European central bankers this week began testing how a bank

default would pressure certain trade-plumbing firms, the latest

sign of concern over the clearinghouses that aim to limit markets'

vulnerability to the damaging fire sales that characterized the

2008 crisis.

Stress-testing clearinghouses, alongside a related discussion of

the terms of any public assistance they may receive in a pinch, are

issues at the top of the agenda for many regulators, bankers and

investors, following the adoption of postcrisis rules that placed

these safety nets at the center of financial-system overhauls.

Which conditions might merit public financial assistance is an

issue that the Federal Reserve hasn't taken a public position

on.

The Bank of England along with Germany's Bundesbank and Federal

Financial Supervisory Authority, or BaFin, on Tuesday started to

simulate a hypothetical default by a bank at both the SwapClear

unit of London Stock Exchange Group PLC's LCH.Clearnet Group Ltd.

and Deutsche Bö rse AG's Eurex Clearing, said people familiar with

the test.

The effort comes as investor nervousness about the health of big

banks is on fresh display, with shares of large banks down

significantly this year on both sides of the Atlantic, amid slowing

global growth and falling interest rates. Barclays PLC's

London-listed shares were down 21% this year at midday Thursday,

and Deutsche Bank AG's Frankfurt-listed shares were down 33%.

The exercise is the first example of concurrent stress tests at

two clearinghouses, the people familiar with the event said, and

the first of its kind to be initiated by central banks. Existing

rules dictate the companies must run their own routine stress tests

on an individual basis at least once a year.

Clearinghouses such as LCH and Eurex are supposed to help

prevent a marketwide collapse by ensuring trading partners get paid

even if one defaults. In a 2009 regulatory pact, leaders of the

Group of 20 nations agreed to process hundreds of trillions of

dollars of derivatives through clearinghouses.

Now, analysts are concerned the expanded use of clearinghouses

could magnify the effects of the next crisis. Central bankers have

moved to fortify clearinghouses, taking lessons from bank stress

tests, without committing explicit financial support in advance to

avoid creating a "moral hazard" that analysts warn could cause

excessive risk-taking by clearinghouses. When a clearinghouse runs

into trouble, a primary line of defense is capital from its member

banks.

In the U.S., the question of when the Fed would assist an ailing

clearinghouse is murky and politically charged following the 2008

taxpayer bailout of American International Group Inc.

Wall Street would like clearinghouses to have liquidity from the

U.S. central bank so long as the firms remain solvent, according to

Thomas Kloet, a former chief executive of exchange operator TMX

Group Ltd. and chairman of a subcommittee within the market risk

advisory group at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission.

Emily Portney, a clearing executive with J.P. Morgan Chase &

Co., said at a CFTC committee meeting last year that the reason

banks and other participants are aligned on the issue is because

without dedicated central-bank support "you're actively allocating

liquidity out to banks at the worst possible time."

Last year, the European Central Bank and the Bank of England

announced new measures to enhance the liquidity and stability of

clearinghouses, but said they were extending facilities called

existing swap lines to the firms "without pre-committing to the

provision of liquidity."

In the U.S., the Fed hasn't publicly stated how and when it

would provide liquidity to clearinghouses in stressed periods. The

central bank has authority under the 2010 Dodd-Frank

financial-overhaul law to offer clearinghouses borrowing privileges

"only in unusual or exigent circumstances" so long as certain

requirements are met and firms have tried to borrow privately.

Still, there remains a concern that such assistance could be

viewed as tantamount to a government backstop.

In a November speech, Fed governor Jerome Powell said, "By

design, increased central clearing will concentrate risks in

[clearinghouses]; it is essential that, as these risks accumulate,

[they] build up their ability to manage them."

Last year, regulators at the Fed and the Securities and Exchange

Commission started pushing a large U.S. repo clearinghouse to shore

up its finances with a new $50 billion credit facility provided by

its member banks or other institutions, but met resistance from

smaller industry participants who complained they would have to

leave the market.

Next Wednesday, policy makers and central bankers, including Fed

Vice Chairman Stanley Fischer, will gather in Washington for a

conference about last-resort lending organized by the Committee on

Capital Markets Regulation.

Hal Scott, Nomura professor of international financial systems

at Harvard Law School, said when comparing all last-resort lending

powers across Europe, the U.K., Japan and the U.S., the Fed has

"the weakest of the four," in part because of new restrictions

placed in the postcrisis Dodd-Frank law.

Any expansion of the Fed's lending authority to clearinghouses

"could have much harsher implications for the next financial crisis

than anything they have done in the banking or the securities

industries," said Norbert Michel, a research fellow in financial

regulation at the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think

tank.

AIG had fully repaid the bailout by the end of 2012 and the

government made a $22.7 billion profit. But last year, a court

ruled the government exceeded its authority in completing the 2008

rescue.

At the CFTC hearing last November, Kevin McClear, an executive

at clearinghouse and exchange operator Intercontinental Exchange

Inc., said, "We think the best source to get Treasury liquidity

would be the Fed. We don't want to borrow money, but we think we

should have access to the discount window…only during times of

stress, not as business as usual."

Write to Katy Burne at katy.burne@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

February 04, 2016 16:35 ET (21:35 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

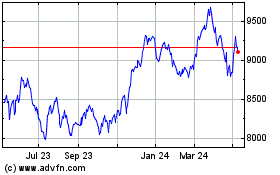

London Stock Exchange (LSE:LSEG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

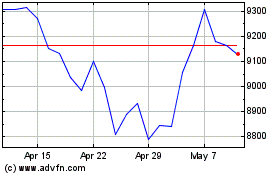

London Stock Exchange (LSE:LSEG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024