By Tom Fairless

BRUSSELS--This city of bureaucrats has become a place of

pilgrimage for West Coast technology firms.

From Amazon.com Inc. to Uber Technologies Inc., the giants of

Silicon Valley are bulking up in the European Union's de facto

capital, hiring lobbyists and jostling for the favor of the Web's

most ambitious regulators.

Smaller U.S. firms are showing up, too, drawn by a muscular

antitrust agency that has meted out billions of dollars in fines to

tech giants such as Intel Corp. and Microsoft Corp.

Google Inc., which is under particular pressure in Brussels,

more than doubled its outlays on lobbying of EU institutions last

year from 2013, according to figures disclosed publicly in an EU

database.

EU regulators this spring accused Google of skewing results to

favor its comparison-shopping service, and demanded it change how

its search engine functions. The company is also facing a second EU

antitrust inquiry over its control of the Android mobile-operating

system, which powers roughly three-quarters of the world's

smartphones.

The battles being fought out in Brussels could determine the

future shape of the Internet and help decide competitive struggles

among companies based halfway across the world.

"Brussels is the most important place in the world from a tech

policy standpoint," said Luther Lowe, head of public policy at

business-review website Yelp Inc. in San Francisco, which has filed

a separate complaint with EU authorities over Google's search

practices. Mr. Lowe said he has spent seven months of the past two

years in Belgium's capital, and recently appointed a full-time

lobbyist here.

Casey Oppenheim, a San Francisco-based Internet entrepreneur,

planned his family vacation this year around a trip to Brussels.

Mr. Oppenheim filed a complaint here in June alleging that Google

had unfairly pulled a privacy application created by his firm,

Disconnect Inc., from its Play mobile app store last year. Google

said the app, which aims to stop other apps from collecting data on

users, violated a policy prohibiting software that interferes with

other apps. Disconnect is available on Apple Inc.'s iOS App Store,

Mr. Oppenheim said.

At a time when Europe often struggles to project power beyond

its own borders--and even within them--its muscular Internet policy

stands out.

In the past four months alone, the EU became the first regulator

in the world to file antitrust charges against Google; it opened

several major inquiries into possible abuses by U.S. search engines

and price-comparison websites; and it pushed ahead with antitrust

probes into companies including Amazon and Qualcomm Inc. The tax

affairs of Apple and Amazon are under scrutiny in Brussels, and EU

policy makers are putting the finishing touches to a tough new

data-privacy regime that they hope to establish as a global

standard.

Faced with that onslaught of scrutiny, U.S. firms are staffing

up.

Google, Microsoft and IBM Corp. are among the top 10 companies

in Brussels by the number of high-level meetings with the EU's

executive branch since December, according to data compiled by

Transparency International, an anticorruption organization. That

puts them ahead of giant European firms like BP PLC and Deutsche

Telekom AG.

Google last week sent its formal response to the EU's antitrust

charges regarding its comparison-shopping service. The company

argued that regulators had erred in their analysis of the

fast-changing online-shopping business, misconstrued Google's

impact on rival shopping-comparison services and failed to provide

sufficient legal justification for its demands.

The EU will now consider Google's response before making a final

decision, which could take another 18 months or more. It could fine

Google up to 10% of its global annual revenue if it judges the

company to have violated EU law, and impose immediate injunctions

on its business practices. Google could then challenge the ruling

in European courts, a process that could last many years.

In the U.S., regulators closed their own investigation into

Google's search practices two years ago after the company agreed to

voluntary changes.

The EU's decision to file charges against Google has encouraged

entrepreneurs like Mr. Oppenheim to seek redress in Brussels. His

lawyer, Gary Reback, who is based in Menlo Park, Calif., said he

frequently advises clients to fly nine time zones rather than catch

a taxi to the U.S. Federal Trade Commission's offices in San

Francisco.

John Lapham, general counsel at Seattle-based Getty Images, said

he has visited Brussels twice this year. Getty, the world's largest

photo agency, complained to EU antitrust officials earlier this

year that Google had unfairly favored its own image-search service

over rivals.

"A lot of U.S. companies are pleading their case in Brussels

because we have big customer bases in the EU...and Brussels is the

only spot on the planet right now that has the willpower to stand

up to Google," Mr. Lapham said.

For an institution that lacks the ability to raise and spend

taxes, antitrust policy has long been the sharpest weapon in

Brussels's armory. It has been used aggressively since the 1950s to

smash down national barriers to a single European market for goods

and services.

A history of battling national governments and entrenched

interests has left the EU with few qualms about taking on the most

powerful companies.

By contrast, U.S. antitrust cops stepped back from some tough

enforcement measures over the past decade, lawyers say. A turning

point, they say, was a decision by the U.S. Department of Justice

in Sept. 2001 to drop an aggressive plan to break up Microsoft.

Meanwhile, the EU has slapped the Redmond, Wash. software giant

with some EUR2.2 billion ($2.5 billion) in fines.

Unlike U.S. regulators, the EU doesn't need to prove antitrust

cases before a court--because it is itself the judge--and the

bloc's appeals courts in Luxembourg have rarely overturned its

decisions. Brussels is also under a greater obligation to consider

all complaints made against companies like Google, or explain why

it has rejected them, EU and U.S. officials say.

China's competition authority is seen as a future powerhouse

that could eventually rival Brussels and Washington--and something

of a wild card given its broad focus on industrial policy goals.

But antitrust enforcement is still in its infancy in China, and

U.S. Internet firms are less present given the country's focus on

building homegrown rivals to firms like Google and Amazon.

Crucially, concerns around the use of personal data by large

Internet firms are much more prevalent in Europe, particularly in

mighty Germany. Those concerns have intensified since Edward

Snowden's revelations of widespread surveillance of European

citizens by U.S. security services.

Yet the EU's assertiveness in an online world that is dominated

by U.S. names is fraught with risks. Besides concerns about

protectionism raised by President Barack Obama and others, Internet

firms worry that Brussels might end up as final arbiter for the

global Internet.

"It's unusual to have Europe serving as a proxy for U.S.

companies," said Tim Wu, a former adviser to the FTC who is known

for coining the phrase "net neutrality," the principle that

Internet service providers should enable access to all content

equally.

Back in San Francisco, Mr. Oppenheim says he feels a lot better

for his trip to Europe. "People are very receptive," he said.

"There's a general understanding that the Internet is a global

entity. If the EU regulates...it doesn't just impact the EU."

Write to Tom Fairless at tom.fairless@wsj.com

Subscribe to WSJ: http://online.wsj.com?mod=djnwires

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

September 02, 2015 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

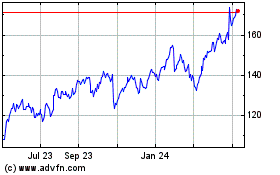

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

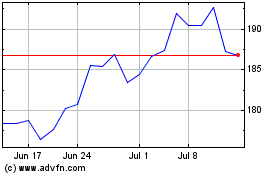

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024