Race Tightens for Next Wave of Cancer Drugs

March 06 2017 - 9:47AM

Dow Jones News

By Peter Loftus

WILMINGTON, Del. -- In the race to develop the next wave of

drugs that use the immune system to fight cancer, scientists scurry

up and down escalators in an old department store here.

Their biotechnology company, Incyte Corp., set up shop in a

former John Wanamaker store on the outskirts of Wilmington in 2014.

Escalators that once ushered shoppers to home furnishings now take

researchers to labs that are among the most closely watched in drug

development, as Incyte attempts to develop a new generation of

cancer immunotherapies.

Existing immunotherapies including Merck & Co.'s Keytruda

and Bristol-Myers Squibb Co.'s Opdivo have transformed cancer

treatment, boosting average survival rates in lung and skin

cancers.

But the current immunotherapies don't benefit all patients -- a

limitation spurring the industry to hunt for new ways to push

immune cells to destroy tumors. Companies big and small are racing

to develop these new medicines, which analysts say could help boost

global cancer immunotherapy sales to more than $40 billion a year

by the middle of the next decade, from more than $6 billion in

2016. The field is so hot, activist investors including Carl Icahn

recently bought shares in Bristol-Myers out of interest in the

company's immunotherapies and other drugs.

Researchers are now studying more than 1,100 immunotherapy

drugs, up from about 500 two years ago, according to the Cancer

Research Institute, a nonprofit that funds immunotherapy

research.

Analysts say Incyte is one of the closest to market with the new

immunotherapies. Credit Suisse estimates Incyte's experimental

drug, epacadostat, could generate global sales of at least $3.4

billion in 2025 if regulators approve it for sale, an expectation

that has helped more than double Incyte's market value to over $25

billion in the past year. Incyte, which already sells a separate

drug called Jakafi for blood cancers, reported global revenue of

$1.1 billion last year.

"We are at the beginning of an entire field where we can see

applications in every type of cancer," Herve Hoppenot, a former

head of Novartis AG's oncology unit who became Incyte's CEO in

2014, said in an interview.

Analysts caution that the promising data in early studies of

epacadostat may not translate into positive results in the larger

trials now under way. And Incyte faces intense competition from

other companies developing new immunotherapies.

Incyte scientists discovered epacadostat based partly on

fetal-development research at the Medical College of Georgia in the

1990s. That research showed that the immune systems of pregnant

women don't reject fetuses because the placenta harbors an enzyme

called IDO1. Subsequent research at Université Catholique de

Louvain in Belgium found that tumor cells exploit the same enzyme

to prevent the immune system from destroying them.

Epacadostat, taken as a pill, is designed to block IDO1 on and

around tumor cells to allow the immune system to shrink tumors.

Incyte's research on the IDO1 program began in 2005, at a time

when few people thought immunotherapy could effectively fight

cancer. Peggy Scherle, Incyte's vice president of preclinical

pharmacology, recalls showing a slide presentation that year to the

company's top executives listing the pros and cons of targeting

IDO1. One con she included in her slides: "Immunotherapy has never

been shown to work."

The company screened tens of thousands of chemical compounds,

finding one that seemed to block the effects of IDO1, Ms. Scherle

said.

Early studies showed that when used as a stand-alone drug it had

a limited effect. But the drug showed promise in subsequent studies

when used in combination with Merck's Keytruda, which works on the

immune system in a different way. A closely watched study of that

combination in melanoma patients is due to be completed in

2018.

Incyte also is testing epacadostat in combination with other

immunotherapy drugs developed by Bristol-Myers, AstraZeneca PLC and

Roche Holding AG. Incyte got a boost in January when it agreed with

Merck to test the epacadostat-Keytruda combination in several

additional tumor types beyond melanoma, including lung cancer.

Incyte started as a California biotech focused on DNA sequencing

in the 1990s but shifted to drug discovery after hiring a new CEO,

Paul Friedman, who previously led the pharmaceutical unit of

chemical giant DuPont Co. He moved Incyte to Delaware and hired a

batch of former DuPont scientists after DuPont sold its

pharmaceutical unit; Dr. Friedman retired as CEO in 2014.

Incyte initially rented lab space from DuPont, but as it grew

executives wanted a home of their own. The old Wanamaker store,

known to area shoppers for having a stuffed teddy bear on a swing,

had closed in the early 1990s and was later converted to office

space.

Incyte Chief Scientific Officer Reid Huber says the old store's

high ceilings turned out to be ideal for labs because there was

plenty of room to run pipes above drop ceilings. Incyte has

received economic incentives from the Delaware state government to

remain in state, and is currently constructing a second building on

the site.

Write to Peter Loftus at peter.loftus@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

March 06, 2017 09:32 ET (14:32 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

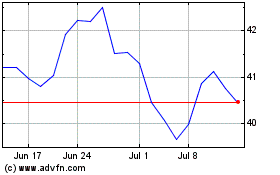

Bristol Myers Squibb (NYSE:BMY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

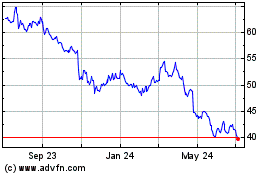

Bristol Myers Squibb (NYSE:BMY)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024