the company's

strategy at the time because it didn't cater to common conditions

such as high blood pressure. A Roche spokesman declined to comment

on the company's past strategy but said that today its scientists

"have a lot of freedom to pursue their own projects."

In 1997, the Clozels quit their jobs at the Swiss drug giant to

set up Actelion in the rented garage in Allschwil, Switzerland,

with two former Roche co-workers. The Clozels sold their house to

contribute funding.

"We had no money; we had no technology, no patents," he said.

The quartet planned to continue the work they had started at Roche,

which had focused on the inner lining of blood vessels, or

endothelium.

The following year, Roche shut down its cardiovascular research

program and agreed to license two of its shelved drugs -- both of

which had been discovered by the Clozels and their team -- to

Actelion. One of those drugs ended up working for patients with a

rare condition known as pulmonary arterial hypertension, or PAH.

Marketed as Tracleer, it pushed Actelion into profitability, and

went on to become a global blockbuster. Actelion listed in

2000.

Dr. Clozel struggled to repeat that success. In 2011, after a

string of clinical-trial failures, Elliott Advisors, an activist

fund, tried to replace management. Dr. Clozel convinced

shareholders to stick with him. The next year, he struck gold

again, notching a big clinical-trial success with its new PAH drug,

Opsumit.

--Jonathan D. Rockoff and Ben Dummett contributed to this

article.

Write to Denise Roland at Denise.Roland@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 02, 2017 07:14 ET (12:14 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

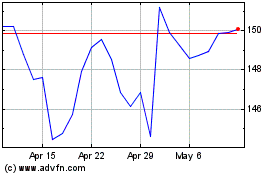

Johnson and Johnson (NYSE:JNJ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

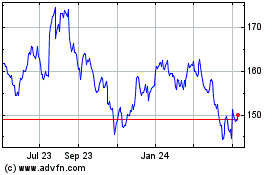

Johnson and Johnson (NYSE:JNJ)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024