Top executives at Riverstone Holdings LLC, one of the world's

largest energy investment firms, have ceded more than $300 million

of profits they made from investments before the oil bust erased

those gains, according to securities filings and people familiar

with the matter.

The money is related to an incentive formula employed at

private-equity firms in which executives earn a cut of profits

above a certain threshold for each fund.

In Riverstone's case, profits in some of its funds shriveled

after U.S. oil prices plunged to below $27 a barrel earlier this

year from more than $100 in mid-2014. That decline reduced the

value of some companies owned by Riverstone, eliminating paper

gains and requiring some executives to return profits in a

so-called clawback.

David Leuschen and Pierre Lapeyre Jr., who founded Riverstone

and remain its majority owners, are the primary recipients of its

portion of deal profits, known as carried interest. Through a

spokesman, Messrs. Leuschen and Lapeyre declined to comment.

While most private-equity funds usually keep details of their

fund performance and structure private, industry executives say

clawbacks are rare. Most firms want to avoid having to recall

payments made to executives, some of whom may have left the firm or

already spent the cash.

What's more, diversified private-equity firms make investments

across a number of sectors that balance a fund's results; losses on

one deal can be offset by profits on another.

But funds that focus on oil and gas, which exploded in

popularity since the start of the shale boom, have become

particularly vulnerable to big swings in performance because their

profits are highly susceptible to changes in energy prices.

David Fann, chief executive of TorreyCove Capital Partners LLC,

which vets private funds for investors, said clawbacks in energy

funds are becoming more common as low oil prices continue to pummel

investments made when prices were much higher. "It's the new normal

for investors in oil funds," he said. "They're realizing the

challenges of oil volatility."

A clawback is a feature of private-equity funds intended to

assure investors they will earn a minimum return, often 8%, before

the fund managers take their share of the profits—and that fund

investors won't be left holding the bag if investments lose value

after fund managers cash out of early successful deals.

The mechanics vary from firm to firm, but many pay out deal

profits as they are earned and don't repay them until the end of a

fund's life, which is often 10 years or more.

It's unclear how much, if any, cash Riverstone executives

personally have had to surrender back to the fund. They could hold

off until the fund is liquidated, hoping that oil prices bounce

back and their debts are erased. The firm typically holds a portion

of its deal profits in escrow to avoid having to ask executives to

repay large sums should investments lose value, according to a

person familiar with the matter.

Riverstone isn't alone in having profits slip away in the oil

bust. Private investment funds focused on oil and gas lost roughly

22% of their value in 2015, a crushing year that has negated

several prior years of gains, according to investment adviser

Cambridge Associates LLC. For the five years ended Dec. 31, such

funds have an annualized loss of 0.06%, after fees, Cambridge

says.

Riverstone was founded in 2000 by the two former Goldman Sachs

Group Inc. energy bankers as the shale boom was taking off. One of

the New York investment firm's early funds, launched in 2002,

produced annualized profits of about 55% after fees, according to

public pension records.

Money poured into subsequent funds from pensions and other

institutional investors eager to get in on the shale boom and

renewable energy, one of Riverstone's other specialties. Riverstone

became a landing spot for former Goldman bankers as well as former

oil company CEOs from firms like Anadarko Petroleum Corp. and BP

PLC. Even as crashing oil prices rippled through its holdings,

Riverstone has continued to raise billions of dollars for new

funds. Riverstone has raised $34.2 billion, since its inception,

including some $7 billion since oil prices crashed.

The firm initially partnered with Carlyle Group LP, which helped

the upstart raise money and handle back-office functions in

exchange for a stake in Riverstone's funds. That partnership lasted

for several funds before Riverstone struck out on its own for a

$7.7-billion fund it raised in 2013.

Carlyle said in a securities filing that as of June 30 it had

set aside $76 million in gains it owes back to three funds it

manages alongside Riverstone based on the investment pools' present

value.

Each of the three Riverstone funds that Carlyle says are subject

to the clawback remained profitable for investors as of June 30 but

have fallen below the minimum level of profitability that entitles

the firms to a cut of the gains. They are the only of Carlyle's 34

funds in clawback, company filings show.

When Carlyle reported second-quarter results last week, analysts

asked executives why another of its funds, which had gained enough

for the firm and its shareholders to start taking their cut, hadn't

started paying out. Carlyle's executives said they wanted to ensure

the profits were permanent lest they wind up having to return

money.

"Investors aren't happy with clawback," said Carlyle co-CEO

David Rubenstein, "but the professionals in our firm are even less

happy when we have to claw back."

Dawn Lim contributed to this article.

Write to Ryan Dezember at ryan.dezember@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 02, 2016 14:45 ET (18:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

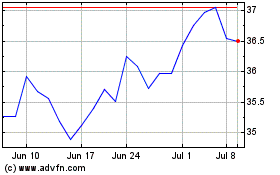

BP (NYSE:BP)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

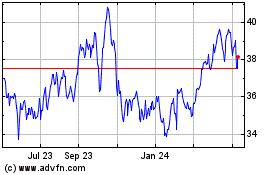

BP (NYSE:BP)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024