Oil prices fell below $40 a barrel Wednesday amid a growing

glut, putting more pressure on an industry that already is a major

weak spot for global growth.

The immediate cause was a 10th straight weekly rise in U.S.

inventories of crude oil at a time of year when they are expected

to shrink. The market's broader problem, however, is that producers

in OPEC and the U.S. are locked in a battle for market share that

has left the world flooded with oil.

For the past several months, Saudi Arabia has led a policy of

raising oil output to squeeze presumably weaker U.S. rivals in the

U.S. and other countries. But American producers have proved

surprisingly resilient, thanks to deep cost cuts and support from

banks that have kept loans flowing, helping the industry weather

the market's collapse.

The standoff—and discontent with the Saudi policy— is coming to

a head at this week's meeting of the Organization of the Petroleum

Exporting Countries. So far, the kingdom has shown little

willingness to budge.

Late Wednesday, people familiar with the matter said Saudi

Arabia and other Persian Gulf states are willing to cut output as

long as Iran and non-OPEC producers do their part as well.

"We cannot cut alone," one Gulf official said. "Everyone has to

contribute."

Crude-oil futures fell 4.6% to $39.94 in New York on Wednesday,

leaving them down about 25% for the year. Brent, the global

benchmark, fell 4.4% to $42.49 on ICE Futures Europe.

There are signs that cheap oil has benefited industries and

consumers, who are able to spend what they save at the pump. But

the economic calculus has become more complex now that the U.S. has

become a major oil producer in its own right, with the industry a

key source of jobs and orders and with energy stocks and bonds

widely held. The decline in crude has kept inflation subdued,

complicating central bankers' approach to monetary policy.

Oil prices last closed below $40 in the U.S. in late August,

when worries about the global economy roiled financial markets.

Some investors think oil prices will have to spend a long time

around these levels to force producers to give up.

"Prices have to stay low," said Lee Kayser, portfolio manager at

Russell Investments, which manages $237 billion, including $1.6

billion in commodities. "We haven't seen a large-scale flush-out.

We haven't seen many bankruptcies that seem like a sign of the

bottom."

The consequences of the price decline have been severe.

Companies have either deferred or canceled $625 billion of

investments in oil and gas projects that was due to be spent over

the next five years, according to investment bank Tudor, Pickering,

Holt & Co. More than 250,000 people world-wide have lost their

jobs, said Houston consulting firm Graves & Co.

The cuts have helped companies reduce costs and keep pumping

even though prices are now below break-even levels in many

fields.

Meanwhile, supplies are swelling. U.S. commercial inventories of

crude oil and fuel last week soared above 1.3 billion barrels, a

record, according to a report released Wednesday by the U.S. Energy

Information Administration.

Some analysts and investors say the time of reckoning has been

pushed back several months as banks prove reluctant to turn off the

taps.

In their latest review of oil and gas deposits used as

collateral for corporate loans, banks were more lenient than many

investors and analysts anticipated. Lenders shaved an average of

8.6% off the amount companies can borrow so far in the second half

of 2015, according to an analysis by Oil & Gas Financial

Analytics LLC. Industry executives polled by law firm Haynes and

Boone LLP in September expected cuts to average 39%.

As a result, many small and midsize U.S. energy companies have

maintained access to credit lines that allow them to keep pumping

oil and adding to the global supply glut. Banks are inclined to

support producers so the producers can repay their loans in cash

instead of in oil and natural-gas reserves.

Many highly indebted companies have drilled and produced as much

oil and natural gas as possible this year to maximize their cash

flows, keeping total U.S. crude output high and weighing on

prices.

The EIA said Monday that U.S. production averaged 9.3 million

barrels a day in September—down just 2.7% from a 43-year peak in

April.

Although more than three dozen producers have already filed for

bankruptcy protection this year, they have mostly been small

companies that, when taken together, don't produce much crude.

Some investors are eager for banks to take a tougher line.

"From an investor standpoint, it's been, 'Come on already, rip

off the Band-Aid!'" said Janelle Nelson, vice president at RBC

Wealth Management, which manages $280 billion. "I want the pain to

be over with quickly, so that I can piece through all the carnage

and find the good stuff."

The robustness of U.S. output has tested OPEC's yearold policy

of pumping up production to force weaker players out of the market.

During past market downturns, OPEC had cut back its own supplies.

But this time, Saudi officials believed a period of low prices was

needed to squeeze out producers that depended on high oil prices to

survive.

In the U.S., regulators are concerned about banks' energy-sector

loans, and the outcome of this latest semiannual assessment of

energy reserves could prompt more scrutiny. In November, the

Federal Reserve, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency and

Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. said in a report that banks hold a

high number of troublesome loans.

Not all producers got a pass. Oasis Petroleum Inc. and SM Energy

Co., companies that operate in shale-rock regions, each reported

that their borrowing bases were cut by more than 10%. Oasis

declined to comment. SM Energy said its base was cut because it

sold assets.

But the borrowing bases at many firms, such as RSP Permian Inc.,

Northern Oil & Gas Inc. and Bill Barrett Corp., were either

left unchanged or even marked higher in recent months, according to

company disclosures. Callon Petroleum Co., which operates in the

prolific Permian Basin in West Texas, said in October its borrowing

base rose 20% to $300 million.

Callon decided "in January, when we saw the downturn…that we

needed to get as close as we can to our lending banks," said Joseph

Gatto Jr., chief financial officer, according to a transcript of

comments made at an industry conference in November. Among the

company's 10 banks, he said, "everyone is very supportive." Callon

didn't respond to requests for comment.

Producers have slashed spending, but their output is still high

due to improved efficiency, the fact that large-scale projects were

already under way and continued access to equity and debt markets

in the first half of the year.

"If you had asked me this summer, 'Are the banks going to

tighten the screws here in the fall?' Yeah, absolutely," said Will

Nasgovitz, portfolio manager at Heartland Advisors, which oversees

$3 billion. "Now I think it's going to be next spring."

Summer Said

Subscribe to WSJ: http://online.wsj.com?mod=djnwires

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 02, 2015 19:45 ET (00:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

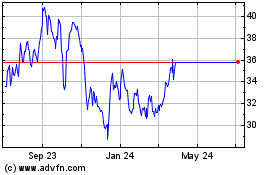

Callon Petroleum (NYSE:CPE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Callon Petroleum (NYSE:CPE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024