By Eliot Brown

Google parent Alphabet Inc. has legions of web developers. Soon

it might be in need of real-estate developers.

In coming weeks, top executives at the Mountain View, Calif.,

technology giant are set to weigh a pitch from Alphabet's urban

technology-focused subsidiary, Sidewalk Labs, on a plan to delve

into an ambitious new arena: city building.

According to people familiar with Sidewalk's plans, the division

of Alphabet is putting the final touches on a proposal to get into

the business of developing giant new districts of housing, offices

and retail within existing cities.

The company would seek cities with large swaths of land they

want redeveloped -- likely economically struggling municipalities

grappling with decay -- perhaps through a bidding process, the

people said. Sidewalk would partner with one or more of those

cities to build up the districts, which are envisioned to hold tens

of thousands of residents and employees, and to be heavily

integrated with technology.

The aim is to create proving grounds for cities of the future,

providing a demonstration area for ideas ranging from self-driving

cars to more efficient infrastructure for electricity and water

delivery, these people said.

Details on the effort, which was reported earlier this month by

the technology news website the Information, are scant. Most

important, it is unclear who would cover the cost of such an

endeavor -- tens of billions of dollars -- since large-scale

development typically requires buy-in by third-party investors over

a period of years or decades.

But one key element is that Sidewalk would be seeking autonomy

from many city regulations, so it could build without constraints

that come with things like parking or street design or utilities,

the people said.

If Alphabet greenlights the project, it would be in the same

category of unlikely-but-promising moon-shot investments as its

self-driving car division.

Sidewalk was formed last year, the brainchild of Alphabet Chief

Executive Larry Page and Sidewalk CEO Daniel Doctoroff, New York

City's economic development czar during the first six years of the

administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg. There Mr. Doctoroff was

known for a technocratic approach to government and large ambitions

for development, many of which involved converting formerly

industrial parts of Manhattan and Brooklyn into neighborhoods where

office and apartment towers have sprouted like mushrooms in the

past decade.

Mr. Doctoroff went on to run Mr. Bloomberg's media company,

Bloomberg LP, and last year started Sidewalk, describing it as a

company that would use technology to help transform cities.

In recent months, Mr. Doctoroff and a flock of consultants and

staff, including several of his former deputies at City Hall, have

been racing to put together their game plan for the city-building

initiative, people who have spoken to Mr. Doctoroff said.

He hinted at his ambitions in a February speech at New York

University.

"What would you do if you could actually create a city from

scratch," he said. "How would you think about the technological

foundations?"

Past efforts to build "smart" cities or districts integrated

with technology have failed, he said, because typically urban

planners and tech executives don't understand each other.

"That is why the combination of Google, which focuses on the

technology, and, me, who focuses on quality of life, urbanity,

etc., we think is a relatively unique combination," he said.

One challenge the company would face would be that the history

of city-building and large-scale urban development projects is full

of failures and disappointments. Cities built from scratch, like

Brasília or Canberra, Australia, are viewed as antiseptic and

without the vibrancy of more organic cities.

"You can build a city from scratch and you can copy and emulate

the great qualities of cities," said Glen Kuecker, a history

professor at DePauw University who has studied the Songdo City

district near Seoul and other smart cities. "It's still a very

artificial and sterile place."

Large-scale development projects within cities, too, are often

marked by frequent delay and failure. Battery Park City, a

development in lower Manhattan, took four decades and a

near-bankruptcy to be completed, as did the Playa Vista district of

Los Angeles, north of the airport.

This is because developers aren't only facing swings of the

market, but also of political dynamics that change frequently.

"You've got political barriers, you've got economic barriers,

sometimes you've got environmental barriers," said Eugenie Birch, a

city planning professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

Mr. Doctoroff ran into many of these headwinds in his tenure in

New York, where he gathered together countless ideas that had been

collecting dust on planners' shelves and tried to put them into

action.

"He dares to dream big -- he's always pushing to do the next big

thing," said Robert Lieber, who worked under Mr. Doctoroff in New

York City government before succeeding him as deputy mayor.

Many of these ideas were successful, including his rezoning of

Manhattan's far West Side, which today is becoming an office

district serviced by a brand new subway extension, as well as

multiple rezonings in Brooklyn that have spurred thousands of units

of new housing.

One of his weaknesses, people who know him say, was legislative

politics, at least in New York State government. His two

highest-profile plans -- a stadium for the city's 2012 bid for the

Olympic Games and a congestion-pricing charge on drivers in

Manhattan -- were both defeated by the state legislature.

Write to Eliot Brown at eliot.brown@wsj.com

(END) Dow Jones Newswires

April 26, 2016 12:44 ET (16:44 GMT)

Copyright (c) 2016 Dow Jones & Company, Inc.

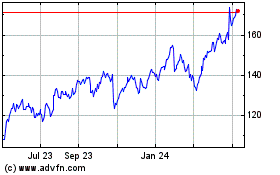

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Mar 2024 to Apr 2024

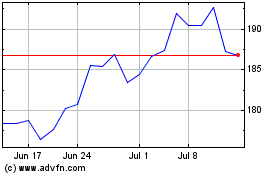

Alphabet (NASDAQ:GOOG)

Historical Stock Chart

From Apr 2023 to Apr 2024