(FROM THE WALL STREET JOURNAL 9/2/15)

By Ted Mann

When Honeywell International Inc. was thinking of buying a maker

of hand and foot protection in 2008, one of its executives toured a

Charleston, S.C., factory owned by the target and was shocked.

Bales of raw Malaysian rubber and industrial solvents and dyes

were scattered around the ramshackle plant. The huge vats where

rubber gloves for utility workers were repeatedly dipped until

thick enough to resist 40,000 volts of electricity were badly aged.

The executive called the office and delivered a frank report: This

doesn't look anything like what Honeywell does.

Chief Executive Dave Cote gave the green light to buy the

company, for $1.2 billion, anyway. Honeywell poured in investment,

cutting the lead time for making one of the painstakingly

hand-dipped rubber gloves from a year to 30 days while reducing

waste.

Now Honeywell, best known for building sophisticated products

like 3-D weather radar and aircraft guidance systems, is also in

the business of manufacturing gloves and boots.

Activist investors in companies have made "conglomerate" a dirty

word. Across corporate America, the pressure is on to split up and

concentrate on the most promising lines of business. Yet even as

rival General Electric Co. dismantles its sprawling financial

operations and smaller companies like Danaher Corp. and Johnson

Controls Inc. break up, a select group that includes Honeywell has

bucked the trend toward a sharper focus and drawn cheers from

investors for diversified lineups.

Honeywell has done 84 acquisitions in the 13 years under Mr.

Cote, adding about $12 billion in annual sales and ending up with a

stable of about 65 different brands. The company in late July

announced a $5.1 billion deal for Elster Group, a maker of gas,

water and electricity meters -- the largest acquisition of Mr.

Cote's tenure.

The result is an array of loosely related offerings, from

satellite-based Wi-Fi systems for corporate jets to antistatic

"finger cots," small, rubber finger sheaths used in the assembly of

sensitive electronics and computer chips. The company still makes

the Honeywell thermostats that have dotted the walls of American

homes for generations and which gave the corporation its name. Now,

the same entity boasts "optimal earmuff attenuation" in its hearing

protection gear for industrial workers, while also producing a

range of chemical agents and industrial components for refining oil

and natural gas.

So far, investors approve of the corporate sprawl. The company's

shares Tuesday closed at $95.96, up from $32.65 on the day Mr. Cote

took over in 2002. That 194% gain is more than twice the increase

booked by the S&P 500 over the same period.

The question is whether Honeywell can keep the act going. Small,

disciplined deals for boot makers are no longer enough to make a

meaningful difference in growth at a company with $40 billion in

revenue last year. Investors now want Honeywell to make bigger

deals while keeping risk in check. They worry about the

availability of suitable targets.

Conversely, analysts from Deutsche Bank warned in April that

investors' patience for Honeywell's diverse business lines could

grow short now that peers like GE, under shareholder pressure, are

making dramatic adjustments to their portfolios.

"Companies aren't born with a right to be a conglomerate," said

Steve Winoker, an analyst at Bernstein Research, who briefly worked

for Honeywell as a vice president of global strategy from 2006 to

2007. "That's a right only earned over time. And until you earn it,

the presumption should be you can't do it."

Run well, a conglomerate can make acquired businesses more

valuable by improving management, introducing them to new customers

and expanding overseas. The diversity then reduces the parent

company's exposure to any one risk or market.

But peers have long faced pressure to reduce complexity and

focus on fundamentals. GE, for example, is attempting to sell its

slow-growing appliance business, and is shedding its profitable

financial-services arm.

United Technologies Corp., which has a broad range of businesses

from jet engines to air handlers to food-service equipment,

announced in July it would sell its Sikorsky helicopter unit to

Lockheed Martin Corp. for $9 billion.

Danaher, which has acquired more than 400 companies since 1984,

especially in science and medical technology, announced plans in

May to acquire filtration and fluid management company Pall Inc.

and then split the conglomerate into two separate companies, one

focused on life-science and diagnostics equipment and the other on

measuring instruments and automation.

"Both companies will be able to accelerate revenue and earnings

growth as smaller, more focused, independent businesses," Danaher

Chief Executive Thomas Joyce told investors on a conference call

when the decision was announced.

Johnson Controls, another multi-industry company, recently

announced it would jettison its business making automotive seats

and interiors, to focus on two remaining units that make building

control panels and sensors and battery systems. The company told

investors that the automotive unit would better be able to invest

in new product lines if it was disconnected from the other

businesses.

