By Michael Rapoport And Ryan Tracy

Faced with new global regulations requiring them to strengthen

their capital, big lenders in the U.S. and Europe have turned to a

trading tactic that flatters their positions without actually

raising extra funds.

Banks that have done such "capital-relief trades" include some

of the largest in the world: Citigroup Inc., Bank of America Corp.,

Deutsche Bank AG and Standard Chartered PLC. But the Office of

Financial Research, a U.S. Treasury office created to identify

financial-market risks, is suggesting the trades run the risk of

"obscuring" whether a bank has adequate capital and pose other

"financial stability concerns."

The Securities and Exchange Commission and the Federal Reserve

also have also voiced concerns about the trades.

Capital-relief trades are opaque, little-disclosed transactions

that make a bank look stronger by reducing its "risk-weighted"

assets. That boosts key ratios that measure the bank's capital as a

percentage of those assets, even as capital itself stays at the

same level.

In a capital-relief trade, a bank can keep a risky asset on the

balance sheet, using credit derivatives or securitizations to

transfer some of the risk to a hedge fund or other investor. The

investor potentially gets extra yield and the credit risk of

smaller borrowers in a way it would be hard for them to get

otherwise, while the bank gets to remove part of the asset's value

from its closely watched "risk-weighted asset" count.

Banks say the trades help them manage their risk, even if they

don't go as far as a bona fide asset sale, and are just one tool

among many they are using to meet new capital requirements.

Some say the Office of Financial Research is mischaracterizing

the transactions, or that the trades didn't significantly affect

their capital ratios. Bank of America, for example, disclosed $11.6

billion in purchased capital protection in 2014 regulatory filings,

but said the impact of the trades on its capital ratios was less

than 0.01 percentage point.

Critics fear the trades can spread risk to unregulated parts of

the financial system--just as similar trades did before the

financial crisis.

"It just seems like another repackaging of risk to mask who's

holding the bag," said Arthur Wilmarth, a George Washington

University law professor and banking expert.

The trades are allowed under banking regulations and securities

laws, but recently have drawn attention in part because banks don't

say a lot about them. The financial-research office said in a June

report on the trades that banks should be required to disclose more

about them.

Banks have made significant progress in increasing capital

ratios to meet the new global requirements. This year, all 31 U.S.

banks the Fed surveyed under its annual stress tests stayed above

its minimum capital requirements for the first time, and the Fed

said the banks' core capital would have been 8.2% of risk-weighted

assets even under deep-recession-like conditions, up from 5.5% in

2009.

But they have more to do: The required capital levels for banks

will rise dramatically by 2019 as governments implement new

regulations known as Basel III. The Fed said in July it will

require still more capital at the biggest U.S. banks.

While some banks have reduced their risk-weighted assets this

year, 30 global banks that regulators label "systemically

important" reported that total risk-adjusted assets increased about

11% between 2012 and 2014, according to data provider Bureau van

Dijk.

The financial-research office said in the June report that 18

U.S. banks had disclosed in 2014 regulatory filings that they used

$38 billion in credit derivatives for "purchased protection" for

regulatory-capital purposes, up from 13 banks in 2009.

The Office of Financial Research didn't identify the banks, but

a review of regulatory filings by The Wall Street Journal indicates

that they include Citigroup, Bank of America, Goldman Sachs Group

Inc. and Morgan Stanley.

Some of the 18 U.S. banks say the trades weren't driven by a

desire to improve their capital ratios. "We don't enter into any

transactions for the sole purpose of artificially reducing

risk-weighted assets or increasing regulatory ratios," said a

spokesman for Citigroup, which had $16 billion in purchased capital

protection in the fourth quarter of 2014. He didn't specify the

impact of the trades on Citigroup's capital ratios.

Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley declined to comment.

Standard Chartered PLC has done 12 capital-relief trades since

2005. In one, a March 2014 trade that was part of a series dubbed

"Start," the bank transferred some of its risk on a pool of EUR1.5

billion ($1.67 billion) in loans to small and medium-size

companies. Deutsche Bank unloaded some of its risk on EUR2.35

billion in loans earlier this year with another variant of a

capital-relief trade, known as synthetic securitizations.

A spokesman for the Office of Financial Research said it is

possible the trades have only a "minimal effect" on capital ratios,

but the study showed the banks don't disclose enough information to

draw that conclusion.

The Fed in 2011 said capital-relief trades "can significantly

reduce a banking organization's level of risk" and has said in

recent years it scrutinizes the trades based on pricing, rationale

for the transaction, and other factors. Fed officials declined to

discuss specific transactions.

The SEC's concern is that some capital-relief trades might not

really get risk off a bank's balance sheet, said Michael Osnato,

chief of the complex financial instruments unit in the SEC's

enforcement division.

Wayne Abernathy, an American Bankers Association executive vice

president, says it is important to recognize the distinction

between "keeping the loan on your books without any cover, and

sharing the risk with somebody else."

Firms that advise on or invest in the deals include

Christofferson Robb & Co. and Ovid Capital Advisors LLC. "We

were attracted to transactions that transferred well-underwritten

loan risk," said Glenn Blasius, Ovid's CEO.

One worry about such trades is that they shift risk to funds and

other investors that aren't as closely regulated as banks. Before

the financial crisis, European banks bought $290 billion worth of

credit default protection from American International Group Inc.

for regulatory capital relief, the Office of Financial Research

noted. That protection likely would have proven worthless had it

not been for the bailout AIG received later.

Today's transactions are complex enough that regulators may miss

some of the risks, adds Thomas Hoenig, vice chairman of the Federal

Deposit Insurance Corp., who favors stricter and simpler capital

rules. "It's a little bit catch-as-catch-can," he said.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 17, 2015 19:22 ET (23:22 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

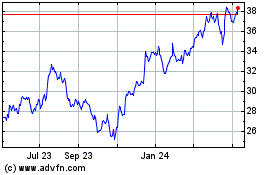

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

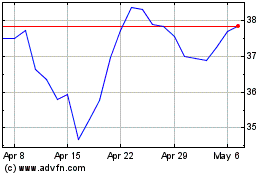

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024