President Brad Smith on why the company has sued the feds four

times in three years

By Jay Greene

REDMOND, Wash. -- Companies often try to steer clear of

conflicts with the government. But Microsoft Corp. is picking

fights with the government.

In the past three years, the software giant has sued the federal

government four times, challenging law-enforcement efforts to

secretly search customer data on servers at Microsoft's data

centers in the U.S. and elsewhere. Microsoft, like several other

tech companies, often receives federal demands for customer

information, such as emails, that include gag orders barring the

company from telling those customers the government looked at their

data.

Microsoft's most recent suit, filed in April against the Justice

Department, contests the constitutionality of preventing tech firms

from telling customers when federal agents have examined their

digital files.

Like Apple Inc. and Alphabet Inc., which have challenged the

government over similar issues, Microsoft has been hailed by

privacy activists and civil libertarians worried about government

overreach. The company has also faced criticism from law

enforcement that its actions could hamper criminal

investigations.

Microsoft's president and chief legal officer, Brad Smith, is

the architect of the company's strategy to challenge the

government. Mr. Smith, who says he recognizes the importance of

government investigations, believes that indefinite gag orders

violate Microsoft's First Amendment right to inform customers about

searches of their files, and that secret searches violate the

Fourth Amendment requirement that the government give notice to

people when their property is being searched or seized.

The Wall Street Journal talked with Mr. Smith in his office at

Microsoft headquarters here about the company's strategy, and its

attempt to balance concerns about public safety with the desire to

protect customer privacy. Edited excerpts follow.

What's at stake?

WSJ: Microsoft has sued the federal government four times in the

past three years. Why?

MR. SMITH: These suits have all involved situations where we've

felt that the company's business and the interests of our customers

were at stake around security and privacy. They also involved

important issues of principle, including the right of people to

know what the government is doing in certain circumstances.

WSJ: Tell me about the decision-making process at Microsoft to

file the suits.

MR. SMITH: Before filing the lawsuit [in April], I shared the

thinking with three groups of people. First and foremost, Satya

Nadella, our CEO; our senior leadership team that meets every

Friday for half a day; and our board of directors. I made sure

people knew what our thinking was, what we were planning to do, and

welcomed feedback. In each case, everybody expressed a substantial

level of comfort and understanding with what we were doing.

It's important for us to use a blog to communicate externally

and internally. Our employees are going to find themselves needing

to make similar decisions in the future, or explaining these

decisions to our stakeholders, including our customers. We [also]

need to get our rationale down to 122 characters so it can be put

in a tweet that can be retweeted. The very last step is sitting

down and asking, "What is the heart and soul of what we're trying

to communicate? How do we get this down to 122 characters so we can

really explain it to the world?"

WSJ: Did anyone in the leadership say, "This is a step too

far?"

MR. SMITH: There wasn't a voice to that effect. In the most

recent case, we concluded that we were basically being left with no

choice. One of the challenges with these secrecy orders is that

they were being pursued across the country by 93 different U.S.

attorney's offices that, to a certain degree, make decisions in a

fragmented way. So we were constantly trying to hammer things out

with office after office and, not surprisingly when you have 93

different offices, eventually you start to encounter situations

where things break down.

These are issues we had tried to raise with the Justice

Department in Washington, D.C., over the last few years. They work

in an environment that has so many competing priorities that many

days we would find that our concerns just didn't make it high

enough on their list for effective action to be taken.

Consumer reaction

WSJ: Have you polled consumers on this issue?

MR. SMITH: We definitely have. We've done I would say on average

one or two consumer-oriented polls each year over the last few

years, since these issues first arose. And if there is a constant

point of almost universal consensus among the American public, it's

this: People feel fundamentally comfortable with the balance of

governmental power and individual rights that has existed in the

U.S. since the country was founded and information was put on

paper. And what people want is to see information that is stored

digitally in the cloud get the same kind of protection as

information that is written down and stored on paper.

WSJ: Some police groups came out against Microsoft. Are there

dangers from a public perception standpoint?

MR. SMITH: One needs to be prepared to accept some level of risk

to accomplish anything of significance. It behooves us to

communicate carefully. It's always important for us to acknowledge

that some of these issues involve competing values that are each

important in their own right. This isn't a battle of good versus

evil as much as it involves thinking through how we as a society

move to the cloud in a way that keeps our traditional values

intact.

Typically, ultimately, some middle ground needs to emerge. While

debates can start with two opposing people, they typically end with

a handshake.

WSJ: How did Microsoft work with law enforcement after the Paris

attacks?

MR. SMITH: Even while we fervently believe in privacy and are

prepared to go to court to disagree with our own government, we do

recognize that our industry has not only a role but a

responsibility to help keep the public safe.

In the wake of the Paris attacks last November, we did receive

14 lawful orders from the police in Paris and Brussels. And in all

14, we concluded they were lawful orders. We concluded that we had

the information the government was requesting and could turn it

over. And, in fact, we did turn it over with an average turnaround

time of under 30 minutes. There are days when people's lives are at

stake. And on those days it is our job to work hard to serve the

public in this broad way.

Mr. Greene is a reporter for The Wall Street Journal based in

Seattle. He can be reached at jay.greene@wsj.com.

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

May 31, 2016 02:51 ET (06:51 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

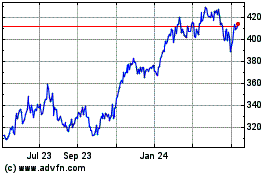

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

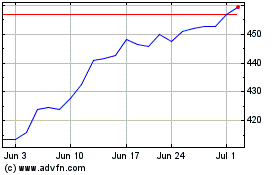

Microsoft (NASDAQ:MSFT)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024