Honeywell, however, said it remains comfortable with its

breadth. Mr. Cote bristled in an interview that industrial

companies like his are more likely to be questioned about the

diversity of their business lines than firms in other sectors.

Google, for instance, has expanded from Internet searches into

contact lenses, self-driving cars and even robots but seems to get

a pass from investors.

But Honeywell is different from both Google, which recently

announced it would separate its core Internet business from more

experimental ventures, and traditional holding companies such as

Berkshire Hathaway.

Google's new structure is intended in part to prevent its

diverse interests from overwhelming the company's main engine of

profit. While at Berkshire, its various companies operate in

relative autonomy.

Honeywell maintains the structure of a diversified conglomerate,

where three strategic business units rise and fall in their

respective markets, and can help boost one another in hard times.

The three sectors -- aerospace, automation and control systems, and

performance materials -- rely on the headquarters for traditional

functions, like corporate finance and research and development. The

company says it also uses shared distribution and sales networks to

boost sales and generate efficiency across its different product

lines.

Mr. Cote said the real risk isn't in having a diversified

business, but in getting caught up in "fad-surfing" -- trying to

find new markets or business lines that don't fit a company's

strengths or come at too high a cost.

"I've always thought that was a great way to lose a lot of

money," Mr. Cote said.

A decade and a half ago, Honeywell botched a merger with

AlliedSignal, leaving rifts in the management of the company that

hampered cooperation and hurt morale. It left a mess that employees

nicknamed "Honey Hell." The wounded company was then almost taken

over by GE, but when European regulators shot down the acquisition,

it was left with bleak prospects.

Upon arrival at Honeywell, Mr. Cote turned his attention to

integrating factions within the company and cutting waste. He

learned how to do that in the finance department at GE, where he

was a point person on the integration of RCA after CEO Jack Welch

jumped into the broadcasting business in the early 1980s.

As Honeywell's new CEO -- previous CEO Lawrence A. Bossidy had

retired -- Mr. Cote instituted an aggressive but straightforward

acquisition strategy. The company would look for midsize deals in

business lines close to the ones in which it already operated,

ideally in fragmented, tightly regulated, even mundane markets

where Honeywell could instantly become a heavyweight. The

philosophy, Mr. Cote has said, is to have a great position in good

markets.

At the end of the last decade, that logic led to gloves and

boots. The New Jersey-based company expanded from its business

selling fire alarms and security systems into worker safety by

buying a company that had a technology for sniffing out gas

leaks.

From there, Honeywell leapt into personal safety, beginning with

the 2008 deal for Norcross Safety Products LLC, which owned

Salisbury, the dilapidated maker of safety gloves for utility

workers. Norcross's properties also included various lines of heavy

duty rubber boots for firefighters, utility workers and fishermen.

One line popular with fishermen, Xtratuf, once made a high-heeled

pair for Miss Alaska. Another line, Muck Boots, is popular with

hunters and outdoorsmen.

"We own Muck boots?" Mr. Cote said on a postdeal conference call

with his deals team, after learning the brand was one of those

Honeywell planned to dump. He ordered the group to keep Muck and

figure out a way to make it grow, he said.

Fixing Norcross didn't come without headaches. One of the

company's two boot plants in Rock Island, Ill., lacked basic safety

equipment -- a person familiar with the matter called it a

disaster.

Honeywell closed the Illinois facility and spent millions

building a new factory in China, but poor workmanship there caused

the famously watertight boots to leak. Xtratuf devotee Mark Begich,

then a U.S. senator from Alaska, sent Mr. Cote an open letter of

protest about the move to China and the decline in quality. (The

other Rock Island factory, which makes Servus boots, remains in

operation.)

Honeywell blamed the problems on poor worker training, which it

said it amended. It also said it increased inspections and expanded

testing. The aerospace and thermostat conglomerate now commands

rack space in the footwear aisle at sporting-goods retailer

Cabela's -- despite some persistent negative reviews online -- and

has branched out into camp shoes and gardening clogs.

(MORE TO FOLLOW) Dow Jones Newswires

September 01, 2015 19:59 ET (23:59 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

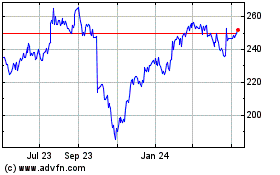

Danaher (NYSE:DHR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Danaher (NYSE:DHR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024