Need For Welders Belies Decline in U.S. Manufacturing Jobs

November 23 2009 - 4:38PM

Dow Jones News

The unraveling of U.S. manufacturing employment in the past year

hasn't damped the outlook for welders, whose numbers lag far below

the projected work force needed for increased spending on public

infrastructure and energy projects.

As many as 200,000 additional welders will be needed by 2014, a

40% increase over the current number of welders in the U.S.,

according to industry estimates. Trade schools and training

programs turn out about 25,000 new welders a year, but twice as

many welders leave the trade annually, mostly because of

retirement.

Despite the loss of 1.5 million manufacturing jobs in the past

year, or about a 12% reduction in the total U.S. manufacturing work

force, employers complain that they can't find enough trained

welders. The shortage has prompted some equipment manufacturers to

design welding gear with less-accomplished welders in mind.

"There's truly a talent mismatch," said Jonas Prising, Americas

president for job placement service Manpower Inc. (MAN) "There are

lots of people who are unemployed who'd like to apply for these

welding jobs, but they don't have the skills."

It is a problem that isn't limited to welding. Openings for

machinists and other manual skilled trade workers have been among

the hardest jobs to fill in recent years, according to

Manpower.

As high school shop classes and other vocational career programs

have been pared back in the past 20 years in favor of more college

preparatory curriculums and technology-related courses, teen-agers

have had less exposure to skilled trades.

Parents, many of whom now work in service-sector jobs

themselves, also are reluctant to encourage their children to

pursue skilled trades, fearing that such jobs will disappear like

millions of other manufacturing jobs draining out of the U.S

economy.

Experts say welding, in particular, is often perceived as a

dying occupation being replaced by robot welders in factories or

outsourced to low-wage workers overseas.

"I'll have parents say that robots are taking the jobs away from

welders, but we need welders to run the robots," said David Cotner,

welding department head for the Pennsylvania College of Technology

in Williamsport. "They're the ones who make sure that the robots

are running optimally. It's taken people time to see that welding

isn't just dirty, blacksmith-type work."

Observers say enrollment in training programs is up across the

country as recently displaced workers look for other careers.

Starting pay for newly trained welders is about $36,000 a year and

experienced welders can earn double that amount.

Nevertheless, the flow of new workers into the trade isn't

expected to match the amount of welding work anticipated in the

coming years as bridge structures, transit systems, water plants

and other public infrastructure undergo repairs or replacement.

The American Society of Civil Engineers projected earlier this

year that $2.2 trillion needs to be spent on the aging

infrastructure in the U.S. in the next five years just to keep it

in adequate condition. The U.S. economic stimulus legislation

included about $100 billion for infrastructure improvements.

Meanwhile, the resurgent nuclear-power industry, the

construction of wind-energy turbines and elevated investment in oil

and natural gas pipelines are creating more jobs for welders in the

energy sector.

"We've got to bring more talent into the business. I don't think

there's a single welder coming out of our school who can't get a

job," said Carl Peters, director of training for Cleveland-based

Lincoln Electric Co. (LECO), which has operated its own welding

school since 1917. Lincoln, the world's largest seller of cutting

and welding equipment, this autumn started marketing a

virtual-reality welding simulator to lower schools' costs for

training welders.

The simulator sells for about $46,000, but doesn't consume

fluxes or electrodes and requires less instructor supervision than

an actual electric-welding machine. The simulator provides

computer-generated images to give students experience in applying

molten metal to metal joints.

Other equipment manufactures are adjusting their product lines

to accommodate the shortage of welders. Miller Electric

Manufacturing Co., a unit of industrial conglomerate Illinois Tool

Works Inc. (ITW), has redesigned its welders and simplified the

controls for workers with minimal instruction in welding.

"We understand what the customers' pains are," said Mike Weller,

North American welding president for Wisconsin-based Miller

Electric. "You have a less-trained welder today than ever

before."

-By Bob Tita, Dow Jones Newswires; 312-750-4129;

robert.tita@dowjones.com

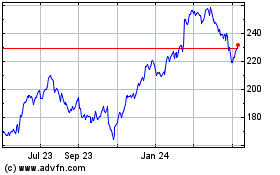

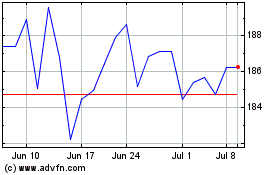

Lincoln Electric (NASDAQ:LECO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

Lincoln Electric (NASDAQ:LECO)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024