Moving large bundles of shares has become a brisk business for

deal-starved banks

By Maureen Farrell, Corrie Driebusch and Matt Jarzemsky

Just before the Thanksgiving holiday, Morgan Stanley bought

about 3 million shares of insurer James River Group Holdings Ltd.

from hedge fund D.E. Shaw Group. Its intention was to resell the

shares at a profit before the market opened the next day.

It is unclear exactly how Morgan Stanley did on the roughly $117

million purchase. It stood to make $1 on every share it sold on to

investors, Dealogic estimates, but it isn't known how many it

unloaded.

The so-called block trade drew attention on Wall Street, not

because of the potential profit but because the number of shares

was equivalent to more than 30 days of average trading volume in

James River stock. In a typical year, traders say, a bank would

rarely buy more than 10 or 20 days' worth of shares, mindful of the

risk of being unable to unload them without sustaining a loss.

But it's far from a normal year, and Morgan Stanley isn't alone

in taking a more aggressive approach to block trades.

A stalled IPO market has left banks across Wall Street to fight

for the deals, which carry lower margins and higher risk than other

share sales that form the heart of the equity-capital-markets

business.

This year is now the biggest year ever for block-trading

activity, with more than $85 billion worth of U.S.-listed shares

sold, according to Dealogic. In all of 2015, the previous record

year, there were about $62 billion worth of shares sold.

Meanwhile, 2016 is on track to be the slowest for U.S.-listed

initial public offerings in 13 years amid factors including a

proliferation of attractive private-funding options.

Banks have traditionally served as middlemen in stock offerings,

a lucrative assignment in which they line up buyers to purchase

shares directly from companies. In contrast, with a block trade, a

bank buys stock from a public company or one of its big investors

at a discount and then tries to flip it at a profit. If the share

price falls before it can move the stock, however, the bank faces a

possible loss. That makes block trading a riskier proposition for

banks than traditional underwriting.

It's no mystery why stock sellers like this approach: They are

guaranteed a set price, and if the shares subsequently fall, they

don't take the hit.

There was $11.6 billion in stock sold in the U.S. through block

trades in November, according to Dealogic. That makes it the third

busiest month on record, behind this August and March of last year,

which was No. 1.

The rise of block trading has led to big changes in how

companies and investors approach stock sales.

"Sellers' attitudes and preferences have changed. They want

price certainty and minimal market risk," said Felipe Portillo,

managing director of equity-capital-market syndicate at Credit

Suisse Group AG. "Buyers have also learned to be ready and are

comfortable making quick investment decisions."

The surge in block trades has dealt a blow to

equity-capital-markets desks across Wall Street. Fees in the U.S.

are on pace to hit a low of 20-plus years in 2016, according to

Dealogic. Through Dec. 1, banks had generated $4.9 billion in

equity-capital-markets fees this year, down 34% from the same time

last year. Block trades accounted for roughly 42% of the business,

the largest share ever by a wide margin.

And the field is becoming more competitive, which in some cases

has prompted banks to take on more risk facilitating the deals. As

block trades become more popular, banks sometimes find themselves

in bidding wars to win deals. Before the financial crisis, only a

handful of banks participated in the deals, but now smaller players

are getting in on the action too. In November, midsize Chicago bank

William Blair & Co. led its first block deal since 2003,

according to Dealogic.

Citigroup Inc. has typically been one of the biggest players in

block trades, executing more than $46 billion worth between the

start of 2011 and the end of 2015, according to Dealogic. So far

this year, the bank has facilitated roughly $8 billion in block

deals, placing it in sixth, according to Dealogic. Goldman Sachs

Group Inc. and J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. are first and second

this year, underwriting $16.5 billion and $15 billion,

respectively, in U.S.-listed block trades.

Rising stocks have helped banks unload recent blocks at a

profit, and there are scant examples of big losses. But that could

quickly change recent market gains reverse, which in turn could

dampen enthusiasm by banks to bid on deals, analysts say.

Indeed, behind many of the recent deals are private-equity firms

cashing out. The flood of selling by sophisticated investors could

be a sign of a market top -- though such firms do face pressure to

exit investments and return cash to their backers.

In November alone, KKR & Co. sold its remaining $1.67

billion stake in drugstore chain Walgreens Boots Alliance Inc. and

Blackstone Group LP sold shares of Summit Materials Inc., Hilton

Worldwide Holdings Inc., Extended Stay America Inc., Performance

Food Group Co. and Hudson Pacific Properties Inc.

Also, if the IPO market returns to more normal levels next year,

as is widely expected, block-trading volume could decline somewhat,

bankers say.

"As IPO volume picks up, people will become more rational," said

Mr. Portillo of Credit Suisse.

Write to Maureen Farrell at maureen.farrell@wsj.com, Corrie

Driebusch at corrie.driebusch@wsj.com and Matt Jarzemsky at

matthew.jarzemsky@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

December 07, 2016 02:48 ET (07:48 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

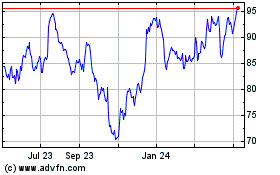

Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

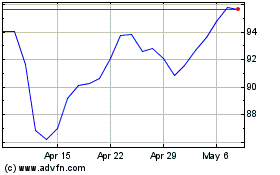

Morgan Stanley (NYSE:MS)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024