By Jon Ostrower

Boeing Co. is on pace to achieve a rare feat in its industry:

delivering a new jetliner ahead of schedule.

The 737 Max, an updated version of its best-selling single-aisle

jet, completed its first flight Friday, a key step toward Boeing's

goal of delivering the first plane to Southwest Airlines Co. in the

third quarter of 2017.

Behind the scenes, industry officials say, Boeing is telling

customers it might deliver the jet as much as six months early.

Just being on time would be remarkable. Aerospace companies in

recent years have struggled with on-time deliveries of products,

including commercial jetliners, business jets, military transports

and fighter aircraft, because of technical and production

problems.

Boeing hasn't been immune. Its flagship 787 Dreamliner and the

updated 747-8 version of its iconic jumbo jet were years behind

schedule and suffered billions of dollars in cost overruns.

The 737 Max is the fourth big change in the 50-year history of

the 737, the best-selling jetliner of all time. Boeing received its

first orders for the model in late 2011 at a time of high fuel

prices. The plane boasts new engines and improved aerodynamics that

the company said could cut fuel consumption by at least 14%

compared with prior models.

Boeing needs a smooth transition to the Max from the existing

plane to ensure its cash-cow status continues uninterrupted.

Analysts estimate the 737 accounts for between 40% and 45% of the

operating profit of the company's commercial-airplane business.

"The 737 has been the meat and potatoes for the company," said

Herb Kelleher, a founder and former chief executive of Southwest.

"I think it has been a sustaining element for Boeing for a

considerable period of time, something they could always count upon

in bad times as well as good."

Southwest only flies 737s and has ordered 974 of them, including

200 Max versions.

Rival Airbus Group SE has eroded Boeing's traditional dominance

of the single-aisle market, and it had a jump on upgrading its own

offering. Airbus began signing up customers for a new version of

its competing A320 with more fuel-efficient engines a year before

Boeing started selling the 737 Max.

Airbus on Jan. 20 delivered to Deutsche Lufthansa AG the first

of those A320neo jets, which through 2015 had garnered 4,471

orders, compared with 3,072 for the new Boeing jet.

Progress on the 737 Max could still hit obstacles. Flight

testing, for example, could reveal unexpected problems. Still, the

737 Max is an update, rather than an all-new model like the 787,

requiring fewer tests. Boeing also is planning conservatively,

allowing six years from program launch to delivery, compared with

just four years it originally allotted for the 787--which ended up

being nearly eight years after delays. Boeing's test pilots said

they plan nine months of aerial tests for the Max, but have given

themselves 20 months--the same as the 787, despite that plane's

bigger technological leap.

"I don't want to cut [the allotted testing time] to the bone and

have to add days on to the end, and unfortunately we have done that

in the past, " said Keith Leverkuhn, Boeing's program manager for

the 737 Max.

While big upgrades like the Max are tied to advances in engine

technology, Boeing has incrementally improved the 737's design over

many years. The result is a deep pool of Boeing engineers who know

the plane well, making more-extensive upgrades easier, say current

and former Boeing executives.

The 737 Max adopts some of the Dreamliner's advances, such as

consolidating traditionally analog cockpit indicators onto

laptop-sized widescreen displays. But it retains some of the 737's

1960s attributes, such as its switch-laden overhead panel and

analog indicators, which helps airlines keep their pilots trained

and certified for the new jet--critical for their cost

calculations.

While the list price of a 737 has steadily increased--currently

$110 million for the most popular model of the Max, the cost to

airlines after discounts has come down. A new 737 Max sells for

about $51 million, including average discounts, compared with an

inflation-adjusted $58 million for a new 737-400 in 1990, estimates

Avitas, an aircraft valuation and consulting firm. The same has

been true for Airbus jets.

The downward pressure on prices is reflected in airplane

factories that have been transformed over the past two decades.

Boeing's Renton, Wash., plant builds 42 737s a month, twice the

rate of 10 years ago and all under the same roof. By 2019, the

number is expected to be 57.

Boeing hopes to build the 737 Max for at least 15 years, and

Chief Executive Dennis Muilenburg last week said Boeing remains

confident in its strategy of updating its best seller rather than

pushing an all-new plane. But customers and company staff say

Boeing officials privately have expressed concern and are devising

ways to more quickly recoup market-share losses, particularly for

the biggest single-aisle aircraft. Airbus currently has nearly four

times as many orders as Boeing in that market segment.

Customers are pushing for an all-new jet, bigger than the Max

but smaller than the Dreamliner. Boeing also is studying a

less-expensive option that would be ready sooner. The design

features new wings and stretches the 737's body to seat up to 245

passengers and adds taller landing gear to make room for larger

engines, said people familiar with the studies.

Mr. Leverkuhn defended the largest 737 Max, which Boeing aims to

deliver in 2018, and said the cost to fly a trip in the biggest 737

is lower than its Airbus counterpart and its design is exceeding

its original performance. "We're comfortable with where the

airplane is landing," he said.

Write to Jon Ostrower at jon.ostrower@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 02, 2016 05:44 ET (10:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

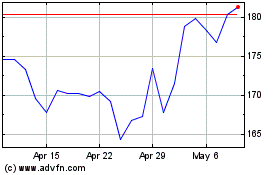

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Boeing (NYSE:BA)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024