(Editor's Note: This item originally appeared earlier today. It

is being sent to run on additional wires.)

By Annie Gasparro

Food makers are racing to find acceptable alternatives to sugar.

But it's hard to replace a taste that so many Americans have grown

to love.

Traditional sweeteners -- from sucrose, or table sugar, to

high-fructose corn syrup -- are an increasing concern to consumers

and lawmakers, who see them as a key culprit in America's obesity

and diabetes epidemic.

Now researchers at food giants, startups and universities are

looking for new ways to make foods sweet without putting people's

health at risk. Some are testing out natural zero-calorie

ingredients like monkfruit and South American root extracts that

are so intensely sweet that they can add flavor without calories.

Others are manipulating granules of sugar to make them taste

sweeter. They're also developing new ingredients that will block

bitter taste receptors and make food seem like it has more sugar

than it does.

Nestlé SA scientist Olivier Roger, who's leading the food

titan's sugar-reduction effort globally, says many companies are

working on finding answers. Adding to the urgency: Some companies,

like Nestlé, have self-imposed deadlines for lowering sugar content

in food.

But there are big challenges to removing what has been a key

ingredient in processed food for over a century.

For one thing, there are side effects to removing sugar: It not

only adds sweetness but also functions as a preservative and adds

texture, as well as contributing to the overall volume of food.

Whole recipes have to be rethought when it is removed. And after

finding an alternative, companies may face higher costs, supply

constraints or regulatory hurdles related to the substitute

ingredients.

"It's very difficult, very complex. We still don't have the

magic solution that would replace sugar," Mr. Roger says.

The push comes amid a widespread effort to put the brakes on

sugar consumption. In a survey released by market-research firm

Nielsen earlier this year, 22% of respondents said they already

restrict their sugar intake. Most major food makers, including Mars

Inc., General Mills Inc. and Kellogg Co., have pledged to reduce

sugar in candy, children's cereals and other products.

Last year, the federal government called out sugar consumption

as a problem in the U.S. Dietary Guidelines, recommending for the

first time that people consume no more than 10% of their daily

calories from added, or refined, sugars. Americans currently

average 13% of their calories from added sugar, the report

says.

Regulators also said last year that food and beverage makers

will be required to disclose on nutrition labels how much sugar has

been added to products, as a distinct item within the total sugar

content. The FDA recently extended the deadline for the new labels

to Jan. 1, 2020 from July 2018.

Cutting the amount of sugar will be a steep task. More than

22,000 products in the U.S. contain high-fructose corn syrup,

according to food labels cataloged by Nielsen and Label Insight, a

provider of food-label data. Even foods widely seen as healthy

contain added sugars. For instance, among yogurt products, 86%

contain added sugars of some kind, as do 79% of shelf-stable juices

and drinks.

Years ago, when consumers were trying to cut calories in

general, artificial sweeteners such as aspartame (Equal) and later

sucralose (Splenda) gained popularity, and scientists thought they

had cracked the code. Now those products have come under scrutiny

by consumer advocates over health concerns. While there is still a

debate among the scientific community, the Center for Science in

the Public Interest, CSPI, warns that artificial sweeteners may

post a slight risk of cancer. More than half of Americans surveyed

by Nielsen said they avoid those artificial sweeteners.

One avenue researchers are exploring is altering sugar itself.

Nestlé, which adds sugar to chocolate bars, ice cream and

less-obvious products like frozen dinners, says it has discovered a

way to make sugar particles dissolve faster when people eat them.

That allows people to taste the sugar immediately so that the

product seems sweeter, allowing the company to reduce sugar content

by up to 40%.

Hershey, meanwhile, says it has patented technologies that boost

sweetness by altering the surface area and shape of sugar particles

in chocolate. It wouldn't provide details of how shape impacts

taste, but some scientists say that when there's more surface area

to touch the tongue's taste receptors, a food can seem as sweet

with less sugar.

