By Erin Ailworth

CADDO PARISH, La. -- Doug Lawler watched a drilling rig's

high-pressure pumps rumble as workers bored in to a massive

natural-gas well, part of a new drilling campaign the Chesapeake

Energy Corp. chief executive calls "Prop-a-geddon."

Named for the sand that drillers use to prop open hydraulically

fractured rocks, Prop-a-geddon is an experiment to create supersize

oil and gas wells that the company estimates can extract fossil

fuels for roughly 75% less than typical wells, thanks to

potentially greater economies of scale.

This well, in the Haynesville Shale formation around Shreveport,

La., went 2 miles deep and another 2 miles horizontally, and used

51 million pounds of sand, which the company believes is a world

record. Typical wells in this area extend about 5,000 feet, or less

than a mile.

"It's the biggest job in the history of the Haynesville," Mr.

Lawler said of the massive size of the fracking job under way.

"It's absolutely critical to the company."

In a world where oil prices look poised to stay lower for

longer, even after the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting

Countries agreed to a production cut last week, the challenge for

U.S. shale drillers is no longer unlocking new supplies -- it is

showing they can make money doing it.

For Chesapeake, a deeply indebted pioneer of the U.S. shale boom

co-founded by the late wildcatter Aubrey McClendon, its very

survival may depend on figuring it out.

Under Mr. McClendon, Chesapeake became the second-largest U.S.

natural-gas producer after Exxon Mobil Corp., leading a rush to

lease land for drilling from Pennsylvania to Texas. But in doing

so, it piled up a mountain of debt and a litany of lawsuits that

left it reeling -- and led to the ouster of Mr. McClendon -- even

before energy prices collapsed in 2014.

Mr. Lawler, brought in by activist investors, is selling assets

to pare debt, and trying to transition the money-losing company

into a prudent spender that can produce oil and gas more

economically, and eventually turn a profit.

He estimates the Oklahoma City-based company's true debt was

roughly $21 billion when he took over in 2013. Between 2010 and

2012, the company had spent nearly $30 billion more on drilling and

leasing than it had brought in from operations.

This year, Chesapeake expects to spend no more than $1.75

billion to produce between 617,000 and 637,000 barrels of oil

equivalent a day. That is nearly 90% less than the $14.7 billion

Chesapeake spent in 2012 to produce 648,000 barrels of oil

equivalent a day. Debt, meanwhile, has been cut to $10.9

billion.

Chesapeake has reduced its workforce by roughly 70% to about

3,500 employees and shrunk its drillable land portfolio to about 7

million acres, compared with 15 million at the end of 2012.

Last week, Chesapeake disclosed the sale of 78,000 acres in the

Haynesville to an unnamed private company for $450 million. It

plans to sell an additional 50,000 acres in the field in the coming

months, though it would still retain roughly 250,000 acres.

While the company's turnaround remains far from assured, it has

so far avoided bankruptcy restructuring. That fate, which has

befallen 88 U.S. oil and gas producers since the start of 2015

according to law firm Haynes and Boone LLP, looked possible for

Chesapeake earlier this year, when its stock fell under $2 a share

amid a drop in prices.

Some investors have bought into a comeback: Chesapeake shares

are up fourfold from their 52-week low as asset sales and debt

reductions have diminished concerns. The stock is now trading at

$7.27.

"For what a company has to do now to survive and thrive, they

are doing all the right things," said Robert Clarke, an analyst at

researcher Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

Southeastern Asset Management Inc., headed by Mason Hawkins,

remains Chesapeake's largest shareholder with 10.5% of its stock.

It declined to comment. Billionaire Carl Icahn, who worked with Mr.

Hawkins to recruit Mr. Lawler, sold more than half his stake in the

company in September.

Mr. Lawler would like to cut Chesapeake's debt to $6 billion.

Although the company is still outspending cash from operations, he

expects it to be cash-flow neutral in 2018, assuming an average oil

price of about $60 a barrel.

A big part of hitting those goals depends on what Chesapeake

accomplishes with the vast portfolio of oil and gas fields

originally leased by Mr. McClendon, including some in Wyoming and

Oklahoma in addition to Louisiana.

Frank Patterson, Chesapeake's executive vice president of

exploration and production, told analysts in October that the

company was learning how to get more out of the ground by drilling

and fracking longer wells.

"What we're learning in the Haynesville, we're testing in the

Eagle Ford, we're going to apply to the Utica," he said. "It's a

game changer."

Donning a hard hat and chatting with a work crew, Mr. Lawler was

surveying those lessons firsthand last month in the Haynesville --

and feeling confident a turnaround was under way.

"It's just a matter of time," he said.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 15, 2016 15:50 ET (20:50 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

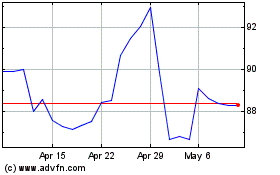

Chesapeake Energy (NASDAQ:CHK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

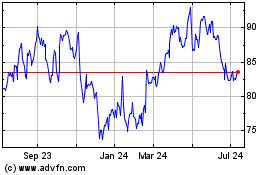

Chesapeake Energy (NASDAQ:CHK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024