Should You Follow Berkshire Hathaway Into Apple Stock?

May 20 2016 - 9:38AM

Dow Jones News

By James Mackintosh

Douglas Adams had a wonderful way to navigate in the days before

GPS: the author's hapless detective Dirk Gently would simply find a

car which looked like it knew where it was going, and follow it.

Most investors are lost most of the time, and a surprising number

follow the Douglas Adams strategy: imitate someone who seems

smarter.

The sheer amount of money behind such copy-and-paste strategies

was on show this week when Berkshire Hathaway revealed it had

bought $1 billion worth of Apple shares in the first quarter.

Berkshire chairman Warren Buffett is widely regarded as one of the

smartest investors of all time, and his acolytes--and plenty of

others--follow his holdings obsessively.

Not just obsessively: fanatically. The news added $18 billion to

Apple's market value on Monday. Apple's market capitalization

increased as much as the next five biggest gainers in the S&P

500 combined.

Copying Mr. Buffett makes some sense, assuming it was indeed Mr.

Buffett who made the investment, not one of his two deputies

charged with running big investment portfolios. He is a (very)

long-term investor with a good eye for quality companies that tend

to do well over time.

Mr. Buffett may be more famous than most, but the portfolios of

the leading hedge funds, disclosed in regulatory filings known as

13-Fs, attract significant attention, too. A mini industry has

grown up online allowing investors to track what the hedge-fund

stars are doing, and imitate their financial heroes. Investment

banks are also in on the game: several have created indexes of the

shares the big hedge funds prefer.

But academic evidence shows investors should be cautious about

simply trying to mimic what hedge funds are up to. For starters,

the information is imperfect. The 13-Fs show only U.S. shares the

funds have bought, or taken options on. They ignore short bets,

foreign stocks, bonds and futures. They are delayed by up to 45

days (Monday was the deadline), giving agile hedge funds plenty of

time to change their mind and dump a stock. And about a third of

their holdings are missing entirely, as they ask the SEC for

permission to keep them secret.

The past year's pummeling of crowded hedge-fund trades suggests

that at times it pays to do the exact opposite what the supposed

"smart money" is up to.

Start with the good news: Shares do indeed go up after big-name

managers disclose positions. But the effects wear off quickly, or

are small. Research this week from S&P Global Market

Intelligence shows that buying stocks in which the biggest hedge

funds had increased their holdings most, and selling those they cut

back the most, would have slightly beaten the market. But the

effort involved for a 0.22% average outperformance of the market

over the following month, before trading costs and tax, really

isn't worth it.

Academics have previously found a more significant two-day

effect, but that is for fast-moving day traders, not investors.

Over a month, a study a few years ago by Stephen Brown of New

York's Stern School of Business and Christopher Schwarz of the

University of California found no impact from 1999 to 2008.

Tweaks can improve the figures. Taking just the "best ideas" of

the biggest hedge funds--the stocks they hold the most of--returned

an extra 0.49% over a month, according to S&P. Nice to have,

but hardly a way to Buffett-style riches, given there are only four

chances a year to try this out.

The bad news is that these small gains are interspersed with

giant losses. Hedge funds rushed for the exit this year as their

biggest holdings began to fall, and their selling made them fall

even further. A Goldman Sachs equal-weighted index of the most

popular 50 stocks held by hedgies plummeted 16% in the first six

weeks, while an equal-weighted version of the S&P 500, also

calculated with dividends reinvested, lost only 11%. Since the

index was created in November 2007, the S&P has provided a

better return than the top hedge-fund picks.

More embarrassing still for the smartest guys in the room is

that the stocks they were betting against -- or Goldman's proxy for

them--rose far more than the hedge funds' favorites, and slightly

beat the market.

It is easy to bash the stock-picking skills of hedge funds

(Valeant, anyone?). Much worse is the tendency of hedgies to crowd

into the same stocks, pushing up prices and making them all look

like geniuses, until they all head for the door at the same

time.

The 13-F filings can be very useful for spotting the moments

when hedge funds are all copying each other. That is the time to

worry that any upset might see a violent exit crush the crowded

trades. At other times the best ideas of the smartest managers, at

least those who don't trade too frequently, make a good starting

point for investors. But be warned: there's no substitute for doing

your own analysis.

Write to James Mackintosh at James.Mackintosh@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 20, 2016 09:23 ET (13:23 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

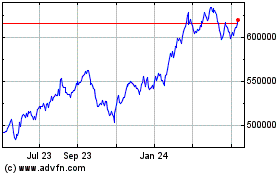

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

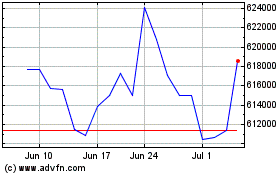

Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024