By Ryan Dezember and Kevin Helliker

The late oil magnate Aubrey McClendon held his alma mater in

such high regard that he built the headquarters of his company in

the image of Duke University's campus.

And back in Durham, N.C., the feeling was mutual: There's the

McClendon Commons and McClendon Tower, McClendon Plaza and the

Kathleen Upton Byrns McClendon Pipe Organ. All told, Mr. McClendon

gave more than $20 million to the school where he met his wife,

sent his children and connected with the friend who would help

bankroll his rise.

Now, Duke is making a claim against the Chesapeake Energy Corp.

co-founder's estate, claiming it is owed almost half the $18.75

million he recently pledged, even though he died before he could

make good on it.

Mr. McClendon graduated in 1981 and became a major benefactor of

Duke after he struck riches in the oil patch. When he died in March

in a car crash in Oklahoma City, Mr. McClendon had unfunded

commitments to athletics funds, scholarships and campus-improvement

projects totaling about $9.94 million, the university said in a

probate court filing that became public late Tuesday.

Duke is the latest player in a complicated legal drama unfolding

in an Oklahoma City court, where a growing roster of creditors has

come forward with claims against the late wildcatter.

Mr. McClendon borrowed heavily to fund new business ventures and

gave generously to hometown projects and charitable organizations,

but the value of many of his energy-heavy holdings is in question

amid the biggest oil bust in a generation.

The move also raises questions about just how far recipients of

pledges should pursue money promised before a person's death.

Lawyers say the aggressive pursuit of an estate could hurt the

university's ability to persuade alumni to make the kind of firm

commitments its endowment needs to fund obligations into the

future.

In a statement, Duke called Mr. McClendon "one of Duke's most

passionate and generous alumni...This is a routine transaction that

in no way diminishes Duke's respect for the McClendon family and

our gratitude for their relationship to Duke."

Tom Blalock, a longtime associate of Mr. McClendon who is

administering his estate, didn't respond to requests for comment.

Mr. McClendon's creditors, which so far range from Wall Street

banks to a former employee to a farm-equipment maker, have until

Sept. 16 to file claims.

Mr. McClendon left behind a vast tangle of assets and debts when

his speeding Chevy Tahoe crashed into a concrete underpass the

morning of March 2. He had been ousted from Chesapeake over

corporate-governance issues three years earlier and had leveraged

many of his personal holdings to finance a comeback.

Collapsing oil prices in late 2014 strained the new oil-and-gas

empire he had assembled, and he struggled in his final year to

raise more cash to keep it afloat.

Oklahoma records show he had pledged assets as collateral for

loans, including his roughly 20% stake of the Oklahoma City Thunder

basketball team, fine wine, investments in tech startups and

antique boats.

Lawyers for Mr. McClendon's creditors have said they think Mr.

McClendon, who during his Chesapeake heyday was a billionaire, left

behind more debt than assets. The entrepreneur's debts so far

amount to about $500 million, according to Oklahoma probate

records.

But Martin Stringer, a lawyer for Mr. McClendon's estate, said

claiming it is insolvent is "incorrect" because "nobody has the

facts," according to a transcript of a May probate court hearing.

The value of many assets "depends on commodity prices," he added.

He said that the estate includes interests in more than 180

companies and other business ventures.

Duke's claim is the only one yet tied to McClendon's pledged

donations. The university said Mr. McClendon's commitments are in

writing and documented.

"If there's a signed letter of commitment, generally speaking,

that's considered legally binding," said Richard Marker, a

professor of philanthropy at the University of Pennsylvania and New

York University, who added that he doesn't know the specifics of

Mr. McClendon's pledge to Duke.

With documented pledges, Duke should have similar standing to

Mr. McClendon's unsecured creditors, said Laura Zwicker, a partner

at Los Angeles law firm Greenberg Glusker Fields Claman &

Machtinger LLP who specializes in estate matters for wealthy

clients. Government agencies, such as the Internal Revenue Service,

are paid first, followed by secured creditors, who receive the

value of their collateral, she said.

Whatever assets the estate has left are usually doled out

proportionally to unsecured creditors as well as secured creditors

whose claims were not satisfied by collateral, said Ms.

Zwicker.

Duke said that over the years, the McClendons have given more

than $20 million to the school. Mr. McClendon met his wife,

Kathleen McClendon, at Duke, and the couple sent each of their

three children there.

Duke is where Mr. McClendon met his close friend Ralph Eads, an

investment banker who years after their fraternity days helped Mr.

McClendon raise the cash needed to lease huge swaths of

shale-drilling property that made Chesapeake the country's

second-largest natural gas producer. He built Chesapeake's Oklahoma

City headquarters with rows of redbrick Georgian buildings in the

image of the campus.

McClendon Commons is a visitors' center adjacent to Duke's

admissions office. The McClendons gave at least $1.2 million for

the restoration of the massive pipe organ in the university's

chapel.

The university in 2002 tried to memorialize the couple with a

pair of gargoyles carved in their likenesses and installed above an

entrance to McClendon Tower, but the couple insisted they be

removed, according to news reports at the time.

People close to Duke said that news of the appeal caught at

least some members of the university's fundraising office by

surprise.

"How positive is it to see a university sue a donor?" asks Doug

White, former director of the nonprofit management program at

Columbia University. "If it were up to me, I wouldn't push it that

hard."

Duke ran into a problem with a pledge from a different donor a

decade ago. In 2003, Boston Scientific co-founder Peter Nicholas

pledged $72 million to Duke, which at the time made headlines as

the largest contribution in the school's history. The deadline for

payment was December 2008, but it was unfulfilled as of September

2010, according to The Chronicle, Duke's student newspaper. Mr.

Nicholas is still paying off the pledge, according to people

familiar with the matter. Mr. Nicholas, who retired as a director

of Boston Scientific in May, couldn't be reached for comment.

As of 2015 Duke University had the 18th largest endowment among

U.S. schools with $6.5 billion, according to the Council for Aid to

Education, a nonprofit organization that tracks endowments. Duke's

endowment nearly doubled from $3.3 billion over the past decade, an

increase in line with most schools.

--Ben Cohen and Douglas Belkin contributed to this article.

Write to Ryan Dezember at ryan.dezember@wsj.com and Kevin

Helliker at kevin.helliker@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 25, 2016 02:48 ET (06:48 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

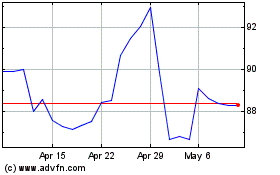

Chesapeake Energy (NASDAQ:CHK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

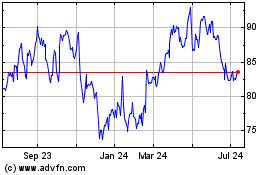

Chesapeake Energy (NASDAQ:CHK)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024