DouxMatok, an Israel-based food-tech company, says it has

patented technology that intensifies the sweetness of sugar by

attaching sugar molecules to what it calls a carrier that targets

certain taste buds and makes the sweetness linger. That can reduce

the sugar content in food by up to 40%, depending on the product,

the company says.

More than sweetness

Even if scientists find a way to reduce sugar, that isn't the

end of the problem. For one thing, if you take out sugar, you end

up with a product that isn't, well, as big as it used to be.

The high-tech sugar Hershey has developed allows the company to

use less, but it needs to add something to make up the volume, or

its chocolate bars would shrink. Replacing sugar with more of the

other ingredients -- such as milk or cocoa butter -- can add fat,

and that's viewed as a negative.

If you take out 30 grams of sugar, you have to put in 30 grams

of something else, and it also has to be healthy, says DouxMatok

Chief Technology Officer Alejandro Marabi. "Every category has

different challenges. Chefs and food scientists every day will have

recipes they try and test," he says.

Sugar also serves a lot of functions in food beyond making it

sweet, and they aren't easy to replicate. "What many people may not

realize is that sugar plays several roles in chocolate," like

affecting the texture, a Hershey spokesman says.

For instance, Nestlé's Mr. Roger says, "if you remove sugar from

ice cream, you have an ice cream that is very, very hard."

Adding fiber, however, can soften it. "You have to have a

combination of different ingredients to overcome different gaps

that we have when we reduce sugar," he says.

Sugar also acts as a preservative because it binds with water,

not allowing bacteria to grow. Removing it from bread can enable

mold to grow faster.

Some researchers now say natural, high-intensity sweeteners that

come without calories are the future of sweetness. But current

alternatives such as stevia and monkfruit can have a bitter

aftertaste.

Researchers around the world are testing ingredients derived

from mushrooms that block bitterness. They can be added to coffee

drinks and dark chocolate to reduce the amount of sugar. Or they

can offset the unwanted aftertaste of those natural zero-calorie

sweeteners.

But even when they find the right combination of ingredients, it

can be difficult to source them. One all-natural sweetener that has

recently become a popular candidate for tests is a syrup from

yacon, a South American root that is relatively hard to find in the

U.S. Even if it works great, it's currently too expensive, one

food-company scientist says.

Some companies are finding solutions closer to home. Ahold

Delhaize NV, a European grocer with nearly 2,000 stores in the

U.S., says it removed 500,000 pounds of sugar from its own brands

in 2015 and 2016. For its juices, food scientists found sweeter

varieties of apples and other fruits, says Jacqueline Ross,

director of product development for Ahold USA. "It's important to

take out [added sugar], but also to not replace it with something

else that may not be liked, like artificial sweeteners, " she

says.

Allison Fickett, a dietitian and regulatory manager at Daymon

Worldwide, a grocery consultancy, says some of the company's

clients are reducing added sugar in products that contain fruit by

picking it when it's riper and cooking it a bit longer to enhance

caramelization. That method "doesn't require reformulating or

investing in new food technology," she says.

Eve Crampon, senior product developer at Stonyfield yogurt, says

she and her team have worked for more than two years to reduce the

sugar in its yogurt. They screened the thousands of strains of

bacteria cultures until they found the right combination that

produced a less tart yogurt and thus required less added sugar.

"Finding the right strain that would be mild without posing other

challenges took a while. We had to test a lot of strains," she

says.

---

Ms. Gasparro is a staff reporter in The Wall Street Journal's

Chicago bureau. Email annie.gasparro@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

October 16, 2017 13:53 ET (17:53 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

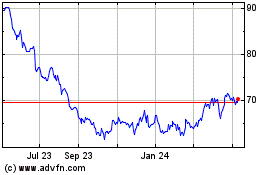

General Mills (NYSE:GIS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

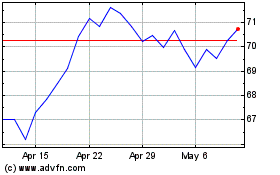

General Mills (NYSE:GIS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024