By Wayne Ma

HONG KONG--Hong Kong businessman Daniel Cheng was meeting

clients in southern China on Aug. 11 when an urgent message from

his finance manager appeared on his phone: The Chinese yuan had

dropped 2% against the dollar.

Mr. Cheng was stunned. For the past three years, his revenues

soared from selling wastewater treatment equipment to

coal-gasification plants in China. His bottom line was boosted by a

steadily strengthening Chinese currency that made the parts he

purchased in euros from overseas suppliers such as Germany's

Siemens AG and France's Schneider Electric SE cheaper to

import.

Now he needed a rethink. Having just banked a payment of around

10 million yuan, he had to decide what to do with it. He advised

his manager to sit tight in case the yuan bounced back.

By the time Mr. Cheng was back in Hong Kong a day later, the

yuan had slipped further. Alarmed that it appeared the Chinese

government was deliberately allowing the depreciation, Mr. Cheng

bit the bullet and ordered his yuan stash be converted to Hong Kong

dollars, a currency pegged to the U.S. dollar. He took a 3% hit in

the process.

China's surprise decision to allow its currency to more closely

reflect market valuations caught everyone doing business in or with

the world's second-largest economy off guard. The delayed reaction

by Mr. Cheng was typical of business owners because each had to

make complex calculations depending on factors such as where they

make and sell their products, and in what currencies they do

deals.

Even a small move in currencies can be the difference between

profit and loss for companies working in China's hypercompetitive

industries, where factory product prices have declined for more

than three years.

In Mr. Cheng's case, the move hurt him two ways. Besides losing

out converting revenue made in China--his biggest market--it also

increased the cost of the imported components he bought in euros.

Even so, he said his operating margins meant he could absorb the

loss and remain profitable.

While the yuan has stabilized at about 2.8% down on the dollar

from Aug. 10, the central bank's decision has raised fears among

business owners that China's economy may be slowing more than

thought. Investors are further spooked by plummeting Chinese stock

prices that have wiped 38% off Shanghai's benchmark index since

mid-June.

Jolted by the currency move, Mr. Cheng, managing director at

Hong Kong-based Dunwell Group, is now seeking to readjust his

operations.

Mr. Cheng has contacted foreign suppliers to ask that they quote

prices in yuan. "We have to pay in whatever currency they ask for.

They won't lock in the price for us," Mr. Cheng said at his office,

located next to one of the firm's manufacturing plants in a Hong

Kong industrial park. "We're not a giant company...we don't have

that kind of leveraging power."

Mr. Cheng also started scouring for replacement suppliers within

China.

Mr. Cheng's exposure to the yuan has increased over the past

three years as China replaced Hong Kong as his main market. He has

hived off as much as 70% of manufacturing to China and sources more

parts there to reduce currency risk, but he continues high-end

assembly in Hong Kong and still needs foreign parts.

Sourcing products from within China is an effective way to

reduce risk. Willy Lin, the managing director of a half-century-old

family firm making sweaters in China, moved all its manufacturing

to China from Hong Kong around the turn of the century. That was

just as the yuan ended its peg and began a long march of

appreciation against the dollar, increasing costs of imported raw

materials including cashmere yarn. Now he sources 90% of his raw

materials in China. Mr. Lin stands to gain from overseas sales if

the yuan's value remains lower or slips further, because he is paid

by overseas customers in foreign currency.

Mr. Lin's trading savvy comes from hard-earned lessons over the

past three decades. He weathered a massive Chinese devaluation of

the yuan in 1994, when it dropped by a third after China first

unified exchange rates for domestic and foreign companies. And, in

the 1997 Asian financial crisis, he dealt with jumping labor costs

in China as its then dollar-pegged yuan soared relative to Asian

neighbors such as Thailand, where currencies were depreciating.

Mr. Lin, like many Hong Kong businessmen whose fortunes are

closely intertwined with China, protects himself against volatility

by buying currency in advance at fixed rates through forward

contracts.

Such tactics are common among those most heavily exposed to

foreign currency swings, such as Stanley Lau, who manufactures

watches for high-end brands. His firm imports components from

Europe to assemble at his factory in southern China and then sells

the finished products back overseas, with most of his deals done in

Swiss francs.

When the Swiss franc depreciated after he booked an order, he

earned less than he thought on the deal. As a result, he hedges

about half his risk.

"We pay a little bit of premium for the insurance," he says.

That premium is going up. Before the Aug. 10 devaluation, a

company would have paid a 2% premium to hedge its exposure to the

Chinese yuan for six months. Since then, the premium has more than

doubled to 4.67%.

Mr. Cheng, the wastewater treatment entrepreneur, said he

doesn't think the cost of hedging is worth it for the size of deals

he makes.

His company's wastewater systems are custom-designed, he said,

so sometimes there are so many parts bought in different currencies

that fixing the cost of one of them wouldn't make sense.

With profit margins ranging between 15% and 20%, Mr. Cheng's

firm has a cushion that other manufacturers, such as textiles

makers, don't have, he said. Besides, he said, the currency move

was relatively small.

"It's not the end of the world," he said. "The important thing

is to try to get the next job."

Anjani Trivedi contributed to this article.

Write to Wayne Ma at wayne.ma@wsj.com

Subscribe to WSJ: http://online.wsj.com?mod=djnwires

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 24, 2015 13:45 ET (17:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2015 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

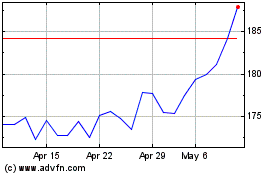

Siemens (TG:SIE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Siemens (TG:SIE)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024