By Anupreeta Das

Ed Prendeville was driving through Omaha, Neb., one winter night

in 1981 when he recalled that Warren Buffett, an investor he had

read about in college, lived in the Midwestern town.

He made a mental note, and two years later the trader of

collectible toy trains had scraped together enough to buy his first

shares of Berkshire Hathaway Inc. for $1,300 apiece. Mr.

Prendeville has been reaping the rewards of that decision ever

since.

"It's my security blanket," the 64-year-old said of the shares,

some of which now trade at over $200,000 each.

In 50 years at the helm of Berkshire, Mr. Buffett has

transformed a struggling textile mill into a massive holding

company with $200 billion in revenue and created a legion of

unlikely millionaires--and even a few billionaires.

One of those shareholders is "Forty-Dollar Frank"--Frank

Fitzpatrick, a Lake Tahoe, Nev., tax lawyer who occasionally

introduces himself that way because he bought his first Berkshire

shares for $40.

Mr. Fitzpatrick recalls buying about 200 shares in early 1976 at

that price, only to sell them 14 months later after they had

doubled. As the stock continued to soar, he regretted the move and

bought back in at an even higher price. Since then, "I've always

had a habit of running back to Berkshire," Mr. Fitzpatrick

said.

In 1995, after he bought his lakefront home in Tahoe, Mr.

Fitzpatrick said his family gathered on the deck "for a group hug

and said, 'Thank you, Warren.'" Although he has used Berkshire

shares to fund an education nonprofit, the 72-year-old says his

remaining Berkshire shares will go to his two children.

Early Berkshire stockholders have used shares to finance

children's educations, buy homes and put up collateral for loans.

Hundreds of millions of dollars of stock already have gone to

shareholders' alma maters, employers, cultural institutions and

medical research.

As those longtime investors age along with Mr. Buffett, who is

85, they too are grappling with how best to pass it on. Mr. Buffett

has pledged to donate almost all of his $62 billion fortune to

charity and has already given away more than $25 billion. In an

interview, he said he expects a "high percentage of big individual

shareholders" will do the same.

The Berkshire chairman holds uncommon sway over shareholders of

his company, and his influence helps explain how many of them view

their wealth.

The billionaire has lived in the same house that he purchased in

1958 for $31,500. He often picks up breakfast for a couple of

dollars at a McDonald's near his office and pays himself a salary

of $100,000. He frequently drives himself around town in his

Cadillac sedan.

Like Mr. Buffett, Berkshire shareholders are an unusual bunch.

Every spring, tens of thousands of them, from money managers and

corporate executives to farmers and rabbis, descend on Omaha for

Berkshire's annual meeting, where their quirks are in full

display.

At an annual dinner organized by a small group of shareholders

on the sidelines of the meeting, the restaurant bill is usually

split multiple ways. Omaha bartenders and waitresses say Berkshire

shareholders are stingy tippers.

Mr. Buffett used to keep track of all his shareholders before

they swelled into the tens of thousands. Beginning in the 1970s, as

Mr. Buffett's renown began to grow, so did Berkshire's shareholder

base.

There are hundreds of Berkshire millionaires in the Portland,

Ore., area alone thanks to a money manager there who had the

foresight to scoop up shares on behalf of clients in the 1970s.

The money manager, Mark Holloway, discovered Mr. Buffett in the

early 1970s after Ben Graham, a legendary value investor who was

Mr. Buffett's mentor, recommended that they meet. Mr. Buffett

didn't have time, but Mr. Holloway said he began buying shares for

himself and for clients of his firm.

Clients paid prices as low as about $400 a share and on average

received fewer than a dozen each. Today, a few hundred are

millionaires in the Portland area, said Mr. Holloway, who manages

about $50 million of his own and clients' money.

Shareholders who want to sell their shares are staring at a huge

tax hit given the stock's enormous rise in value. Charitable

donations, meanwhile, are tax-free and deductible from federal

estate taxes.

"Philanthropy is a smart way out as well as the good way out,"

said Andy Kilpatrick, the author of a 1,286-page book on

Berkshire.

Jim Halperin, a Dallas shareholder who founded a rare-coin

auction company, bought his first Berkshire shares in 1995 when

they were trading around $30,000. His holdings are now worth about

$19 million.

Mr. Halperin, 62, said his views on philanthropy were reaffirmed

by Mr. Buffett's move in 2006 to donate most of his fortune

primarily to a foundation run by Microsoft Corp. co-founder Bill

Gates. Mr. Halperin said he donates about a quarter of his earnings

each year to local causes, and that he and his wife plan to give

most of their millions away.

In March, Omaha residents Bill and Ruth Scott joined the Giving

Pledge, an effort by Messrs. Gates and Buffett to urge the world's

billionaires to give at least half their fortunes to charity during

their lifetimes.

Mr. Scott was the first employee of Mr. Buffett's investment

partnership in the early 1960s and spent his career at Berkshire,

accumulating enough stock to become very wealthy. "Ruth, a farm

girl, likes to compare a 'pile of money' to a 'pile of manure,'"

the Scotts wrote Mr. Buffett. "Neither one does much good unless

you spread it around!"

Mr. Prendeville, who bought Berkshire stock after driving

through Omaha, lives in New Jersey and makes a living buying and

selling collectible trains, said that as profits at his

Parsippany-based business grew, he invested nearly every cent in

Berkshire stock. He put some in accounts for his children and some

in a retirement account for himself. His two sons grew up indulging

their passion for race-car driving, an expensive hobby Mr.

Prendeville might not otherwise have been able to support. His

Hyundai sports a sticker that reads "In Berkshire Hathaway We

Trust."

In 2007, he was diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Without his

Berkshire shares, Mr. Prendeville said it would have been hard to

pay for cutting-edge treatment that his insurer refused to cover.

"I was able to write a check," he said.

Mr. Prendeville--who once found Mr. Buffett a toy train set

modeled after the Midwestern Hiawatha train that the billionaire

coveted as a child--said he is now turning to estate planning. He

has no plans to start a foundation of his own but said he is

struggling to figure it out.

"Where is one dollar of mine going to make the most difference?"

he said. "It's not easy."

Subscribe to WSJ: http://online.wsj.com?mod=djnwires

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 21, 2015 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

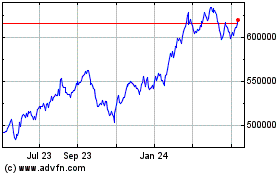

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

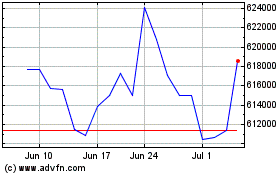

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024