RIO DE JANEIRO—For the past two months, Brazilian financial

markets have staged wild rallies over any sign that left-leaning

President Dilma Rousseff might be ousted from office, even as the

nation's economy spiraled further into the depths of its worst

crisis in generations.

Now, with a crucial impeachment vote looming on Sunday,

investors may soon get their wish for new leadership. If two-thirds

of lawmakers in Brazil's lower house vote to try Ms. Rousseff on

charges of doctoring the government's fiscal numbers, she will have

to step aside, at least temporarily.

But while markets are cheering, the prospects for a growth

rebound remain dim, even if Ms. Rousseff is succeeded by a more

business-friendly head of state.

"The economy suffers from a variety of original sins," said Joã

o Pedro Ribeiro, a Brazilian economist at Nomura in New York. He

says Brazil's "potential growth"—how fast gross domestic product is

capable of expanding in the long term—is now "very, very low" in

comparison with other developing countries.

The president's critics say she has mismanaged her nation's

once-flourishing economy and lacks the political skills to push

badly needed overhauls through Congress. Brazil's GDP shrank 3.8%

last year—the biggest contraction in a quarter-century, and a stark

turnaround from the 7.5% growth notched in 2010, the year Ms.

Rousseff was elected.

But the bleeding will likely continue regardless of who Brazil's

president is because the government has virtually exhausted its

firepower to fight the crisis. Years of economic stagnation,

combined with constitutionally mandated spending on things like

health care, education and pensions, have left Brazil's public

sector with a deficit of nearly 11% of GDP.

"We talk about entitlement spending in the U.S., but I mean,

that is what Brazil does—90% of the budget is entitlement spending.

There is no discretionary spending," said Edwin Gutierrez, who

manages $11 billion in emerging-market debt at Aberdeen Asset

Management.

The fixes Brazil needs would require politically unpopular

decisions, such as loosening labor laws and reducing automatic

minimum-wage increases, as public opinion is stacked against

elected officials of all stripes. Ms. Rousseff's likeliest

successor, Vice President Michel Temer, has signaled a pro-market

agenda but will likely have "a very narrow honeymoon" to implement

it, said Christopher Garman, head of country analysis at risk

consultancy Eurasia Group.

A Supreme Court judge recently ordered Brazil's Congress to

charge Mr. Temer with the same offenses it lodged against Ms.

Rousseff. While his chances of impeachment are considered slim

given his strong backing in Congress, sSeveral high-ranking PMDB

members have been implicated in a wide-reaching corruption

scandal.

A newly energized leftist opposition, meanwhile, is likely to

oppose any austerity measures he tries to impose.

"As a result, the binary manner by which markets are treating

this weekend's vote is probably somewhat misplaced," Mr. Garman

said in a research note on Tuesday.

On Monday, for instance, the Brazilian real soared 3% to a

nearly seven-month high against the dollar, even as a survey of

economists by the central bank showed GDP forecasts declining for

the 12th week in a row. The economy is now projected to contract

3.8% in 2016, repeating last year's dismal performance.

Many challenges ahead are enshrined in Brazil's 1988

constitution, which makes it practically impossible for the

government to lay off civil servants and allows workers to start

collecting social security at an average age of 54. The

constitution can be changed only with a two-thirds majority in

Congress.

Another big contributor to the deficit, a law that links minimum

wages and some pensions to inflation, would require a simple

majority in Congress to overturn. But it reflects a practice, known

as indexation, that permeates Brazil's economy, a legacy of the

country's historically high inflation rates.

Such problems, along with other obstacles to growth like

pervasive red tape and poor infrastructure, were masked from 2003

to 2011 by rising prices for Brazil's commodity exports. When

commodity prices began to falter during Ms. Rousseff's first term,

she intervened in the economy with populist policies that

temporarily sustained consumer spending but ultimately left Brazil

with a gaping budget deficit.

Ms. Rousseff attempted to right the fiscal ship after her 2014

re-election by naming a respected banker, Joaquim Levy, as finance

minister with the task of implementing an austerity program. News

of the appointment boosted Brazil's stocks and currency in a

phenomenon that local media called the "Levy effect."

But his most important measures fell flat amid heavy opposition

by interest groups in Congress, and he resigned in December.

Mr. Levy's struggles may bode poorly for Mr. Temer's hopes of

swiftly delivering his party's promise to overhaul the pension

system, cut wasteful government spending and stimulate private

investment.

"We thought when Joaquim Levy came on board…that Brazil was

moving in the right direction," said Michael Henderson, an analyst

at Maplecroft. "But there is a lot of inertia there; a lot of these

structural problems are hard to weed out. There are a lot of vested

interests."

The cautious view of Mr. Henderson and other economists

contrasts with the euphoria that has overtaken Brazil's financial

markets in recent weeks as impeachment proceedings against Ms.

Rousseff picked up speed in Congress.

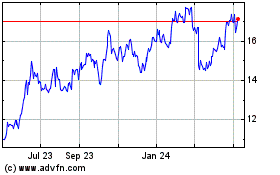

Since mid-February, the benchmark Ibovespa equity index has

soared nearly 30%, and the real has appreciated by about 15%.

Stock-trading volume hit a near-record 8.27 billion reais a day in

March, research firm Economatica said.

Perhaps the best bellwether for investors' sentiment about the

political situation are shares of state oil company Petró leo

Brasileiro SA, which is buried under a mountain of debt and

embroiled in a multibillion-dollar corruption scandal that Ms.

Rousseff's critics blame on her party's interventionist

policies.

Though the company has made scant progress toward solvency and

reported its biggest quarterly loss ever on March 22, Petrobras'

local shares have roughly doubled in the past two months. Investors

are betting that Ms. Rousseff's eventual successor will open up

Brazil's oil sector and allow Petrobras to operate more like a

private company.

Neil Shearing, chief emerging-markets economist at Capital

Economics in New York, says it is possible that a market-friendly

regime could emerge when the dust settles.

"But the groundswell of public discontent against the entire

political class in Brazil may well prove to be a breeding ground

for a more populist movement to come to the fore," Mr. Shearing

said. "In the current environment, what comes after Dilma is highly

uncertain."

Write to Paul Kiernan at paul.kiernan@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 13, 2016 13:45 ET (17:45 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

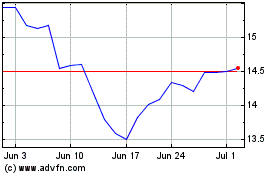

Petroleo Brasileiro ADR (NYSE:PBR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Petroleo Brasileiro ADR (NYSE:PBR)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024