By Rachel Louise Ensign and Liz Hoffman

Bank of America Corp. is the stingiest of the big, U.S. banks.

But its depositors don't seem to care.

Last year, the bank paid an average of 0.08% for its

interest-bearing deposits in the U.S. That was around half the rate

paid by J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. or Wells Fargo & Co. and a

fraction of what firms such as Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Ally

Financial Inc. paid.

Yet Bank of America kept raking in customers' money. Such

deposits increased $33 billion over 2015.

Bank of America's ability to keep paying next to nothing

highlights the built-in advantages of big banks as well as changes

in consumer attitudes toward deposits. For investors, it indicates

some banks may be able to raise rates more slowly than in past

Federal Reserve rate-hiking cycles, bolstering profits.

Indeed, Bank of America's low deposit costs helped boost its

profit margins and played a part in pushing the bank to a 40%

first-quarter profit increase from a year earlier.

While the Federal Reserve raised rates again in the quarter, the

trend didn't change for Bank of America. Its average cost of U.S.,

interest-bearing deposits was just 0.09% and deposits in its

consumer-banking business increased by a further $29 billion from

the fourth quarter, according to the bank's quarterly earnings

presentation.

By holding the line on deposits, Bank of America gains a

competitive advantage. Consider that it paid $617 million for about

$796 billion in U.S., interest-bearing deposits in 2016, according

to bank regulatory filings, far less than what J.P. Morgan and

Wells Fargo paid for only a bit more in funds.

And Bank of America's interest payout came in below Goldman's

$828 million expense or the $822 million Ally forked out -- even

though those banks have just $115 billion and $79 billion of

deposits, respectively.

Consumers clearly could make more by putting their money

elsewhere. Had Bank of America customers moved all their money to

J.P. Morgan, they would have made $700 million more at its average

deposit-cost rate. Move it all to Goldman and they would have

pocketed $5.1 billion more.

That they haven't moved money elsewhere speaks to the stickiness

of deposits. It also bolsters a central argument by banks in the

face of calls they should be broken up: Customers value their

breadth and the different services they offer.

Bank of America, for example, had 4,559 branches in the U.S. and

15,939 ATMs at the end of the first quarter. Goldman Sachs Bank

USA, on the other hand, has no ATMs and retail customers can't walk

into a Goldman branch.

Indeed, depositors place a premium on convenience, like being

able to access thousands of ATMs or transfer money using their

smartphones.

Abby Trexler of New York has kept savings and checking accounts

at J.P. Morgan Chase for more than a decade and says she has no

plans to move them to a higher-yielding account. A number of years

ago, she had an account with an online bank and found it cumbersome

to get money in and out.

Ms. Trexler, who is in her mid-30s and works in communications,

likes Chase's ubiquitous ATMs and mobile technology. For instance,

she and her sisters used the bank's payments feature to split the

cost of their parents' Christmas gifts last year.

"There are people like me willing to give up a little bit," Ms.

Trexler said. "It just seems like such a hassle to not be able to

walk in on every corner and get done what I need to get done."

Younger consumers also prefer the largest U.S. banks because

they think their technology is better, said Jim Miller, senior

director at market-research firm J.D. Power. Customers under 40

give the bigger banks higher satisfaction marks for things like

mobile banking. This age group is particularly important to keep

happy because they are five times more likely to switch banks than

older customers, according to J.D. Power research.

Another factor working in the big banks' favor: They serve a lot

of depositors with small accounts. For those savers, gains from

switching to a higher-yielding account typically aren't worth the

hassle, especially in an age of superlow rates.

Say a depositor has $3,000 in a standard Bank of America savings

account. On the face of it, that person could gain a lot by moving

from such an account, which typically pays about 0.01%, to GS Bank,

which offers a savings account with a 1.05% yield.

The practical impact is far smaller: the gain, over a year, from

switching would only be around $31.

In the face of that, many bank customers, especially younger

ones, have stopped shopping around for deposit rates as they did

before the Fed took rates to near-zero levels.

"They don't even think about interest rates for deposits because

it's never been anything they could make any money off of," said

J.D. Power's Mr. Miller. Even including the higher-rate offers from

banks like Goldman Sachs, "the rates are so low that you almost

think of it as no rate at all."

Write to Rachel Louise Ensign at rachel.ensign@wsj.com and Liz

Hoffman at liz.hoffman@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 08, 2017 05:44 ET (09:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2017 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

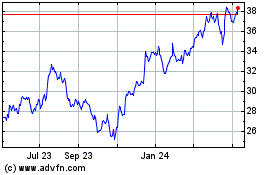

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

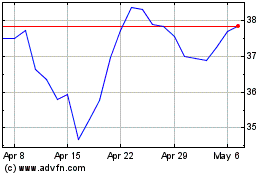

Bank of America (NYSE:BAC)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024