The possible merger between DuPont Co. and Dow Chemical Co.

would create a chemical-industry colossus spanning industrial

materials and agriculture, prompting what would likely be a

detailed and lengthy review by government antitrust enforcers.

Combining the two U.S. industrial icons, which would create a

company with a market value of more than $130 billion based on

Wednesday's share prices, would likely draw complaints from some

farmers and other customers wary of market concentration.

Adding to the uncertainty, the merger talks come as U.S.

enforcers have blocked several high-profile deals.

Still, a deal could well meet regulatory muster, some analysts

said, because Dow and DuPont don't directly compete in many of

their biggest products and could divest assets in areas where they

do overlap, like corn seeds and housewrap.

"For the last 10 years, the companies have not truly been

competitors," said Jonas Oxgaard, an analyst with Sanford C.

Bernstein. Dow and DuPont "used to be the two big rivals in

American chemicals, but they've gone down completely divergent

paths."

Dow, based in Midland, Mich., and DuPont, based in Wilmington,

Del., are discussing a merger of equals that would lead to a

three-way split of the combined businesses into new companies

centered on agriculture, plastics and other chemical-based

materials, and specialty products like enzymes, The Wall Street

Journal reported Tuesday.

According to people familiar with the talks, the parties have

spent little time on antitrust because their lawyers believe there

is little concern thanks to the pending three-way split, which is

intended to ease pushback. The companies plan to bill the combined

company as only a temporary vehicle to cut costs before splitting,

and believe there is minimal antitrust overlap across those

businesses.

Seth Bloom, a Washington-based antitrust lawyer not involved in

the talks, said that combining two large firms isn't necessarily

bad from an antitrust perspective. But he also said it won't

necessarily help Dow and DuPont that they want to break a combined

firm into three new businesses. "What will matter is what kind of

position those businesses have in the marketplace," he said.

Dave Andrea, senior vice president and chief economist for the

Original Equipment Suppliers Association, an automotive suppliers

group, said any combination between major suppliers would prompt

customers to evaluate sourcing.

Wendel Lutz, who farms about 500 acres near Dewey, Ill., said he

worries that further consolidation among farm suppliers could lead

to higher prices at a time when farmers are struggling with three

years of diminished crop prices. "Whenever you have a lack of

competition, it's not going to be a good deal for the purchasers of

those products," he said.

The talks are taking place as both companies have grappled with

collapsing commodity prices that have pressured key customers, and

a strengthening U.S. dollar that has made Dow and DuPont's products

more expensive overseas. The companies are targeting about $3

billion in cost cuts, according to people familiar with the

discussions.

In plastics, both Dow and DuPont develop ethylene-based

products, but target different portions of the market, according to

William Young, managing director at ChemSpeak LLC, a chemical- and

agricultural-industry consultancy. To vehicle makers, Dow sells

adhesives while DuPont sells under-the-hood components, analysts

said. By combining the two, "you get a more full-service supplier,"

Mr. Young said.

Adding DuPont's relatively modest U.S. ethylene-processing

capacity to Dow's would raise the combined entity's annual capacity

to 10.3 billion pounds a year from Dow's current 9 billion, and

represent about 15% of the national total, Mr. Young said.

Sealed Air Corp., which produces plastic wrap and plastic

packaging for the food industry, is a large-volume buyer of resins

from Dow, but has scaled back its business with DuPont. A spokesman

for the North Carolina-based company said a merger "probably

wouldn't have a huge impact on us. DuPont's interest in this

business has been waning, but there are a lot of intermediate

[companies] that can give you supply."

In the third sector, specialty chemicals, Dow and DuPont sell

different products to some of the same customers. For solar panels,

Dow sells modular plates, and DuPont sells pastes that help

transmit power. DuPont sells enzymes to food makers, while Dow

produces polymers for hair gels and lotions.

The Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission, which

review mergers, both have brought notable legal challenges to deals

this year. They also have approved other closely scrutinized

mergers.

Mr. Bloom, the antitrust lawyer, said he would expect a

Dow-DuPont deal to get close scrutiny. "This is not the easiest

time to get a deal through," he said. Regulators are "going to do a

very granular review."

Sometimes the antitrust agencies consider more than just

traditional head-to-head competition between two companies that are

seeking to merge.

For example, some antitrust observers had questioned whether the

Justice Department had much of a basis to object to Comcast Corp.'s

proposed bid for Time Warner Cable Inc., given that the two

companies didn't compete head-to-head in the same geographic

markets.

Despite the lack of geographic overlaps, the department focused

on concerns the deal could cause competitive harm by giving the

merged firm too much power over broadband, TV channel owners and

the future development of the online video marketplace.

Comcast dropped the deal earlier this year in the face of

objections from the Justice Department and the Federal

Communications Commission.

David Benoit, Alison Sider and Bob Tita contributed to this

article.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 09, 2015 20:25 ET (01:25 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

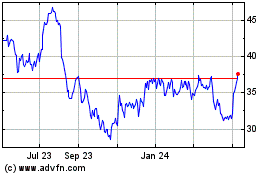

Sealed Air (NYSE:SEE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

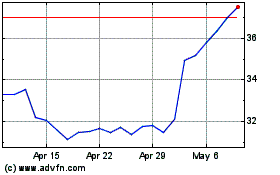

Sealed Air (NYSE:SEE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024