As central banks run out of bonds to buy, they flood

corporations with cheap money

By Christopher Whittall

The European Central Bank's corporate-bond-buying program has

stirred so much action in credit markets that some investment banks

and companies are creating new debt especially for the central bank

to buy.

In two instances, the ECB has bought bonds directly from

European companies through so-called private placements, in which

debt is sold to a tight circle of buyers without the formality of a

wider auction.

It is a startling example of how banks and companies are quickly

adapting to the extremes of monetary policy in what is an already

unconventional age. In the past decade, wide-scale purchases of

government bonds -- a bid to lower the cost of borrowing in the

economy and persuade investors to take more risk -- have become

commonplace. Central banks more recently have moved to negative

interest rates, flipping on their head the ancient customs of money

lending. Now, they are all but inviting private actors to concoct

specific things for them to buy so they can continue pumping money

into the financial system.

The ECB doesn't directly instruct companies to create specific

bonds. But it makes plain that it is an eager purchaser, and it

lays out the specifics of its wish list. And the ECB isn't alone:

The Bank of Japan said late last year it would buy exchange-traded

funds comprising shares of companies that spend a growing amount on

"physical and human capital, " essentially steering fund managers

to make such ETFs available to buy.

The furious central-bank buying has been a relief to companies

and governments that can now borrow at rock-bottom interest rates.

But it has also spurred criticism that the extreme policies are

killing the returns available to other investors, such as pension

funds, and loading up the economy and financial system with

potentially overpriced debt.

The ECB was late to the central-bank party -- it began

quantitative easing only in 2015, years after the U.S., the U.K.

and Japan -- but it has embraced bond-buying with fervor. In March,

it boosted its purchases to EUR80 billion ($90.6 billion) a month

from EUR60 billion and surprised investors by saying it would soon

add corporate bonds to its shopping list.

It had already bought so many government bonds that it was

running out of things to purchase.

The ECB had bought more than EUR16 billion of corporate bonds as

of Aug. 12, according to the latest available data from the central

bank, after starting purchases in early June. The lion's share has

been already-issued bonds trading in secondary markets, but some

has come in new debt sales, according to the ECB.

And Morgan Stanley has arranged two private placements that have

been bought by the ECB, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis

of data from Dealogic and national central banks.

The ECB cited its website when asked to comment on the

corporate-bond-buying program. On Thursday, it updated information

on the site to clarify that the bank can participate in private

placements. The ECB isn't involved in defining the characteristics

of the bonds in these sales, a spokeswoman for the central bank

said.

Private placements are private debt sales not open to the

broader market, typically relying on a handful of investors that

want to buy a company's bonds.

For the company, such a sale allows it to raise cash quickly

without having to draft a bond prospectus. Investors, for their

part, are guaranteed to get a sizable chunk of the bonds they want

to buy without having to compete with the wider investment

community.

"Typically there won't be a prospectus, there won't be any

transparency, there won't be a press release. It's all done

discreetly," said Apostolos Gkoutzinis, head of European capital

markets at law firm Shearman & Sterling LLP.

The ECB executes bond purchases through the eurozone's national

central banks, which function like branches.

The Bank of Spain holds some of a EUR500 million private

placement issued by Spanish oil company Repsol SA on July 1, and

some of a EUR200 million deal from Spanish power utility Iberdrola

SA sold on June 10, two days after the ECB program got under

way.

Both deals were solely arranged by Morgan Stanley and are the

only private placements issued since the start of the ECB's

corporate buying program to have been bought by national central

banks, according to the Journal analysis. Morgan Stanley declined

to comment.

Iberdrola didn't respond to requests for comment. A spokesman

for Repsol said it makes sense for the company to lock in low

borrowing costs in bond markets. "It's all about bringing your

global interest payments as low as possible," the spokesman

said.

It is impossible to say exactly how much the ECB holds, because

the national central banks that make the purchases disclose only

which bonds they have bought, not the amounts. For almost the first

six weeks of the program they didn't give any details about which

bonds they had bought.

Still, the scant data are enough to make traders and strategists

scramble to divine what the big fish is buying. Guessing right can

pay off. Yields on corporate bonds have plunged in Europe. (Yields

fall when prices rise.) The average yield on euro investment-grade

corporate bonds is 0.65%, according to Barclays, compared with

0.99% before the program started and 1.28% before the bank said in

March that it would buy corporate bonds.

"We're all looking at the data," said the head of credit trading

at a major European bank. "They're only one new customer -- but

it's a big one."

And banks are rushing to serve it. Credit Suisse Group AG

reshuffled its sales coverage of national central banks in recent

weeks when the trading desk realized it wasn't doing enough

business with the new largest buyer in town, according to a person

familiar with the matter.

The ECB's corporate-bond program may well grow further. The bank

is widely expected to extend quantitative easing beyond March, when

it is planned to end. Government bonds are growing increasingly

scarce. The ECB can buy only bonds that yield more than its deposit

rate, currently minus-0.4%. That rules out vast amounts of German

government debt, and much else too.

More corporate bonds are one option, and the central bank could

buy a greater proportion directly from companies. The program has

only been operating in the summer, typically a slow season for bond

sales.

That means more opportunities for investors.

Credit strategists at Citigroup Inc. calculate that bonds

eligible for ECB purchases have outperformed ineligible bonds by

roughly 30% since the program was announced in March.

Tom Ross, a portfolio manager at Henderson Global Investors,

said he spends a good deal of time perusing a spreadsheet created

by his team to track and analyze ECB purchases.

"It has a number of implications," he said. The ECB owning a

bond "is almost like a backstop bid. It provides liquidity in a

time of stress."

--Tom Fairless contributed to this article.

Write to Christopher Whittall at

christopher.whittall@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

August 22, 2016 02:47 ET (06:47 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

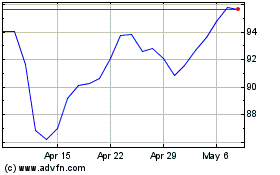

Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

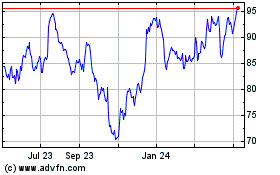

Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024