BRUSSELS—For Google, it's a tale of two continents.

On one side of the Atlantic, European competition authorities

unveiled on Wednesday a second set of charges against the Alphabet

Inc. subsidiary, this time over its Android operating system. On

the other side, Canada dropped its probe against the company this

week, following U.S. regulators who have so far found that Google's

conduct raises no antitrust concerns.

Why the difference? Many Americans assume it is largely

explained by a protectionist European response to the dominance of

U.S. technology companies.

European Union officials vehemently deny any such effort.

Experts in competition law say the trans-Atlantic divide is

explained by a host of other factors, including contrasting legal

processes, distinct views on the free market and different

benchmarks for what constitutes anticompetitive behavior.

True, Google and the other U.S. tech giants don't have the

political sway in Brussels that European officials believe they

have in Washington, where they have provided an important growth

story since the 2008 financial crisis.

But a bigger contrast lies in the greater power that resides in

the competition authority in Europe and in the person of the

competition commissioner, Danish politician Margrethe Vestager, who

took over in November 2014.

Since Ms. Vestager took over, her department has targeted

America's biggest tech companies, including Amazon.com Inc. and

Qualcomm Inc., with a slew of antitrust probes. Some major U.S.

corporations are among companies that have found their tax deals

with European governments under scrutiny using her department's

powers to investigate illegal state aid.

Google has been her highest-profile target. She announced

charges last year related to Google's comparison shopping service,

a case started by her predecessor. But the Android case was

launched under her watch and carries her personal signature.

In its various investigations into Google's conduct, the

commission has clashed with Google over the tech giant's alleged

maneuvers to exploit its powerful position to prioritize the

company's own services and impede rival efforts. In Android and

through the company's shopping service, it views Google as hurting

consumers by limiting their options.

But in response to the commission's charges against Android,

Google general counsel Kent Walker rejected the claims, saying the

mobile operating system was "good for competition and good for

consumers."

In her speeches on her approach to the role, Ms. Vestager has

emphasized fairness, suggesting she is looking out for the underdog

who may find it hard to enter markets dominated by behemoths.

In an interview with The Wall Street Journal earlier this month,

she said that the law should ensure small players have "a fair

fighting chance."

"Even though some [companies] are big, they are not above the

law," she said.

In the U.S., antitrust regulators have a high bar, needing to

prove a criminal case in a court that can mete out jail sentences

as well as fines. Class-action lawsuits can multiply the financial

damage to those found guilty, also increasing the deterrent to

anticompetitive behavior.

In the EU, the process is administrative. Nobody will go to jail

and the worst outcome will be fines, of up to 10% of company

revenues, and demands to change conduct.

An appeal is possible to the EU's top court, but lawyers say the

court tends to look for legal and procedural errors rather than to

create precedent for future competition cases.

David Anderson, Brussels-based partner at Berwin Leighton

Paisner LLP, says some in the U.S. are uncomfortable with a process

in which they see the commission acting as "prosecutor, judge and

jury" in relation to antitrust investigations, decisions and

fines.

Nicolas Petit, a professor of competition law at the University

of Liè ge, said the U.S. approach is more free-market driven than

the European. EU case law on the abuse of market dominance is

significantly stricter than in the U.S.

He said the EU focuses more on protecting small companies from

being put out of business by bigger rivals. "They're more worried

about the big size of some companies," he said. "Big is bad."

A remote risk of anticompetitive consequences is enough to find

liability in Europe, whereas U.S. officials must satisfy a higher

burden of proof, he said.

"If you're a dominant company operating in Europe, there's a

presumption against you that any aggressive behavior, like

aggressive pricing for example, is abusive," he said.

Write to Natalia Drozdiak at natalia.drozdiak@wsj.com and

Stephen Fidler at stephen.fidler@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 20, 2016 20:45 ET (00:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

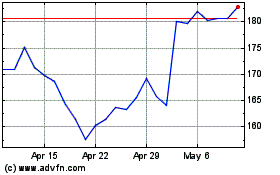

QUALCOMM (NASDAQ:QCOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

QUALCOMM (NASDAQ:QCOM)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024