Regulators to Call for Banks to Have Year's Worth of Liquidity

April 25 2016 - 7:30PM

Dow Jones News

WASHINGTON—Large U.S. banks would have to prove they have enough

cash to withstand severe market turmoil lasting as long as a year

under a new rule set to be proposed Tuesday.

The regulation would require about 30 of the country's biggest

banks to adjust their balance sheets, cutting the odds they would

run into the kind of funding crunch that crippled Bear Stearns and

Lehman Brothers in 2008. But critics say it could also crimp banks'

profits by forcing them to devote more resources to low-return

investments or higher-cost sources of cash, and could disrupt

markets by forcing banks to curb their trading in certain types of

instruments or pull back from certain types of loans.

The rule is being crafted by three agencies: the Federal

Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. and the Office of the

Comptroller of the Currency. The FDIC will release details of the

liquidity proposal at its board meeting Tuesday, along with voting

on an unrelated postcrisis rule to rein in incentive-compensation

on Wall Street. That bonus-pay proposal is being prepared by six

regulators and was released last week by one of them, the National

Credit Union Administration.

The core element of the new regulation is the "net stable

funding ratio," or NSFR. This new requirement would force banks to

show they have sufficient "stable funding" to help them endure a

year of extreme duress. The idea is to encourage banks to rely more

on sources such as core deposits and longer-term funding from small

businesses, and less on short-term wholesale funding—which includes

instruments such as repurchase agreements—that help to provide

another way for large banks to get cash.

The question banks are waiting to see answered is whether the

U.S. version of the NSFR will be similar to one suggested by global

regulators two years ago or whether U.S. officials will follow

their pattern of "gold-plating" international rules by imposing

stricter requirements. Banks also fear that regulators won't just

give them numerical benchmarks to meet, but issue detailed rules

prescribing for them what kinds of transactions are needed to meet

those benchmarks.

Critics of the coming rule say they worry that while it might

make banks safer, it could undermine the smooth functioning of

different parts of the financial system by forcing banks to pull

back from sectors where they have traditionally played a major

role—essentially shifting potential liquidity problems from banks

to the broader financial system.

In addition to worries within the industry, "there is

significant fear among even global regulators that maybe this is a

problematic result in terms of undermining market liquidity," said

Karen Shaw Petrou, a managing partner of advisory firm Federal

Financial Analytics Inc.

Some industry observers also warn about a "chilling effect" on

long-term lending such as aircraft, shipping and project finance,

according to a memo by the law firm Shearman & Sterling

assessing the possible impact of the new rule. The regulation would

effectively raise banks' costs of keeping such longer-term assets

on their books to offset more expensive longer-term liabilities,

according to the memo.

The one-year stable-funding requirement was completed in 2014 by

the Basel Committee, and is one of the remaining pieces for U.S.

regulators to complete their version of that global framework.

These regulations are designed to make banks less likely to face

distress to avert a potential collapse. The Basel proposals aren't

binding, but come in the form of recommendations for regulators to

carry out in their own economies.

Many of the rules are aimed at forcing banks to maintain more

capital on their books to ensure they have a buffer to protect

against losses from risks they take. Those have existed for years,

though they have been strengthened since the crisis.

A new layer of postcrisis protections is aimed at ensuring banks

have sufficient liquidity to protect against a sudden funding

crunch, a modern version of a bank run, even if their underlying

balance sheets are healthy. As the financial crisis began to unfold

in 2007, "Many banks—despite meeting the existing capital

requirements—experienced difficulties because they did not manage

their liquidity," according to a document from the Basel Committee

on Banking Supervision, the group of global regulators proposing

the NSFR rule, explaining the rationale behind it.

The first such regulation in place, completed by three main

American bank regulators in September 2014, is called the

"liquidity coverage ratio." That requirement calls on large banks

to hold highly liquid assets such as central bank reserves, and

government and corporate debt, which can be converted into cash

quickly to cover a firm's obligations over a 30-day period.

The new regulation to be proposed Tuesday is aimed at addressing

stresses that could emerge in a bank's balance sheet if a financial

crisis lasts longer than a month.

The NSFR regulation will apply to roughly 30 U.S. banks with $50

billion or more in total consolidated assets on their balance

sheets, excluding client money. But, if past practice is any

indication, U.S. policy makers will likely impose a more-stringent

rule on the eight largest and most complex banks that hold $250

billion or more in assets, including J.P. Morgan Chase & Co.

and Bank of America Corp., while applying a more relaxed standard

to banks that have more than $50 billion in assets but aren't

internationally active.

A spokesman for J.P. Morgan couldn't immediately be reached,

while a spokesman for Bank of America declined to comment.

"This process should result in a regulation that reduces the

probability of banks coming under short-term funding pressures,"

Fed governor Daniel Tarullo said in 2014 speech previewing the

liquidity rules. "Maintaining more stable funding, such as retail

deposits and term funding with maturities of greater than six

months, will help avoid the spiral of fire sales of illiquid assets

that deplete capital and exacerbate market stress."

Write to Donna Borak at donna.borak@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 25, 2016 19:15 ET (23:15 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

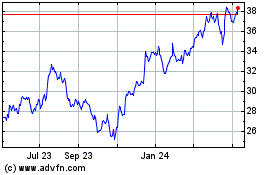

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

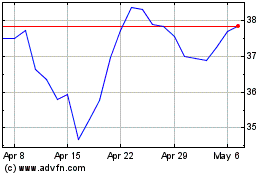

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024